Search Results for Tag: ocean acidification

Ice and mud, glorious mud

Most of the time our ship is out of range of internet connectivity, so this post will be delivered to you from the research base Ny Alesund. My hosts and the station staff were kind enough to arrange a special little boat and a survival suit for a trip through the dark but fascinating polar night. This is only possible because tonight we are still relatively close, with the ship collecting samples in Kongsfjorden, on the north-west side of Spitsbergen. This is an open fjord with a relatively free connection to adjacent shelf. It’s 20 km long, between 4 and 10 metres wide and a maximum depth of 400 metres. This means it is largely influenced by both Atlantic water and Arctic water. It also gets a discharge of fresh water and sediments from adjacent glaciers, which we will be looking at more closely in the next few days. It has been an action-packed day today, watching polar marine night researchers in action. Night research during the day sounds odd, but I can assure you it is certainly dark enough –at any time of day.

Muddy secrets Sergei Korsun from St. Petersburg university and PhD student Olga Knyazeva were out on deck preparing a box corer, a big box-shaped instrument to go down to the seabed and bring up samples of sediment. The teamwork between scientists and crew seems to work brilliantly. The crew operate the lifting and lowering equipment and all sorts of other gear. The scientists collect their samples from it and take them in to the ship’s lab.

“Just a load of mud”, quips Sergei, and there is certainly plenty of it sploshing about in the course of the operation. No wonder there are no outdoor shoes allowed inside.

Olga drains off the water so that only the sediment is left. These two are interested in foraminifera or forams, one-celled organisms. Ice Blog readers may remember I discussed them here some time ago, in connection with research on ocean acidification. German scientists actually wrote a children’s story with Tessi and Tipo, two of these tiny ocean creatures, as the main characters. The focus there was on how increasingly acid seas are dissolving the protective shells of many organisms, especially in cold, Arctic water, where the process is faster. Every creature counts! So why should we be interested in these forams in particular? No question about it, says Olga. There are so many of them, they account for a huge proportion of biomass and we know far too little about what they are up to in the winter. Given their important role in the ecosystem, what they do in winter is something we really ought to know. The season of winter is just too long to be ignored any longer, says Olga. And ultimately, even the tiniest creatures play a role in the global foodweb. Sergei mentions another reason why climatologists and those interested in the history of the planet are so interested in these tiny creatures. They fossilize, so that scientists can use samples from the seafloor to get a record of earth’s history that goes back a very long way.

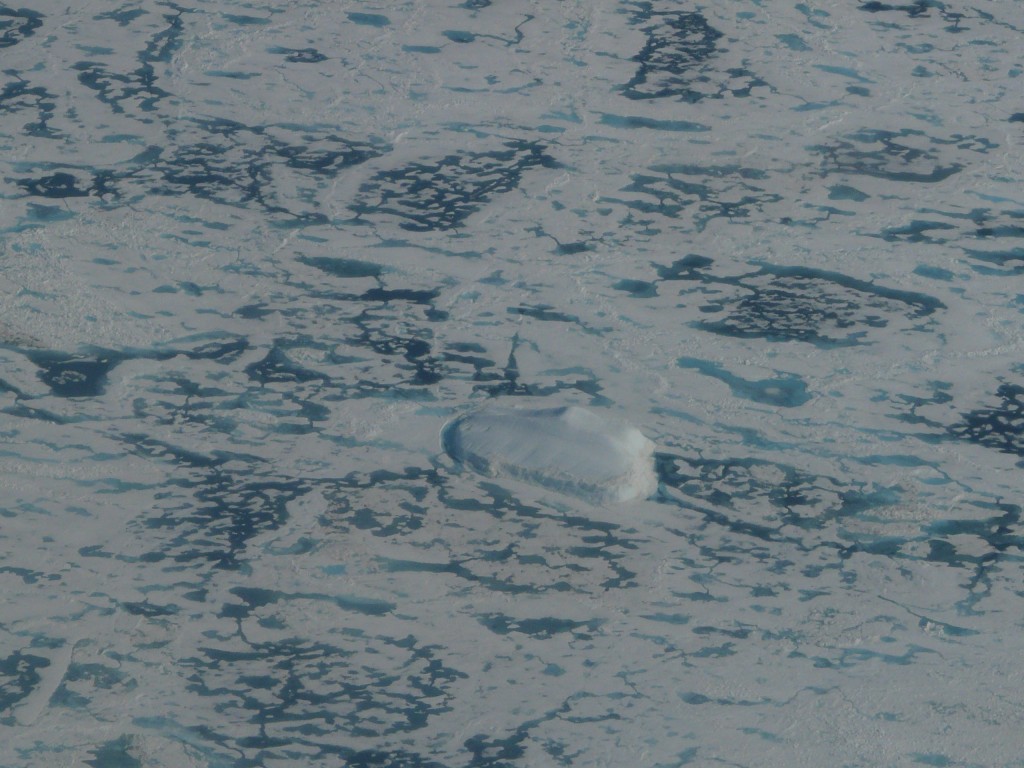

Inner clocks without daylight? Shortly afterwards, I joined Sören and Lukas from Germany’s Alfred-Wegener Institute for one of their four-hourly net-dropping exercises. For this, a big hatch is opened on the laboratory deck. This brought added excitement as there were a lot of beautifully shaped chunks of ice just floating past. Iceblogger’s delight!

We could also see the hills in silhouette in the background. Clearly there are indeed many shades of “dark”. Seagulls are following us constantly. No doubt they know fish and shrimps are being caught and are always on the lookout for an easy, tasty morsel. In this climate, I don’t blame them. And it is kind of reassuring to have their company, bright in the ship’s lights against the dark sky and sea. The wind felt icy, but the experts up here tell us it is actually relatively mild. Anyway, our two scientists dropped a longish thin net attached to a sort of circular hoop out the hatch, sampling the water.

When it came in, they take samples of small jellyfish, copepods and krill, for a fascinating project to find out about the “biological clock gene”. How can some marine organisms migrate vertically in a 24-25 hour cycle, without light to trigger this? More about that when I’ve interviewed the experts over the next couple of days.

The advantages of winter If you have been waiting for the answer to the question about reproduction in the last blog, I won’t keep you in suspense any longer. Given that the reason is unlikely to be an ideal food supply for the “babies”, some of the scientists on board think the reason could be that there fewer predators about to eat the young, if they arrive in winter. Does that seem plausible? The next post may be a day or two in arriving, as the ship will be out of range from tomorrow onwards. But I promise plenty more to come as soon as we are back in internet range. (How on earth did we live without it?!)

Acid Arctic Ocean and Russell Brand?

Is ocean acidification a term you are familiar with? If you are a regular Ice Blog reader, I would like to think you will be. But I am prompted to ask this question because the term came up during a discussion at a weekly evening class I attend, and I was flabbergasted that none of the people there had a clue what it meant. These were all university-educated professionals. That means we in the media have our work cut out for us explaining how climate change is making the seas more acidic, and why this is something we should be worried about.

This incident has reminded me that we journalists have to avoid assuming that everyone is familiar with the terms we use in our coverage on a regular basis. Climate change is the kind of topic where you want to reach a specialist audience, but also the vast majority of the population. We all have to change our habits to reduce CO2 emissions, and we all have to vote for the politicians who have the responsibility for energy and environment policy. That means we need to talk about the problems in a way everybody understands.

I am encouraged to see the BBC website had a longer article on the threat of ocean acidification a few days ago. I don’t think it has made its way into the tabloids though, correct me if I am wrong.

I was made very aware of the issue during a trip to Arctic Spitzbergen in 2010 with a team of scientists monitoring just what happens to the life forms in the sea when it becomes more acidic because it is absorbing so much of the CO2 we emit. The polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

Greenpeace provided scientists with logistic support for the ocean acidification experiments off the coast at Ny Alesund, Spitzbergen. (Pic: Irene Quaile)

Towards the end of last year, I interviewed Professor Alex Rogers from the University of Oxford, who is also the scientific director of the International Programme on the State of the Oceans, which had just published a major study on acidification.

Listen to the interview:

He told me: “The oceans are taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we’re producing at the moment. While this is slowing the rate of earth temperature rise, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in a very profound way.”

Carbon dioxide reacts with sea water to form carbonic acid. Gradually, this makes oceans more acidic.

Threat to marine life

Sea water is already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. According to the IPSO report, it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100.

Over the last 20 years, scientists around the world have been conducting laboratory experiments to find out what that would mean for the flora and fauna of the oceans. Ulf Riebesell of the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, a lead author of the report, conducted the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of the Arctic island of Svalbard in 2010. This was the project I visited.

Giant test-tubes were lowered into the ocean to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades. The experiments showed that increasing acidification decreases the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Scientists say some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Hard times for coastal residents

All this will have severe economic and social consequences. Ultimately, acidification will affect the food chain. Tropical and sub-tropical areas with warm-water corals are going to suffer. Coral reefs are home to numerous species, serve as nurseries for fish and are a valuable tourist attraction. They also protect coastlines against waves and storms.

At the same time, the polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Riebesell told me the experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.” What a horrific prospect.

The Antarctic is already affected. IPSO’s Alex Rogers told me: “We’re seeing instances where we’re finding tiny shelled molluscs, tiny snails that swim in the surface of the oceans, with corroded shells.”

These creatures play a key role in the marine food chain, supporting everything from tiny fish to whales. “One of our primary sources of marine-derived protein is in rapid decline,” says Monty Halls, manager of the UK-based Shark and Coral Conservation Trust. He describes ocean acidification as the “most serious threat to our children’s welfare.” Monty is working to produce video and cartoon material to interest the younger generation in the need to change our behavior to protect marine life.

Two German scientists Antje Funcke and Konstantin Mewes have written and illustrated a children’s story called Tipo and Tessi to make kids aware of the need to protect the ocean. So far, it has only been published in German. The English translation is available, but so far there is a lack of funding for publication.

Vicious circle of climate change

Scientists are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate. That means the more acidic the ocean becomes, the less capacity is has to act as a buffer.

Alex Rogers sees a further problem: “Carbonate structures actually weigh down particular organic carbon. In other words, they help carbon to sink out of the surface layers of the ocean into the deep sea. Anything that interferes in that process can potentially accelerate the rate of CO2 increase in the atmosphere.”

And that would be very dangerous. “The rates of CO2 increase we are seeing at the moment are probably as high as they’ve been for the last 300 million years,” says Rogers.

The IPSO scientists draw an unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions. They say a lot of these major extinction events occurred in connection with high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today.

The BBC article I mentioned earlier also mentions new research by scientists at Exeter University, indicating that increasing acidity creates conditions for animals to take up more coastal pollution, like copper. That would mean not only creatures with calcium-based shells would be endangered.

Find a celebrity champion?

The experts stress that it is not too late to halt the acidification process, although the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. This brings me back to the topics of recent Ice Blog posts: the UN climate negotiations and the need for urgent action. And of course, to the mention in the title above of the British comedian Russell Brand. This relates to another issue I have been writing about recently: the question of celebrity involvement and whether that can help inform people about and interest them in topics like climate change and the acidification of our oceans. My commentary on this, with regard to Leonardo di Caprio at Ban Ki-moon’s September summit in New York, sparked some interesting discussions.

Just this morning I was reading about Russell Brand and how his new book calling for a revolution on all kinds of issues is attracting huge interest. I have noticed that people otherwise completely uninterested in politics and social issues are at least paying some attention because their favourite comedian is talking about them. Maybe we have to get Russell Brand on board. I’m not sure what kind of action he would advocate, but there would certainly be a lot fewer people who could say they’d never heard of ocean acidification.

Polar regions hit by ocean acidification

In 2010 I watched the start of the first in situ ocean acidification experiments off the coast at Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen, as part of the EU’s EPOCA project. Mesocosms, or giant test-tubes, were being taken out to sea by the Greenpeace ship the Esperanza. (Pic: Irene Quaile)

Did you notice much about the problem of CO2 in the oceans in the (already minimal in most places) coverage of the Warsaw climate conference? A summary of the report published recently by the International Programme on the State of the Oceans (IPSO) was presented at the meeting to draw attention to the dangers posed by acidification for ecosystems, humankind and, in form of a feedback effect, for the climate warming which is causing it in the first place. If that sounds complicated, but intriguing enough to warrant further interest, you might want to listen to an interview I recorded this week with Alex Rogers. He is a Professor of Conservation Biology at the Dept. of Zoology and a Fellow of Somerville College, University of Oxford. Amongst his many other titles, he’s the Scientific Director of IPSO. He told me it was a “fascinating coincidence” that the report was published just after the latest IPCC report, which noted, amongst other things, that atmospheric temperatures hadn’t risen as much over the last ten years or so as had been expected. One main reason suggested is that the excess heat is being taken up by the ocean, especially the deep ocean. And that fits perfectly with the findings of the big ocean survey and collation of data, says Prof. Rogers.

I also talked to Ulf Riebesell from the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, Germany, a lead author of the report and the scientist who has been in charge of the in situ acidification experiments in the Arctic .You might also enjoy in my report from that venture.

That interview is in German, so I’m not putting it up here, but the content will be flowing into an article for the DW website very soon. Meanwhile, here’s Professor Rogers:

Atlantic cod pushing out Arctic relatives?

When I visited the AWI Biological Institute on the German North Sea island of Helgoland last year for a story on how climate change is affecting marine life, the Institute’s Director Karen Wiltshire mentioned to me that cod was disappearing from the waters around the island. The Atlantic cod, it seems, are moving north, a trend confirmed by a recent research cruise by scientists from the Alfred-Wegener-Institute (AWI).

![]() read more

read more

Arctic Ocean acidification – kids’ stuff?

June 8th is World Oceans Day, so I am taking the opportunity to draw attention to the increasing acidification of the Arctic Ocean. CO2 makes the seas more acidic when it is absorbed from the air. This process is faster in cold water, making the Arctic particularly susceptible to this climate change impact. A study published earlier this year by scientists from the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), based on monitoring over the last three years shows that the Arctic Ocean is rapidly accumulating carbon dioxide, leading to increased ocean acidification. This is having an impact on the marine ecosystem. The probem is exacerbated by increasing flows of fresh water from rivers and melting land ice. Creatures like pteropods, or sea butterflies, are likely to be harmed. Any marine life that needs calcium to form its skeleton or shell will be at risk, followed by the predators dependent on them.

My attention was drawn recently to a video cartoon produced back in 2009 aimed at teaching young people about ocean acidification, a concept which is not easy to grasp. I think it is great! Well done kids!

The animation was produced by pupils from Ridgeway School (Plymouth, UK) and Plymouth Marine Laboratory with funding from EPOCA the European Project on Ocean Acidification (www.epoca-project.eu). I recommend a look. Adults can learn something from it as well as kids! It is a great way to explain the concept, an entertaining video, and the idea of teaching young people about the problems our lifestyles are causing is a key element in securing a sustainable future. I recently acquired a copy of a book in German with a similar aim: Tessi & Tipo. Die Entdeckung der Ozeanversauerung. (ISBN 978-3-86918-204-9)It was written by Antje Funcke and Konstantin Mewes, young scientists at AWI, the Alfred—Wegener-Institut, Germany’s polar science body. Nice work!

The Oslo-based “Center for International Climate and Environmental Research” has a good summary of the AMAP report on its website. I reported on an EPOCA experiment to measure ocean acidification in the Arctic off Spitzbergen in 2010. Greenpeace had helped the scientists by offering the Esperanza to transport the “mesocosms” for the experiments up north. The story is online here: Scientists enter unusual alliance to study Arctic Ocean.

Feedback