Search Results for Tag: ice

Polar melt confirmed from space

I am disappointed that there was so little mainstream media coverage (please correct me if I am wrong) of a report from a team of scientists from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in Bremerhaven who have analysed just over two years of data from the CryoSat-2 satellite. Their conclusion that the Greenland ice sheet and Antarctica’s glaciers are melting at record pace, dumping some 500 cubic kilometers of ice into the oceans every year, twice as much in the case of Greenland and three times as much in the case of Antarctica, by comparison with 2009 – yes, you read right, we are talking about a very short period for such a dramatic increase in ice loss – should have made more news headlines and not just the science pages.

To understand the scale of that, the researchers say it would be the equivalent of an ice sheet that’s 600 meters thick and covers an area as big as the German city of Hamburg – or, my colleagues here at DW calculate, as big as Singapore.

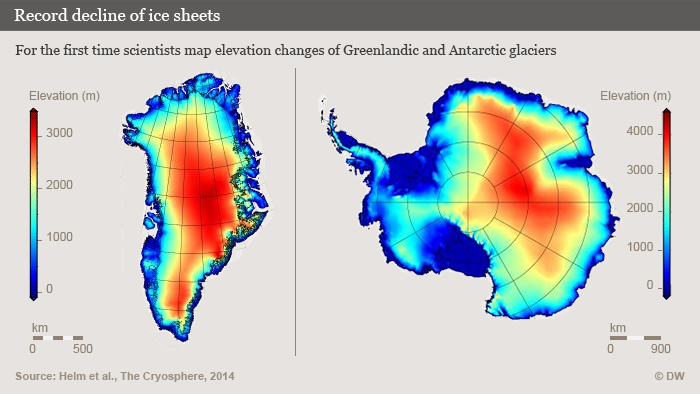

The research team headed by Veit Helm used around two years’ worth of data from the ESA CryoSat-2 satellite to create digital elevation models of Greenland and Antarctica. The results were published in the online magazine of the European Geoscience Union (EGU) The Cryosphere.

“The new elevation maps are snapshots of the current state of the ice sheets,” Helm says. “The elevations are very accurate, to just a few meters in height, and cover close to 16 million square kilometers of the area of the ice sheets.” He says this includes an additional 500,000 square kilometers that weren’t covered in previous elevation models from altimetry.

Space technology shows declining ice mass

Helm and his team analyzed all data from the CryoSat-2 radar altimeter SIRAL in order to come up with the detailed maps. The satellite with this new radar equipment was launched in 2010. Satellite altimeters measure the height of an ice sheet by sending radar or laser pulses which are then reflected by the surface of the glaciers or surrounding areas of water and recorded by the satellite.

The researchers used other satellite data as well to document how elevation has changed between 2011 and 2014.

Rapid ice loss over a short period of time

The team used more than 200 million SIRAL data points for Antarctica and some 14 million data points for Greenland to create the elevation maps. The results show that Greenland alone is losing around 375 cubic kilometers of ice per year.

Compared to data which was collected in 2009, the loss of mass from the Greenland ice sheet has doubled. The rate of ice discharge from the West Antarctic ice sheet tripled during the same period.

I think this is definitely worth talking about. We know the huge implications of polar ice melt for global sea levels. Other research from this year also tells us that, at least in the case of parts of Antarctica, the ice melt is probably irreversible.

We cannot afford to ignore what is happening to the ice sheets. The extent of ice loss in Greenland is particularly dramatic. I am losing patience with those people who respond to studies like this and our reporting on it by saying “but the East Antarctic is gaining volume” and “the Antarctic sea ice has grown”. It is so easy to take things out of context and mix different factors up when trying to understand a very complex system.

I will give the last word here to AWI glaciologist Angelika Humbert, who co-authored the study: “If you combine the two ice sheets (Greenland and Antarctic), they are thinning at a rate of 500 cubic kilometers per year. That is the highest rate observed since altimetry satellite records began about 20 years ago.” It seems to me there is no arguing with that.

Related stories:

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable

Climate change risk to icy East Antarctica

Antarctic Glacier’s retreat unstoppable

Human action speeds glacial melting

It might sound like stating the obvious, but in fact it is not easy to find clear evidence that human behavior is behind the retreat of glaciers being monitored in different parts of the world. Hence my interest in a study just published in the journal Science.

The main problem is that it usually takes decades or even centuries for glaciers to adjust to climate change, says climate researcher Ben Marzeion from the Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics of the University of Innsbruck. He and his team of researchers have just published the results of a study for which they simulated glacier changes during the period from 1851 to 2010 in a model of glacier evolution. They used the recently established “Randolph Glacier Inventory” (RGI) of almost all glaciers worldwide to run the model, which included all glaciers outside Antarctica.

“Melting glaciers are an icon of anthropogenic climate change”, the authors say. However, they stress that the present-day glacier retreat is a mixed response to past and current natural climate variability and “current anthropogenic forcing”. Their modeling shows though that whereas only 25% of global glacier mass loss between 1851 and 2010 can be attributed to human-related causes, the fraction increases to around 69% looking at the period between 1991 and 2010. So human contribution to glacier mass loss is on the increase, the experts write.

Marzeion says the global retreat of glaciers observed today started around the middle of the 19th century at the end of the Little Ice Age, responding both to naturally caused climate change of past centuries (like solar variability), and to human-induced changes. Until now, the real extent of human contribution was unclear. The authors say their latest piece of work provides clear evidence of the human contribution.

Once more I am happy to refer to the Climate News Network, in this case to Tim Radford, for an easy-to-read summary of the main research results and the background. There is no doubt that glaciers are losing mass, retreating uphill and melting at a faster rate, says Radford. He refers to some Andes glaciers and the the Jakobshavn glacier in Greenland, or Sermeq Kujualleq as I prefer to call it, using the indigenous name. Ice Blog followers may remember my own trip to Greenland and that particular glacier. I have also written on the speeding of the melt there on the Ice Blog and on the DW website.

Alpine glacier like these in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, have declined dramatically in recent decades. (I.Quaile)

Radford also refers to ascertaining the melting of alpine glaciers by comparing historic paintings and other documentation with the current ice mass. That decline is something I have observed at first hand in Valais in Switzerland during regular visits over the past 30 years. Look out for a comparative photo gallery of my own pics, when I get time to put it together. Since most of the shots are from the pre-digital era, that will be a time-consuming task.

I also remember a trip to the Visitor Centre of the Begich Boggs glacier in Alaska in 2008. The glacier has already retreated so far you can’t see it at all from the Centre built specially for the purpose of viewing it.

The question until now was how much of all this was caused by natural developments and how much to changes in land use and the emission of greenhouse gases? The latest study supported, among others, by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and the research area Scientific Computing at the University of Innsbruck, has come up with some answers. Since the climate researchers were able to include different factors contributing to climate change in their model, they can differentiate between natural and anthropogenic influences on glacier mass loss

“While we keep factors such as solar variability and volcanic eruptions unchanged, we are able to modify land use changes and greenhouse gas emissions in our models,” says Ben Marzeion, who sums up the study: “In our data we find unambiguous evidence of anthropogenic contribution to glacier mass loss.”

As always, there is still need for further research – and a lot more monitoring. The scientists say the current observation data is insufficient in general to derive any clear results for specific regions, even though anthropogenic influence is detectable in a few regions such as North America and the Alps, where glaciers changes are particularly well documented.

With global glacier retreat contributing to rising sea-levels, changing seasonal water availability and increasing geo-hazards, the study’s conclusions should help put a little more pressure on the world’s decision-makers to get serious about emissions reductions.

Arctic thaw – carry on regardless?

When a colleague who has a lot of sympathy for those who do NOT accept that humans are responsible for global warming drew attention to the fact that this had been the hottest June on record, following hard on the hottest May, I must admit I was temporarily put of my guard. Aha, I thought. Is he finally getting the message? Alas, the answer is no. There is a small minority of people that still argues – for whatever reason – that natural variation could be responsible for all this, while acknowledging the record concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere. “And all that stuff”. Hm.

![]() read more

read more

World Cup Champs for Arctic Climate?

Chancellor Merkel is on her way from the World Cup Final in Brazil to Berlin, where she will address the Petersberg Climate Dialogue. This is an informal but influential meeting of 35 international ministers, co-chaired by Peru, the host of the next world climate conference this December. UNFCCC chief Figueres is also in attendance, hoping progress will be made towards a successful Peru conference and a new world climate agreement to be signed in Paris in 2015. Yes, it is a kind of conference to prepare the conference to prepare the conference…. but every little step helps. As I wrote here and on the DW website during the last round of preparatory talks in Bonn, things are looking more positive than they once did, with the big players USA and China finally coming into the game. Here’s hoping Frau Merkel can bring some of the energy and enthusiasm from the World Cup into the “Petersberg Dialogue” (initiated on the Petersberg here in Bonn, but since moved to Berlin) and the climate process. I interviewed Martin Kaiser, the climate policy chief at Greenpeace about the current state of play. You can read the interview here. But I also talked to him about that key ice blog issue, the relevance of all this to the Arctic.

Here is his response, if you would like to listen: For those who prefer a read, this is what Martin Kaiser had to say about the UN climate process and the Arctic:

“If we want to limit the ice melt in the Arctic, we have to address the issue of climate change. If we don’t manage to get countries like China and the US, to drastically reduce emissions from burning coal and oil, the ice melt is unstoppable. The Arctic is one of the places in the world where you can see the drastic changes caused by global warming in a most visible way. We expect a historic minimum ice melt this September, and this will give a clear warning when heads of state are going to meet in New York at around the same time.

It’s quite contradictory that oil companies are going to the Arctic to drill for more fossil energy which will fuel global warming even more. This needs to stop. That’s why Greenpeace is calling for a sanctuary in the Arctic which prohibits commercial exploitation of the region.

(Ice Blogger: How does that look in the countries with Arctic regions?)

If we look at Canada – It has one of the most regressive climate policies in place, Prime minister Harper is one of the worst climate deniers, and Canada is investing a lot into tar sands in the west of the country – a business model that is not sustainable. Russia’s business model is based on the export of oil and gas, so it is problematic to talk to Russia about the protection of the Arctic at the moment. Greenpeace has had experience of how they prioritize this business model over preserving the rare ecosystem. There are more countries like China and India coming in to the Arctic, and wanting to get a share of the resources extraction, and that is a worrying sign. Instead of protecting the Arctic, it’s opening like the Wild North for the big corporates investing into oil and gas. That means we have to have a political process which clearly determines a sanctuary in the Arctic and limits commercial exploitation of it.

Finland has been quite progressive so far to move forward the idea of a sanctuary in the Arctic. We hope that rich countries like Norway or also Iceland will join that group. But that’s a long way to go.”

Keeping Greenland in focus

Two interesting publications relating to Greenland caught my eye over the past few days. But it has not proved easy to get them onto the international news agenda. Given the huge importance of the Greenland ice sheet to the planet’s future, this is frustrating to say the least. Fortunately there is the Ice Blog.

The first research relates to a study about the role of ash from fires in bringing about large-scale surface melting. The other predicts Greenland will be a far greater contributor to sea rise than expected.

Let me start with the latter, published in Nature Geoscience. Scientists from the University of California – Irvine and NASA glaciologists have found previously uncharted long deep valleys under the Greenland Ice Sheet. Since these bedrock canyons are well below sea level, they are much more vulnerable to warm ocean waters than previously thought. When warmer Atlantic water hits the fronts of hundreds of glaciers, the edges will erode much further than previously assumed, releasing far greater amounts of water.

Ice melt from the subcontinent has already accelerated, as warmer marine currents have migrated north, the authors say. Older models predicted that once higher ground was reached in a few years, the ocean-induced melting would halt. Greenland’s frozen mass would stop shrinking, and its effect on higher sea waters would be curtailed.

“That turns out to be incorrect. The glaciers of Greenland are likely to retreat faster and farther inland than anticipated – and for much longer – according to this very different topography we’ve discovered beneath the ice,” says lead author Mathieu Morlighem, a UC Irvine associate project scientist, on the university website. “This has major implications, because the glacier melt will contribute much more to rising seas around the globe.”

To obtain the results, Morlighem developed what he says is a breakthrough method that for the first time offers a comprehensive view of Greenland’s entire periphery. It’s nearly impossible to accurately survey at ground level the subcontinent’s rugged, rocky subsurface, which descends as much as 3 miles beneath the thick ice cap.

Since the 1970s, limited ice thickness data has been collected via radar pinging of the boundary between the ice and the bedrock. Along the coastline, though, rough surface ice and pockets of water cluttered the radar sounding, so large swaths of the bed remained invisible.

Measurements of Greenland’s topography have tripled since 2009, thanks to NASA Operation IceBridge flights. But Morlighem says he quickly realized that while that data provided a fuller picture than the earlier radar readings, there were still major gaps between the flight lines.

To reveal the full subterranean landscape, he designed a novel “mass conservation algorithm” that combined the previous ice thickness measurements with information on the velocity and direction of its movement and estimates of snowfall and surface melt.

The difference was dramatic, says Morlighem. What appeared to be shallow glaciers at the very edges of Greenland are actually long, deep fingers stretching more than 100 kilometers (almost 65 miles) inland.

“We anticipate that these results will have a profound and transforming impact on computer models of ice sheet evolution in Greenland in a warming climate,” the researchers conclude.

“Operation IceBridge vastly improved our knowledge of bed topography beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet,” said co-author Eric Rignot of UC Irvine and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “This new study takes a quantum leap at filling the remaining, critical data gaps on the map.”

Other co-authors are Jeremie Mouginot of UC Irvine and Helene Seroussi and Eric Larour of JPL. Funding was provided by NASA.

This is the same team that reported on accelerated glacial melt in West Antarctica, as discussed in an earlier Ice Blog post. Together, the papers “suggest that the globe’s ice sheets will contribute far more to sea level rise than current projections show,” Rignot said.

Indeed. These scientists are telling us the IPCC forecasts were way too low. This could have huge consequences for coastal communities all around the globe.

Unfortunately, a lot of people (even those you would expect to know better) tend to mix up “Arctic” and “Antarctic”. It all goes into the category of “melting ice”, and they think they have heard it all before. What they still don’t realize is that this is something that concerns us all, and that these two polar areas are of huge significance to the world climate as a whole and global sea level. When those two Antarctic studies were released, there was a flurry of news coverage. The challenge for us journalists is how to follow this up and stop the attention curve from dropping.

The other interesting piece of recent Greenland research was conducted by the Dartmouth College Thayer School of Engineering and the Desert Research Institute and reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences. It concludes that ash from Northern hemisphere forest fires combined with rising temperatures to cause large-scale surface melting of the Greenland ice sheet in 1889 and 2012.

The researchers say their findings contradict conventional thinking that the melting was driven by warming alone.

The findings suggest that continued climate change will result in nearly annual widespread melting of the ice sheet’s surface by the year 2100.

Melting in the dry snow region does not contribute to sea level rise, but when the meltwater percolates into the snowpack and refreezes, the surface is less reflective. This reduces the albedo.

Let me give the (almost) last word to the study’s lead author Kaitlin Keegan.

“With both the frequency of forest fires and warmer temperatures predicted to increase with climate change, widespread melt events are likely to happen much more frequently in the future”.

It figures.

Feedback