Search Results for Tag: sea ice

Earth Day, Climate pact signing – and the Arctic?

How are you feeling this Earth Day? In some ways it could mark a turning point for the planet, with some 165 countries signing the Paris climate treaty at UN headquarters in New York. But, as, always, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. And so far, I’m not sure it is quite tasty enough.

The trouble is, signing agreements alone is not enough. They have to be turned into action. The world is heating up way too fast, and the transition to an emissions-free world is far too slow. Yes, we can do it, I am convinced. But as well as the political will to sign an agreement, we need the political will to implement measures which will be unpopular with businesses and consumers because they mean major changes to how we work, trade and live.

In the meantime, the Arctic is facing a decline in sea ice that could equal or even beat the negative record of 2012.

Sea ice physicists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), have evaluated current satellite data on the thickness of the ice cover. The data show that the Arctic sea ice was already extraordinarily thin in the summer of 2015 and comparably little new ice formed during the past winter. Speaking at the annual General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna, AWI sea ice physicist Marcel Nicolaus said data collected by the CryoSat-2 satellite revealed large amounts of thin ice that are unlikely to survive the summer.

Hard to forecast

Predicting the summer extent of the Arctic sea ice several months in advance still poses a major challenge to scientists and meteorologists. Between now and the end of the melting season, the fate of the ice will ultimately be determined by the wind conditions and air and water temperatures during the summer months. However, conditions during the preceding winter lay the foundations.The AWI scientists say this spring, conditions are as “disheartening as they were in 2012”, when the sea ice surface of the Arctic went on to reach a record low of 3.4 million square kilometres.

At the end of March, the Arctic sea ice was at a record low winter maximum extent for the second straight year, according to scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and NASA. Air temperatures over the Arctic Ocean for the months of December, January and February were 2 to 6 degrees Celsius (4 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit) above average in nearly every region.

This year’s maximum winter extent was 1.12 million square kilometers (431,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average of 15.64 million square kilometers (6.04 million square miles) and 13,000 square kilometers (5,000 square miles) below the previous lowest maximum that occurred last year.

The September Arctic minimum began drawing attention in 2005 when it first shrank to a record low extent over the period of satellite observations. It broke the record again in 2007, and then again in 2012. The March Arctic maximum tended to attract less attention until last year, when it was the lowest ever recorded by satellite.

Ice conditions “catastrophic”

Recently, here on the Ice Blog, I published an account by Larissa Beumer, one of a team of Arctic experts on board the Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise, which has been checking the ice conditions the Arctic archipelago of Spitsbergen. From the ship, she told me the ice conditions were “catastrophic and way outside of normal variations”. She reported transport problems, with many of the usual routes inaccessible by dog sled or snow mobile. She talked of a lack of ice in places where navigation is usually impossibly up to June or July.

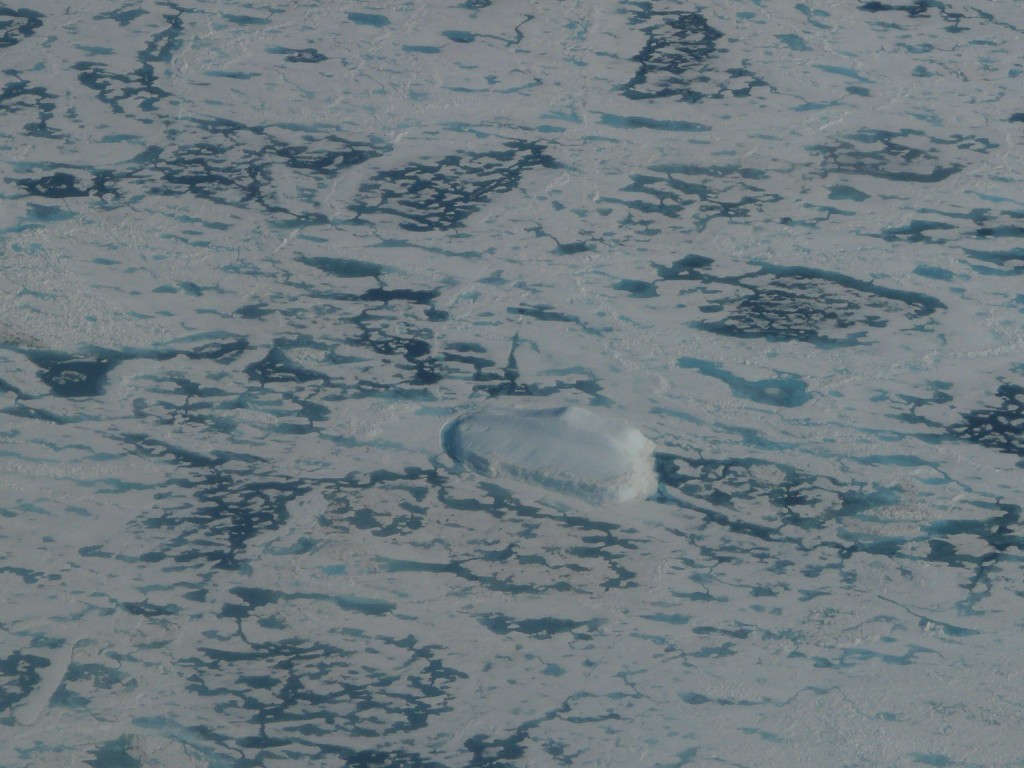

Ice and open water, photographed by Nick Cobbing for Greenpeace, from the Arctic Sunrise, off Spitsbergen.

On thin ice

AWI scientist Marcel Nicolaus says new ice only formed very slowly in many regions of the Arctic, on account of the particularly warm winter.

“If we compare the ice thickness map of the previous winter with that of 2012, we can see that the current ice conditions are similar to those of the spring of 2012 – in some places, the ice is even thinner,” he told journalists at the Vienna Geosciences meeting.

Nicolaus and his colleague Stefan Hendricks evaluated the sea ice thickness measurements taken over the past five winters by the CryoSat-2 satellite for their sea ice projection. They also used data from seven autonomous snow buoys, which they placed on ice floes last autumn. These measure the thickness of the snow cover on top of the sea ice, the air temperature and air pressure. A comparison of their temperature data with AWI long-term measurements taken on Spitsbergen has shown that the temperature in the central Arctic in February 2016 exceeded average temperatures by up to 8 °Celsius.

Breaking ice record

In previously ice-rich areas like the Beaufort Gyre off the Alaskan coast or the region south of Spitsbergen, the sea ice is considerably thinner now than it normally is during the spring. “While the landfast ice north of Alaska usually has a thickness of 1.5 metres, our US colleagues are currently reporting measurements of less than one metre. Such thin ice will not survive the summer sun for long,” Stefan Hendricks said.

The scientists say all the available evidence suggests that the overall volume of the Arctic sea ice will be decreasing considerably over the course of the coming summer. They suspect the extent of the ice loss could be great enough to undo all growth recorded over the relatively cold winters of 2013 and 2014. “If the weather conditions turn out to be unfavourable, we might even be facing a new record low,” Stefan Hendricks said.

So the AWI researchers fear we are going to see a continuation of the dramatic decline of the Arctic sea ice throughout 2016. From that point of view, the signing of Paris climate pact comes way too late. UN Secretary-General Ban ki-Moon is stressing that this can only be the beginning, and that the mammoth task of decarbonising the economy still lies ahead. Here’s hoping the Paris Agreement will not just be a piece of paper which governments use to salve their consciences. Here in Germany, people are concerned that the government will not reach its ambitious climate targets at the present pace. Given that this country has already made remarkable progress in the transition to renewable energy for its electricity production, that is a worrying trend. And other major emitters still have even more to do if that two degree, let alone the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit to global warming is to be more than a very hot piece of pie in the steadily warming sky.

A letter from Svalbard’s dwindling sea ice

Greenpeace’s Larissa Beumer on board the Arctic Sunrise in the Spitsbergen archipelago. (Pic: Nick Cobbing, courtesy of Greenpeace).

The Arctic sea ice has reached its maximum winter extent for this season, and it was a record low, as reported here on the Iceblog.

The Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise is currently sailing in the Hinlopen Strait in the Arctic archipelago of Spitsbergen, checking out the ice conditions. Larissa Beumer is on board. I wanted to know what the ice situation was like, and she sent me this report. Photographer Nick Cobbing is also on board, so that means we can have a couple of his wonderful pics on the Iceblog. Thanks Nick and Greenpeace.

LARISSA BEUMER: “The ice conditions up here vary considerably from year to year. But this year is really extreme. On the west coast, almost none of the fjords are frozen up. The only exceptions are Dicksonfjord and Van Mijenfjord (and that one isn’t frozen up as far as it “normally” is).

On the east coast, there is no solid, stable ice, frozen through like it normally is. The ice there is moving a lot, it has often broken apart and been blown together again by the wind, so it’s not reliable. (And in general there is less ice there as well).

That means tourists and locals are very severely restricted in their activities. Dog sled and snowmobile tours normally mainly use the frozen-over fjords on the west coast. But this year, a lot of the usual main routes are not usable. That means some of the main destinations like Pyramiden (and Isfjord radio) can only be reached by taking major detours over the glacier systems. The east coast is another of the main destinations for snowmobile excursions. You can still get there quite well, but driving over the ice is more risky than usual. (One tourist group went through the ice this season, but nobody was hurt).

We sailed north along the west coast, then east along the north coast to the Hinlopen strait. We didn’t encounter any large stretches of ice masses anywhere on route. Normally, there is so much ice up there in winter that the route is only navigable from June or July.

Actually, in “normal” years, the pack ice extends down from the north to the northern coast of Spitsbergen right into summer. Now it’s just the bginning of April and the pack ice only starts much further north. Sailing to Nordaustlandet is normally still challenging in August, because of the ice conditions. This year, it’s more or less navigable already. It used to be that expedition cruises billed as “Circumnavigation Cruises” had to change their route because the ice in the north was still so thick they couldn’t get through. I think at the moment you could already do a circumnavigation without any problems.

The ice we can see is mainly fresh ice, one-year ice, with open water here and there and a lot of breaks in it. As I said before, it’s moving about, breaks and is pushed together again. As far as we can see, the thickness is relatively varied, but there is a lot of thin ice amongst it.

The current ice chart from the Norwegian Meteorological Institute shows that a lot of ice from the south has been pushed into the Hinlopen Strait by the wind over the last two days. All this ice just wasn’t there a few days ago. It comes from the pack ice in the north-east, towards Franz-Josef-Land. So it’s not ice that formed here.

So, all in all, it seems fair to say that this year the ice conditions up here around Svalbard are catastrophic and way outside of normal variation. Oscar, our polar-bear guide, says he has never experienced anything as bad as this in the 13 years he has being living here.”

Larissa Beumer, on board the Arctic Sunrise, Spitsbergen.

Time to cruise the Northwest Passage?

When I came across a story about a sold-out cruise through the North-West Passage planned for this summer on a giant liner carrying around a thousand passengers, I couldn’t help remembering a workshop I attended in Tromsö in 2014, organized by the Washington-based Arctic Institute, Center for Circumpolar Security Studies, within the framework of Arctic Frontiers. I wrote a story afterwards entitled “Are we prepared for a catastrophe in the Arctic?”. The answer I got from the experts was definitely a “no”.

One scenario the experts had worked through made a particularly strong impression on me. It envisaged a cruise ship hitting an iceberg off the coast of Greenland. It was not a happy picture. More people on the ship than in the communities on land, not enough helicopters, not enough accommodation, too little medical capacity, in short a lack of infrastructure to cope, all round.

“A whole new dimension”

With the “Crystal Serenity” set to head through the Northwest Passage this August, I decided it was time to call up Malte Humpert, Director of the Arctic Institute, to get his view on the safety aspects of this – and the current state of shipping activities in the Arctic. He said this was a whole new dimension, with almost 2000 people, including passengers and around 600 crew:

“There’s varying challenges, ranging from ice flows to uncharted depths to unpredictable waters, and so the range of risk is pretty high. Of course one can take precautions like ice pilots, having rescue equipment, icebreakers on standby, but you’re still in a very remote area with very small populations, very limited capacity. So the larger these vessels get, the larger the rescue effort would be required to get people safely to land”, Humpert told me.

Just a few years ago, the Costa Concordia disaster made it clear to a lot of people that modern cruise ship tourism has a lot more risks than we might have thought. So what if something like that took place in the remote regions around Spitzbergen or Greenland, where cruise tourism has been increasing, or even in the Northwest Passage? Humpert describes that as “a very horrifying scenario to think about.”

The Arctic is not the Med

“The Costa Concordia was – half a mile or a mile offshore in the Mediterranean, one of the most frequented cruise ship lanes in the world, and even there it took over 50 lives. In the Arctic, if you’re looking at a ship with 1800 people, first of all you’re not in the Mediterranean where waters are rather temperate, and where you have calm seas most of the time. In the Arctic most likely if something goes wrong it’s not going to go wrong on a nice sunny day with 5 degrees Centigrade, it’s probably going to go wrong in really harsh conditions, and suddenly you have a ship with 1500 to 1800 people, most of the people probably elderly, in frigid waters. The largest communities are probably smaller than the amount of people on the vessel itself and even if you have a helicopter or two on standby, how long is it going to take to get those people off the ship?”

Humpert also mentioned an incident involving the “Clipper Adventurer”, which ran aground in the Canadian Arctic on an uncharted rock in 2010. Fortunately, it happened in shallow water, just about three and a half meters deep, Humpert says. “They had the fortunate circumstances that they had time to get people into rubber dinghies and get them to shore. But of course if you’re looking at 1500 to 1800 people, that’s a whole different dimension”, he stressed again.

Of course certain precautions can be taken.

Cruising between the icebergs on Greenland’s west coast is a popular tourist attraction (I. Quaile, Ilulissat )

“The Danish coastguard along the west coast of Greenland requires cruise ships that go into Disko Bay and Iceberg Ally on the west side to go in pairs. They have to stay within a certain distance of each other when they go into ice-infested waters , just so there is actually a second floating platform that could take aboard these people if one of the cruise ships were to get into trouble. That in my opinion is one of the largest risks. Yes, you can have all the equipment on standby, you can have ice pilots along, but if something does go wrong and you need to get people off the ship quickly – the quickly part is the problem. And where do you put those people?”

Too big to sink?

With all of this, the problem is the huge size of today’s cruise ships. The thought of almost a thousand people converging on a small, remote Arctic community is one I personally find most unattractive. (That is an example of the British art of understatement.) Humpert stresses even when cruise ships go into regular ports, they have to take people ashore in groups.

With this first trip by a giant liner through the Northwest Passage, he reckons all possible precautions will be taken. But if the voyage works well, the danger is that more and more companies will want to follow suit and send large vessels up there.

“Then suddenly we might have lower budget cruises that don’t take the necessary precautions. With higher frequencies of these voyages, the risks definitely go up.”

After this record warm winter and the huge decline in the amount of sea ice in some regions of the Arctic, my feeling is that people can be lulled into a false sense of security, when they hear about a “warming Arctic”. Malte Humpert agrees.

“Whenever people read in the headlines “ice-free Arctic,” it kind of makes it sound like the Arctic is now your local pool or the Mediterranean, suddenly. The Arctic is still a very harsh environment. Just because the ice is melting during the very short summer season and because of this “warming” – that does not mean its suddenly warm – it’s still a very harsh environment and you forget that small mistakes in the Arctic can rather quickly become very deadly mistakes.”

The highest risk, according to the Arctic expert, is that people forget that a cruise in the Arctic can be a dangerous endeavor. “If everything goes well it would probably be the experience of a lifetime, but small errors can quickly become insurmountable in the Arctic”.

Northwest Passage – international waters

When it comes to regulating shipping in the region, Humpert notes that the Northwest Passage is considered an international strait. That means as long as commercial vessels or cruise ships have international certificates of transit, they are allowed to go through.

“Canada can require that vessels abide by environmental regulations, that they take on board ice pilots, the coast guard can prescribe certain routes. If they see that some channels along the Northwest Passage have too much ice, they can require cruise ship to go a different route. But in general, the Northwest Passage is accessible to anyone. And of course the more activity you have, the harder it becomes to ensure that environmental regulations are abided by, that accidental spills or other mishaps don’t occur in the Arctic, and so its a very careful balance between allowing these first business ventures to head up into the Arctic and at the same time fulfilling these pledges we have seen over the last five to ten years that the Arctic is a pristine environment and should be protected”.

I am deeply concerned that climate change is opening the Arctic so fast that it’s hard for environmental protection and safety measures to keep pace. Humpert says it’s always difficult for policymakers to keep up in cases like this. But he is full of praise for the oil spill and search and rescue agreements drawn up by the Arctic Council. The question is whether the assets and infrastructure are there to implement them. Icebreakers???

The cheap fuel paradox

Aside from the issue of cruise ship traffic, international freight companies have used the Northern Sea Route along the Russian coast in recent years to transport gas and commodities, reducing the distance between Shanghai and Hamburg by around 6,400 kilometers compared with the Suez Canal Route. .

Humpert’s Arctic Institute recently conducted a study on the feasibility of the Northern Sea Route for different types of shipping, compared with the other route.

The study includes a calculator, in the form of an online tool, and allows for variables such as vessel size, ice class, distance, ice extent, fuel price, average speed, NSR fees, etc., to give a very detailed calculation of what type of transport would be economically feasible. The tool illustrates how cost curves change depending on the amount of ice, size of the vessel and the price of fuel. The calculator even takes into account ship hull designs to calculate costs.

“In 2012 and in 2013 we saw quite a bit of traffic going through the Northern Sea Route, about 70 ships in 2013 was the peak. That’s still very small compared what goes through the Suez Canal, where we see around 16, 17, 18,000 ships passing through a year. What our study in cooperation with the Copenhagen Business School Maritime Center shows, is that the key factor is fuel prices. So if fuel prices are very low then those shortcuts don’t really pay dividend for shipping companies”, Humpert told me.

I was quite shocked by one fact he drew my attention to. At the moment oil prices are so low that a lot of shipping companies are choosing not to go through the Suez Canal any more. Instead, they take the long way round, choosing to go around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. Humpert says this adds 3500 miles to their journey and about 10 or 11 days of sailing time. It seems that they still save about 350,000 dollars on average by not paying transit fees for the Suez Canal.

The environmental and climate costs of the extra fuel burned clearly just do not feature!

This also has implications for the Northern Sea Route, says Humpert.

“You need special insurance, you need ice breaker escorts which are quite costly, you need to pay transit fees to the Northern Sea Route Administration. So it’s an interesting calculation”. The experts come to the conclusion that sometimes, for some shipping operators, at some time of year or in a given year when certain conditions are right, it may be economically feasible to go through the Northern Sea Route. At other times it may be more prudent or more economical to use the Suez Canal.

“Currently, the Northern Sea Route is a very specialized shipping environment. Very few operators have looked at it, and those that tried in 2013 haven’t really come back. Last year we only saw 19 ships go through the Northern Sea Route and very, very limited cargo volumes. It will be interesting to see what happens this year as we have a new record ice low in January and February. It could be that we are heading for that kind of ice-free season where two or three months of the year you really have a practically ice-free Northern Sea Route, which would start to alter the economic calculations. But the fuel price would certainly have to be higher”.

So we seem to be caught in some kind of a vicious circle. If the fuel price stays low, the Arctic will be saved for some time from increased freight traffic along the Northern Sea Route. But the price is increased emissions from the burning of all that extra cheap fuel. And that, as we know, heats up the climate further and melts ice, making it easier for shipping of whatever form to head into Arctic waters. If the fuel price goes up, companies will be keener to make use of the shorter Northern Sea Route. Unless there is some kind of miraculous, unexpected planetary cool-down somewhere in the pipeline, I can only conclude that increased shipping and the risk of a potentially catastrophic oil-spill or other incident in Arctic waters are only a matter of time.

Arctic winter: warm, wet, weird

Here in Germany, the winter has seemed strange enough. We had flowers in bloom at Christmas, and people sneezing with pollen allergies. Overall it was extremely mild. Now we are just having the odd flurry of sleet, with the magnolias getting ready to bloom and much of nature said to be three weeks ahead of schedule. But that is nothing compared to what’s been going on in the Arctic.

“The Old Normal is Gone”, is the headline of a piece on Slate by Eric Holthaus, sub-headed “February Shatters Global Temperature Records”. He says the record warmth is so dramatic he is prepared to comment using unofficial data, before the official data comes out mid-March. February 2016, he says was probably somewhere between 1.15 and 1.4 degrees Celsius warmer than the long-term average, and about 0.2 degrees above last month, which was itself a record-breaker. This, Holthaus calculates, means while it took us from the start of industrialization until last October to reach the first 1 degree C. of warming, we have now gone up an extra 0.4 degrees in just five months. Paris target 1.5 degrees maximum – here we come!

In the Arctic, this is particularly dramatic. Parts of the Arctic were more than 16 degrees Celsius warmer than “normal” for the month of February, which, Holthaus says, is more like June temperatures, although it would normally be the coldest month.

Svalbard, one of my favourite icy places, has averaged 10 degrees Celsius above normal this winter, with temperatures rising above the freezing mark on nearly two dozen days since December first.

Correspondingly, the Arctic sea ice has reached a record low maximum. Lars Fischer, writing in the German publication Spektrum der Wissenschaft, notes that January already saw the smallest ice growth of the last ten years. In mid-February, he writes, satellite data showed the ice cover in some parts of the high north was almost a quarter of a million square kilometers less than ever before on this date. This lasted two weeks, than the ice grew a little last week, to draw equal with the previous all time low for a first of March. New ice will be much thinner than the old multi-year ice, a trend that has been increasing.

New satellite data

Researchers are using a new technique to gain data about the thinning ice pack in real time. An article in Nature, “Speedier Arctic data as warm winter shrinks sea ice”, describes a new tool to track changes as they happen and provide near real time estimates of ice thickness from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 satellite. Previously, there was a time lag of at least a month.

Satellite data is revolutionizing what we know about the Arctic ice. The news is not good. (Pic. I.Quaile, Tromso)

Natural fluctuation, el Nino or human-made climate change?

Of course there are those who say fluctuation is natural in the Arctic. But this year, this fluctuation is extreme. Some researchers say the melt season started a whole month too early. Certainly, at this time, the Arctic should be in the grip of winter.

Fischer titles his article “Absurd winter in the Arctic”. I’m not sure absurd is the best way of describing it. (It could actually seem quite logical if you look at the extent of extra warmth we have been creating with our greenhouse gas emissions). Looking at an article in the Independent by Geoffrey Lean, I see the term “absurdly warm”comes from the NSIDC, National Snow and Ice Data Centre in Boulder, Colorado. The “strangest ever” and “off the chart” are used by NSIDC director Mark Serreze and NOOA respectively. Those figure.

In December 2015, the high Arctic experienced a heatwave. We saw temperatures near the North Pole going above freezing point. January was the warmest month since the beginning of weather data. In February, parts of the Arctic were more than ten degrees warmer than the long-term average.

The Arctic Oscillation is partly to blame. It is currently such that warm air can make its way north. Strong Atlantic storms have been pressing the warm, moist air north into the High Arctic. But surely there can be no doubt that our human-made climate warming is playing a major role in all this?

It remains to be seen how the situation will develop as the spring sets in. Fisher notes that the last winter ice maximum extent was very low, but was not followed by a new record low in summer.

Eric Holthaus notes that although we are experiencing a record-setting El Nino, which “tends to boost global temperatures for as much as six or eight months beyond its wintertime peak”, this alone cannot be responsible for the temperature records.

He quotes scientific studies indicating that El Nino’s influence on global temperatures as a whole is likely small, and that its influence on the Arctic still isn’t well known.

“So what’s actually happening now is the liberation of nearly two decades’ worth of global warming energy that’s been stored in the oceans since the last major El Nino in 1998”, he writes.

“The old normal is gone”

Whatever the cause – this record warmth is a major event in our climate system. Holthaus quotes Peter Gleick, a climate scientist at the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California in his article title: “The old normal is gone”. “The old assumptions about what was normal are being tossed out the window”.

“We could now be right in the heart of a decade or more surge in global warming that could kick off a series of tipping points with far-reaching implications”, says Holthaus. Where have I heard this before?

Lean, in the independent, says two new studies by the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts give new evidence of self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms. This is not new. How much more evidence do we need? Permafrost thaws, resulting in emissions of methane and CO2 from the soil. Melting ice means the reflective white surface is replaced by dark water, which absorbs heat.

So what are we doing about it? In interviews with experts from NGOs including Earthwatch and Germanwatch recently, various experts have been confirming my own feeling that the Paris Climate Agreement may have been a milestone, but not necessarily a turning point – unless climate action is taken very quickly.

I would like to be optimistic. But there is so much evidence suggesting that whatever we do, it is likely to come too late to save the Arctic as we know – knew – it for coming generations. Come on world, prove me wrong! Please!

Unbaking Alaska?

When I first went to Alaska in 2008, “Unbaking Alaska“ was the title of the reporting project on how climate change is affecting the region and what the world might be able to do about it. I had to explain the title to my German colleagues, unfamiliar with the “Baked Alaska” dessert, while my North American and British colleagues thought it was a quirky, witty little title.

This week, when I saw an article in the Washington Post entitled “As the Arctic roasts, Alaska bakes in one of its warmest winters ever”, I found the “dessert” had become a little stale .

The thing about “Baked Alaska” is that the ice cream stays cold inside its insulating layer of meringue. Unfortunately, all the information coming out of Alaska and the Arctic in general at the moment, suggest that the ice is definitely not staying frozen.

Too hot for comfort?

In the Washington Post article, Jason Samenow refers to this winter’s “shocking warmth” in the Arctic, some seven degrees above average. Alaska’s temperature, he says, has averaged about 10 degrees above normal, ranking third warmest in records that date back to 1925. Anchorage has found itself with a lack of snow.

“This year’s strong El Nino event, and the associated warmth of the Pacific ocean, is likely partly to blame, along with the cyclical Pacific Decadal Oscillation – which is in its warm phase”, Samenow writes. Lurking in the background is that CO2 we have been pumping out into the atmosphere over the last 100 years or so.

Sea ice on the wane?

Meanwhile, the Arctic sea ice is at a record low. Normally, in the Arctic, the ocean water keeps freezing through the entire winter, creating ice that reaches its maximum extent just before the melt starts in the spring. Not this time.

Yereth Rosen wrote on ADN on Feb. 24th the sea ice had stopped growing for two weeks as of Tuesday. He quotes the NSIDC as saying the ice hit a winter maximum on February 9th and has stalled since.

“If there is no more growth, the Feb. 9 total extent would be a double record that would mean an unprecedented head start on the annual melt season that runs until fall”.

This would be the earliest and the lowest maximum ever. Normally, the ice extent reaches its maximum in early or mid-March.

The most notable lack of winter ice has been near Svalbard, one of my own favourite, icy places.

The experts say it’s too early to say whether this is “it” for this season. There is probably more winter to come. But even if more ice is able to form, it will be very thin.

Toast or sorbet?

Coming back to those culinary clichés: Samenow in the Washington post writes of the second “straight toasty winter” in the “Last Frontier”. The links below his online article are listed under “more baked Alaska”. Amongst them I find the headline: “As Alaska burns, Anchorage sets new records for heat and lack of snow” and “Record heat roasts parts of Alaska”.

The trouble comes when these catchy titles become clichés and somehow stop being quirky.

Don’t we run the risk of not doing justice to the serious threat climate change is posing to the most fragile regions of our planet? Sometimes I worry that the warming of the Arctic is becoming something people take for granted, and, even more dangerous, something we can’t do much about. At times I sense a cynicism creeping in.

I for one will be keeping my oven-baked cake and chilled ice cream separate this weekend.

Is it possible to un-bake Alaska? Food for thought.

Picture gallery on “Baked Alaska” expedition.

Feedback