Search Results for Tag: research

Cryosphere in Crisis?

You can’t say the latest research results on the thinning of the West Antarctic ice sheet didn’t make the media. From the news agencies through the quality media and even publications not known for their detailed science or environment coverage – nearly all reported that two separate studies each independently come to the conclusion that parts of the West Antarctic ice sheet are already “collapsing”. They say this could result in a considerable sea level rise within the next century or two. This would have devastating consequences for low-lying coastal areas around the globe.

No-one can really say they didn’t know about this. For once, the Antarctic ice has made into the headlines of the mainstream media. This is the region people tend to think of as having “eternal ice”, where global warming will “not make much difference”. There are those who criticize the media for sensationalism or exaggeration by taking over the term “collapse” for a process which will still take hundreds to thousands of years. See for example Andrew Revkin’s post on Dot Earth (New York Times), (and an excellent response by Tom Yulsman in ImaGeo: (Discover Magazine). But, semantic discussions apart – as Yulsman puts it:

“On a human timescale, 200 years or more for the start of rapid disintegration is a very long time indeed. But on a geologic timescale, it is the blink of an eye. And that’s important to keep in mind too — that in a blazing flash, geologically speaking, we humans are managing to remake the life support systems of our entire planet. This is why I think today’s news may eventually be seen as having historic significance”. At any rate, he concludes “it is yet another clear sign that human-caused changes to the planet once regarded as theoretical are now very real”.

Indeed Tom. The question is: what are we going to do about it? Has it set the alarm bells ringing? Did anybody see a rash of reactions promising quick action on reducing emissions to mitigate climate change? If so, please point me in the right direction. So far, I haven’t seen any indication of anything other than business as usual.

The West Antarctic ice sheet contains so much ice that it would raise global sea level by three to four meters if it melted completely. As it sits on bedrock that is below sea level, it is considered particularly vulnerable to warming sea water. Until now, scientists assumed it would take thousands of years for the ice sheet to collapse completely. The two new studies indicate that could happen much faster – as early as 200 years from now or, at the most, 900. Both research teams, using different methods and looking at different parts of the ice sheet, conclude that the trend is probably unstoppable.

The NASA study published in “Geophysical Research Letters” uses data from satellites, planes, ships and measurements from the shelf ice to examine six large glaciers in the Amundsen Sea over the last 20 years. The second report, from the University of Washington published in the journal “Science,” uses computer models to study the Thwaites glacier. It is considered of particular importance because it acts as a type of “lynch pin”, holding back the rest of the ice sheet.

According to NASA researcher Eric Rignot, the glaciers in the Amundsen Sea sector of West Antarctica have “passed the point of no return.” He told journalists this would mean a sea level rise of at least 1.2 meters (3.93 feet) within the next 200 years.The University of Washington scientists worked out, using topographical maps, computer simulations and airborne radar, that the Thwaites glacier is also in an early stage of collapse. They expect it to disappear within several hundred years. That would raise sea levels by around 60 centimeters (23.62 inches). The NASA study showed that sea level rises of 1.2 meters are possible

The good news, according to author Ian Joughlin, is that while the word “collapse” implies a sudden change, the fastest scenario is 200 years, and the longest more than 1,000 years. The bad news, he adds, is that such a collapse may be inevitable: “Previously, when we saw thinning we didn’t necessarily know whether the glacier could slow down later, spontaneously or through some feedback,” Joughlin says. “In our model simulations it looks like all the feedbacks tend to point toward it actually accelerating over time. There’s no real stabilizing mechanism we can see.”

The latest IPCC report does not adequately factor ice loss from the West Antarctic ice sheet into its projections for global sea level rise, on account of a lack of data. These “will almost certainly be revised upwards,” according to Sridar Anandakrishnan from Pennsylvania State University at the presentation of the University of Washington study. The scientist was not involved in the research.

NASA glaciologist Rignot said he was taken aback by the speed of the changes. “We feel this is at the point where … the system is in a sort of chain reaction that is unstoppable,” he said.

Rignot also makes the key point that this development tells us not only about the area down at the South Pole, but about the whole climate system: “This system, whether Greenland or Antarctica, is changing on a faster time scale than we anticipated. We are discovering that every day.”

My last two blog posts have been about melting of the Greenland ice sheet and melting even in the East Antarctic, which is usually cited as the last bastion against ice-destroying climate change. We are subjecting our cryosphere to huge pressures and have set a “snowball” rolling, which is picking up momentum and will ultimately carry masses of ice into a rising ocean.

Rignot says even drastic measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions could not prevent the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet. That is a terribly depressing thought. I would like to think this will prove wrong. But if there is any chance to avert that disaster and preserve our polar ice for thousands of years rather than just a few hundred, surely the time for action is now?

Will Antarctic share Arctic’s fate?

While the Arctic is melting twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and protests continue against the race for oil at huge risk to the sensitive environment, the icy regions around the south pole were long considered immune to climate change. But melting glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula in recent years sparked doubts in the scientific community about just how stable the western region of Antarctica really is. Earlier this year, I wrote an article on the irreversible melt of the Pine Island glacier on western Antarctica. The huge iceberg that broke off last November has been in the news again, heading for the open sea.

Only the huge icy vastness of Eastern Antarctica still appeared to be safe from the perils of a warming climate. Now experts from Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) have published findings indicating that this too might no longer be the case. In a study published in “Nature Climate Change“, they write that the melting of just a small volume of ice on the East Antarctic coast could ultimately trigger a discharge of ice into the ocean which would result in unstoppable sea-level rise. They are talking about tomorrow or the next decade. Still, the prospect of more irreversible thawing in the Antarctic is a very worrying one.

“Previously, only the West Antarctic was thought to be unstable. Now we know that the eastern region, which is ten times bigger, could also be at risk”, says Anders Levermann, co-author of the study. The findings are based on computer simulations which make use of new, improved data from the ground beneath the ice sheet.PIK scientist Levermann was one of the lead authors of the sea-level section in the latest IPCC report.

“The Wilkes Basin in East Antarctic is like a bottle that is tilted”, says Matthias Mengel, lead author of the new study.”If you take out the cork, the contents will spill out”. At the moment, the “cork” is formed by a rim of ice at the coast. If that were to melt, the huge quantities of ice it holds back could shift and flow into the ocean, raising sea levels by three to four meters. Although air temperatures over Antarctica are still very low, warmer ocean currents could cause the ice along the coast to melt.

So far, there are no signs of warmer water of this sort heading for the Wilkes Basin. Some simulations suggest though that the conditions necessary for the “cork” to melt could arise within the next 200 years. Even then, the scientists say it would take around 2000 years for sea level to rise by one meter.

According to the simulations, it would take 5,000 to 10,000 years for all the ice in the affected region to melt completely. “But once this has started, the discharge will continue non-stop until the whole basin is empty”, says Mengel. “This is the basic problem here. By continuing to emit more and more greenhouse gases, we could well be triggering reactions today that we will not be able to stop in the future. ” Indeed.

The IPCC report predicts a global sea-level rise of up to 16 centimeters this century. As this could already have devastating impacts on many coastal areas around the globe, any additional factor is of key importance to the calculations. “We have presumably overestimated the stability of East Antarctica”, says Levermann. Even the slightest further increase in sea level could aggravate flooding risks for coastal cities like New York, Tokyo or Mumbai.

At the moment, the largest contribution to Antarctic ice loss and rising sea levels comes from the Pine-Island glacier in West Antarctica. As I mentioned at the start, a huge iceberg, which broke off from the glacier last year, is currently floating into the open waters of the Southern Ocean. French glaciologist Gael Durand from Grenoble University told me in an interview the huge glacier had already reached a point where its continued melting is irreversible, regardless of air temperature or ocean conditions.

Why high suicide rates in Arctic Russia?

Back at DW headquarters in Bonn after returning from Arctic Frontiers in Tromso at the weekend, I am sorting out notes and interviews with a wide range of experts on Arctic issues from all over the world.

One interview I would like to share with you here on the Ice Blog is a talk I had with Dr Yuri Sumarokov from the Northern State Medical University in Archangelsk in north-west Russia. It is the northernmost medical school in Russia and has a special focus on research into Arctic medicine and issues affecting the health of people in the Arctic.

People in the Arctic regions of Russia have a much higher suicide rate than in other parts of the country. The rate is higher again amongst indigenous people. Sumarakov, himself a medical doctor, shared some insights into the ongoing research with me. The topic is not new and certainly not limited to Russia. It seems though to be a topic that is not talked about enough, especially amongst politicians – and in the media. So let’s make a start. Please have a listen. There is plenty of food for thought and I for one feel motivated to find out a little more:

Yuri Sumarokov, MD, is Head of the Dept. of International Cooperation at Northern State Medical University (NSMU), Russia.

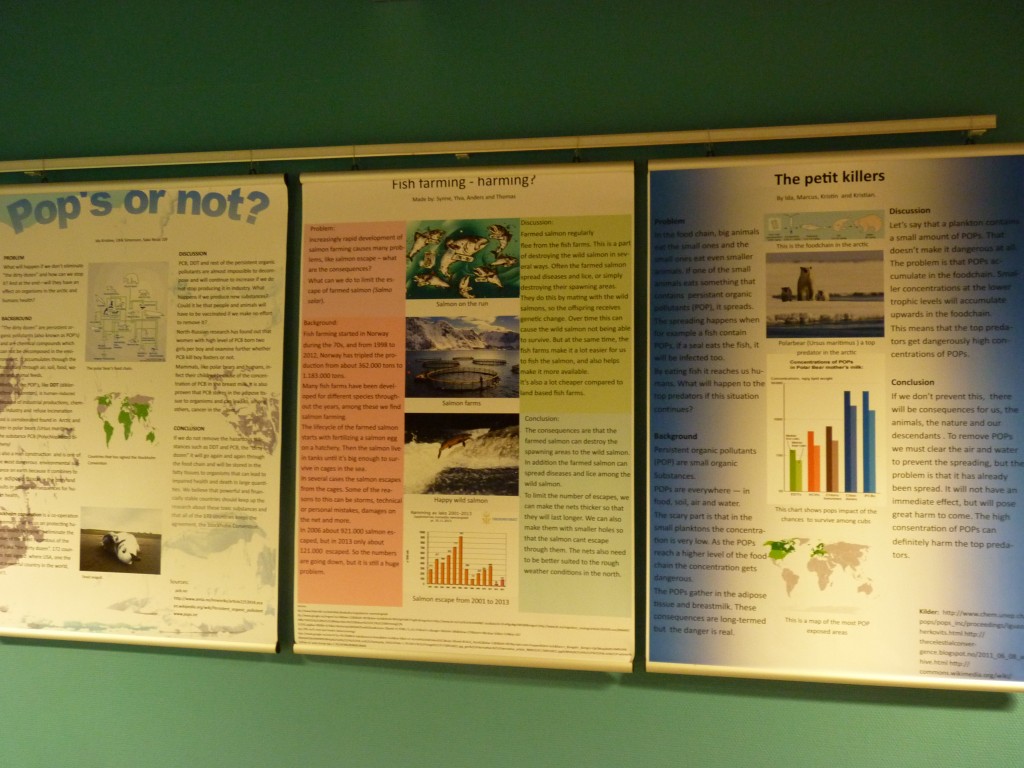

Kids, POPS and Arctic Science

Norway, believe it or not, is having problems recruiting scientists and qualified personnel for the Arctic. The generous education system attracts plenty of foreign students, it seems. But there is a lack of Norwegian PhD students. Not that the country doesn’t welcome foreign students, but understandably they would like to have people who stay on in the Norwegian Arctic as well as those who take their qualifications back home to wherever. For that reason, the Arctic Frontiers conference and APECS, the Association of Polar Early Career Scientists decided to “start them young” and invited pupils from two local schools to an Arctic science workshop in the planetarium of the Tromso Science Centre, the country’s northernmost. As I arrived, I found myself overtaken by youngsters rushing down to have a look at the gadgetry and a hands-on shot at scientific experiments. This is the kind of place that interests young people in the workings of nature and technology.

Kirsten and Ida talked to me (in English, great language skills) about their project. They had made a poster of the type displayed at scientific conferences. Their subject: Persistant Organic Pollutants, POPs. They told me the increasing concentration of these up here in the remote Arctic environment is something that worries them.

The posters are entered in a competion, with awards and attendance at next year’s big Arctic conference event awaiting the winners. The girls were reserving judgement about whether Arctic science would be their future careers. But they were willing to give it due consideration and looking forward to the “science show” at the planetarium. Let’s see which pupils turn up here again next year!

Centre Director Tove Marienborg demonstrates the energy involved in using the “Spark” or kick-sled.

Rovaniemi: Finland and the Arctic

Rovaniemi is where I would like to have spent the last few days. From Dec. 2nd to 4th, the first of a series of Arctic conferences was held there, organized by the city of Rovaniemi and the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland.

Rovaniemi, a Finnish town right on the edge of the Arctic circle, is known to “Arctic buffs” because of the “Rovaniemi Process”, a Finnish initiative for Arctic environmental co-operation, which ultimately led to the adoption of the “Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy”, signed in Rovaniemi in 1991. This in turn played an important role in the establishment of the Arctic Council

In the spirit of that “Rovaniemi Process”, the city and the University’s Arctic Centre decided to organize a series of conferences, this being the first one. Finland, like all the northern states, is trying to assert its position in the region against the background of climate change and growing international interest.

Earlier this year, I received a copy of a very useful booklet produced by the Arctic Centre of the University of Lapland. It’s entitled “The Arctic Calls. Finland, the European Union and the Arctic Region“. The authors are Markku Heikkilä and Marjo Laukkanen, both based at the Arctic Centre. Its aim is to “put a human face on the Arctic Region”, and it does that very well, looking across the whole region. President Sauli Niinistö wrote the foreword to the publication. He mentions Finland’s initiative to establish an EU Arctic Information Centre in Rovaniemi, which I am following with interest.

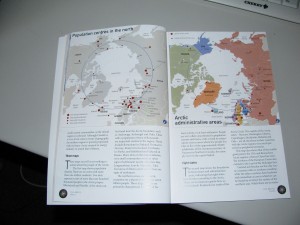

Useful maps and info on the Arctic and its peoples

The European Union Arctic Information Centre (EUAIC) initiative is an international network of 19 leading Arctic research and outreach institutions from the various European Union Members States, and the EEA countries. It was started in 2009 as a professional network of European institutions aiming to provide information, outreach and insight into Arctic issues. The network’s objective is to provide the European Union, its citizens, institutions, companies and member states with a reliable source of information on what is happening in and concerning the Arctic. The EUAIC initiative network aims to “facilitate two-way communication between experts, decision makers, stakeholders and the public”, according to its website.

The initiative is organized as a network, making use of existing expertise and the infrastructures of its members. Its headquarters are located at the Arctic Centre in Rovaniemi. Currently there are nineteen partners. The European Commission selected the consortium to carry out a key one million euro project to produce a “Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment of development of the Arctic”. The project should be completed in 2014 and should make for interesting reading.

Bearing all this in mind, it’s worth keeping an eye on what comes out of the Rovaniemi conference. And I’d recommend the publication, “The Arctic Calls”, ISBN 978-952-281-065-6. It has interesting interview, maps, photos and insight. You can also get it from the Arctic Centre or download an online version.

Let me just finish by quoting from the final pages:

“The images of icebergs drifting out to sea have turned from symbols of freshness to symbols of disappearance. They have become images of a unique world that is undergoing drastic change and is about to lose many of its characteristics.” How right you are.

Feedback