Search Results for Tag: Svalbard

Arctic residents in hot water

At the swimming club last weekend, one of my fellow swimmers complained the water was too warm. She said she couldn’t swim at her usual speed when the temperature in the pool rose even a little bit. It left her feeling tired and lethargic. So how much more dramatic must it be for the tiny creatures at home in cold Arctic waters, when a warm influx changes their surroundings and living conditions.?

The warming of Arctic waters with climate change is likely to produce radical changes in the marine habitats of the High North. Data from long-term observations in the Fram Strait, which researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) have now analysed and published in the journal “Ecological Indicators”, confirms that even a short-term influx of warm water into the Arctic Ocean would suffice to fundamentally impact the local symbiotic communities, from the water’s surface down to the deep seas. They found that this happened between 2005 and 2008.

The deep sea observatory

Over the past 15 years, researchers from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for polar and marine science (AWI) have been keeping an eye on the sensitive marine ecosystem in the Fram Strait, the sea lane between Greenland and Svalbard .The institute operates a deep-sea observatory there, known as “HAUSGARTEN”, which translates literally as house garden. It is actually a network of 21 individual mini research stations. Every summer, scientists pay them a visit and collect water and soil samples. Some of the stations have anchored systems that operate year-round, recording the water temperature and tides, collecting water and soil samples at regular intervals, and capturing the sediments that drift down to the seafloor from the upper water layers.

“This is the only observatory of its kind in the world. There’s no other project in which readings from the surface down to the ocean floor were taken in fixed positions over such a long time – let alone in the polar regions,” says AWI biologist Thomas Soltwedel.

For the current publication, the AWI researcher and his team analysed the first 15 years of the HAUSGARTEN dataset. The Fram Strait is especially interesting for Soltwedel and his colleagues because it represents the only deep juncture in the Arctic Ocean, allowing water masses from the Atlantic to flow into the Arctic to the west of Svalbard. In turn, water and ice floes find their way back out of the Arctic Ocean on the strait’s Greenland side.

Too warm for comfort

Until now, the scientists say it was unclear just how polar marine organisms were responding to the warming of the ocean and shrinking sea-ice cover. Now, the long-term observations show that arctic marine habitats could change radically if subjected to a sustained rise in temperature. The AWI researchers say their most surprising finding is that the thermally induced changes at the ocean surface can rapidly spread to affect life in the deep seas.

Normally the water near the surface, which flows north out of the Atlantic through the Fram Strait, has an average temperature of three degrees Celsius. With the help of their observatory, the AWI researchers were able to establish that from 2005 to 2008 the average temperature of the inflowing water was one to two degrees higher: “In that time, large quantities of warmer water poured into the Arctic Ocean. Since polar organisms have adapted to living in constant cold, this extra heat input hit them like a temperature shock,” Soltwedel explains.

He says the reactions in the ecosystem were correspondingly extreme: “We were able to identify serious changes in various symbiotic communities, from microorganisms and algae to zooplankton.”

Migrating sea creatures

One major change described in the article was the increase in free-swimming conchs and amphipods, which are normally found in the more temperate and subpolar regions of the Atlantic. In contrast, the number of conchs and amphipods in the Arctic dropped significantly.

The researchers also noted a decline in small, hard-shelled diatoms. Prior to the unexpected influx of warm water, they made up roughly 70 per cent of the vegetable plankton in the Fram Strait. But during the warm phase, the foam algae Phaeocystis took their place. A change with consequences, Soltweder explains: “Unlike diatoms, foam algae tend to clump and sink to the ocean floor, where they become a food source. But the sudden rise in available food led to major changes in deep-sea life, including a noticeable increase in the settlement density of benthic organisms.”

If you are not a marine biologist, you may be wondering what that means for the future of the Arctic and why we should be concerned about it. The problem is that all of this affects the Arctic food web.

The scientists can’t say exactly how at this point. But, as with so many other aspects of climate change: “Above all, we’re troubled by the simple fact that the changes have been so rapid, and so far-reaching.”

New residents here to stay

Since the flow of warm water has subsided, the water temperature in the Fram Strait has stabilised – though it is still slightly above the average value from before 2005. Yet some of the changes appear to be there to stay. The conchs from the lower latitudes seem to have made a home for themselves in the Fram Strait.

As usual, the scientists are reluctant to say whether the warm-water influx they monitored is due to climate change or could be part of natural climate fluctuations. They say they need data covering several decades to be more certain.

But either way, the results of the ecological long-term studies clearly show that even short-term changes in ocean temperature can drastically impact life in the Arctic. So it looks like there will certainly be more to come, as the world continues to heat up.

Melting glacier risk to seabed ecosystem

On my first visit to the Arctic in 2007, I went out into the Kongsfjord at Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen, with some marine biologists working out of Koldewey station, run jointly by France and Germany. It was June, and the glaciers at the end of the fjord were just starting to thaw. While I was enjoying the blues, whites and greys of the sea, ice and sky, the researchers in the small boat got very excited when they saw the water turned brown, where sediment was flowing into the fjord from the retreating glacier.

“Who turned off the light up there”?

They had been waiting impatiently for the thaw to set in, because their research focus was on what that means for the life forms on the seabed, or benthos. Clearly, if you live down on the sea floor, the intrusion of brown mud and other sediment changes your surroundings. Not least, it means less light coming down from above. Now while a certain amount of that is going to happen naturally every year with the changing seasons, the question is: what happens if there is a big increase in sediment coming in because of increasing melt through climate change?

I was interested to hear about a study published this week in Science Advances, dealing with that same question in the Antarctic. The findings indicate that melting coastal glaciers are having an impact on the entire ecosystem on the seafloor, leading to a loss of biodiversity through sedimentation. The scientists were looking at the West Antarctic peninsula, where the temperature has risen almost five times faster than the global average in the last fifty years.

Global warming changes seafloor communities

The study, published by experts from Argentina, Germany and Great Britain, including the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI,) is based on repeated research dives. The scientists believe increased levels of suspended sediment in the water caused the dwindling biodiversity registered in the coastal region. They say it occurs when the effects of global warming lead glaciers near the coast to begin melting, discharging large quantities of sediment into the seawater.

To find out exactly how and to what extent the retreat of glaciers is affecting bottom-dwelling organisms, researchers at the Dallmann Laboratory are now mapping and analysing the benthos in Potter Cove, located on King George Island off the western Antarctic Peninsula. The lab is operated by the Alfred Wegener Institute and the Argentine Antarctic Institute (IAA) as part of the Argentinian Carlini Station. Researchers have been monitoring benthic flora and fauna there for more than two decades.

In 1998, 2004 and 2010, divers photographed the species communities at three different points and at different water depths: the first, near the glacier’s edge; the second, an area less directly influenced by the glacier; and the third, in the cove’s minimally affected outer edge. They also recorded the sedimentation rates, water temperatures and other oceanographic parameters at the respective stations, so that they could correlate the biological data with these values. Their findings: some species are extremely sensitive to higher sedimentation rates.

Short sea squirts adapt better

Sea squirts are small invertebrate creatures that live on the sea floor and feed by filtering the water through their anatomies.

“Particularly tall-growing ascidians like some previously dominant sea squirt species can’t adapt to the changed conditions and die out, while their shorter relatives can readily accommodate the cloudy water and sediment cover,” says Dr Doris Abele, an AWI biologist and co-author of the study. She is worried that “the loss of important species is changing the coastal ecosystems and their highly productive food webs, and we still can’t predict the long-term consequences.”

Can Arctic marine biologists work fast enough to keep up with climate change? (Ny Alesund, Pic: I.Quaile)

As with so many aspects of our oceans, there is a lack of base data on how sediment from melting glaciers affects the numerous life forms on the seabed.

“It was essential to have a basis of initial data, which we could use for comparison with the changes. In the Southern Ocean we began this work comparatively late,” says the study’s first author, marine ecologist Ricardo Sahade from the University of Cordoba and Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council CONICET, who is leading the benthic long-term series. “Combining this series of observations, accompanying ecological research on important Antarctic species, and mathematical modelling allows us to forecast the changes to the ecosystem in future scenarios,” says co-author Fernando Momo from Argentina’s National University of General Sarmiento.

With scientists telling us the ice of the West Antarctic peninsula has already passed a tipping point, the question is whether scientific monitoring and research will be able to keep pace with the rapid rate at which climate warming is already having major impacts on our oceans. For many species of our seabottom-dwelling creatures, the slow pace of greenhouse gas emissions reductions may well come far too late.

See also: Antarctic glaciers retreat unstoppable

Arctic plastic “garbage patches”

There are a lot of things you might want to discover on a research cruise in the Arctic. Chunks of plastic floating around are not amongst them. But that is just what biologist Melanie Bergmann and her colleagues from the Alfred-Wegener-Institute and the Belgian Laboratory for Polar Ecology repeatedly did find while they were cruising through the Fram Strait, between Greenland and Svalbard.

They have just published a study documenting that plastic garbage has even reached the far north of the planet. In the online portal of the magazine Polar Biology, they describe how they found plastic waste floating on the surface of the ocean.

Plastic pollution – a fact of life?

In 2012, Bergmann and her colleagues took the opportunity of joining a cruise on the German research ship Polarstern to the Fram Strait to measure the extent of plastic pollution there. They monitored the ocean surface from the boat and a helicopter. Over 5,600 kilometres they found 31 pieces of plastic rubbish. But that will only be the tip of the “garbage-berg”.

“Since we were counting from the bridge of the ship, which is 18 metres above the sea surface, or from the helicopter, we primarily found large pieces of flotsam”, Bergmann told journalists. “So our figures very probably under-estimate the actual amount of garbage”, she added.

Too beautiful to “waste”? The team even found plastic waste in Greenland’s Ice Fjord (Pic: I. Quaile, Ilulissat)

Plastic waste tends to disintegrate into small pieces, just one or two centimeters in size, if they float in the sea for any length of time.

Somehow, the results of this study did not really surprise me. That, I think, is a very sad state of affairs. There have been so many reports of plastic particles being found in animals and birds and so in our human food chain that there is a danger we take this serious form of pollution for granted. The ngo Ocean Care estimates that around nine million tons of plastic waste finds its way into the oceans every year.

The seabed as a waste dump?

The AWI scientists say this is actually the first study to show that plastic waste is floating around on the surface of Arctic waters. For an earlier study, the German biologist searched for plastic, glass and other waste on photos taken of the Arctic seabed. She found that even in deep sea areas, the amount of garbage has increased in recent years. The concentration is 10 to 100 times higher than on the surface. The experts deduce from this that garbage ultimately sinks to the bottom and collects there.

Plastic bag at the HAUSGARTEN, the deepsea observatory of the Alfred Wegener Institute in the Fram Strait. This image was taken by the OFOS camera system in a depth of 2500 m. Photo: Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Melanie Bergmann/OFOS

The question is: how does this waste get up into the Arctic? It could, it seems be part of what, is described as a “garbage patch”, created when plastic waste gets caught up in ocean currents and concentrated into a kind of whirlpool.

Scientists have already identified five of these patches around the globe. The waste in the Arctic appears to be part of a new, sixth “patch” developing in the Barents Sea. What a depressing development! Scientist Melanie Bergman thinks it probably contains waste from the densely populated coastal regions of northern Europe.

“It is thinkable, that some of this garbage drifts north and northwest, as far as the Fram Strait”, she says. Another theory, she says, it that the garbage being found in the Arctic is caused by the retreat of sea ice.

“More and more fish trawlers are following cod further north. Presumably, rubbish from the ships ends up in Arctic waters, either deliberately or by accident. We are assuming that this trend will continue”, says Bergmann.

Climate change and pollution threat

So while here in Bonn, just across the road from my office, the UN climate secretariat is struggling to come up with a draft text for the Paris COP21 summit, which will be acceptable to all parties (and so subject to so many compromises and loopholes?), we have yet another sign of a climate change impact on the no-longer-pristine Arctic. And at the same time, it indicates the effects our unsustainable lifestyles are having on the environment of the planet. I have been witness to many arguments over whether governments should put more effort into combating climate change or environmental degradation and pollution. Ultimately, once more I come to the conclusion that it is virtually impossible to separate the two.

Last week I interviewed two experts on different aspects of ocean protection for a Living Planet special: Oceans under Pressure. They expressed similar views on the intrinsic connections between climate change, humans’ maltreatment of the environment and the health of the oceans on which we rely for survival. Not only are we causing climate change. The other pressures we put on the oceans make it less able to cope.

Tony Long is in charge of work against illegal fishing with Pew Charitable Trusts:

“I think climate change, over-fishing and illegal fishing are all linked in one way or another. The bad practices that occur from illegal fishing can damage the ecosystem, whether it be trawling and ripping up corals, or fishing the wrong species at the wrong time. It all has an effect on the broader ecosystem. And with ocean acidification and the changes that are taking place now scientifically proven, that’s going to reduce the amount of fish people can catch, if we don’t start to look after it. So actually it should all be seen as one”. (Read the interview here).

Ove Hoegh-Guldberg is Director of the Global Change Institute at the University of Queensland, Australian, and chief scientist with the XL Catlin Seaview Survey, which has been monitoring the state of the world’s coral reefs, including the current global bleaching event:

“On our current track where we’re polluting local water, we’re overfishing coral reefs and now we’re rapidly changing the temperature and acidity of the ocean, we won’t have coral reefs and it will be a very long time before they come back – probably well after our exit from the climate. We are the first generation to see these types of impact and we are going to be the last that has the chance to do something. We must get to very low CO2 emission rates as soon as possible, hopefully over the next 20 to 30 years. Because if we don’t – it won’t just be coral reefs. It will be a large number of other ecosystems that go, and humanity will be in trouble.” (Read the interview here.)

I rest my case.

Arctic Winter Impressions

Your Iceblogger is off on a hard-earned break for the next few weeks. I’d like to leave you with some photographic impressions of my winter trip to the Arctic. Thanks again to Norway’s Arctic University in Tromso and the organisers of Arctic Frontiers for the opportunity to visit Svalbard and Tromso at this fascinating time of year. Look out for the next post in April, when spring should be well underway.

Ice floats in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard

Svalbard twilight

- Icicles on the nets aboard the Helmer Hanssen

Winter light outside Tromso

Norway’s Polar Satellite Centre

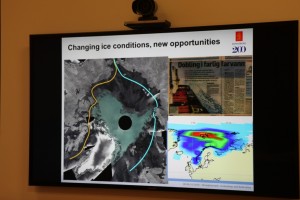

Polar orbit satellites monitor what’s happening at the ends of the planet – and, of course, the regions in between. Ice conditions, land movement, shipping, pollution – but how does that information actually make its way to the scientists and authorities who evaluate it and use it as a basis for all kinds of decisions?

During my recent visit to Arctic Norway, I had the chance to visit a facility that plays a key role in collecting and disseminating satellite data on the polar regions. On the outskirts of Tromso, Norway’s “Gateway to the Arctic”, there is a satellite ground station, run by KSat, or Kongsberg Satellite Services AS. It is a Norwegian commercial company which provides ground station and earth observation services for polar orbiting satellites. With three interconnected polar ground stations: Tromsø at 69°N, Svalbard (SvalSat) at 78°N and Antarctic TrollSat Station at 72°S, combined with a mid-latitude network of stations in South Africa, Dubai, Singapore and Mauritius, KSAT operates over 70 antennae positioned for access to polar and geostationary orbits.

The Tromso station has contact to 85 satellites every day, and every month the station monitors some 15,000 passes of these satellites overhead.

High demand for high-tech service

High demand for high-tech service

When it comes to which businesses stand to gain from climate change, the providers of satellite data have to rank high on the list. There is a huge demand for data from space, and KSat, it seems, is the biggest company worldwide carrying out this kind of activity.

While I was in town for the Arctic Frontiers conference, two colleagues and I were shown the facility on a beautiful wintry Saturday morning by Jan Petter Pedersen, the Vice President of the company, who is responsible for developing products to expand the business. He studied physics in Tromso and got into satellites during that time, he told us, going on to a PHD in remote sensing. Pedersen has been at KSat for 20 years and says the technology has come a long way in that time. These days, it’s all about remote control via pcs.

We tend to take satellite data for granted. But if you think about it, somebody has to pick up the masses of data from all those satellites circling over the poles and pass the appropriate images to those who need them. Energy, environment, security – these are key areas which make use of the data. In the Tromso station, that data is provided to those who need it more or less in real-time. The company says it can get the data down and sent on to its destination anywhere in the world within 20 minutes. So if you want to detect an oil spill in – say – the Gulf of Mexico? – The chances are, you will get information from this Arctic town.

Some companies own and operate their own satellites, and distribute the data. KSat doesn’t own any satellites, but has agreements to use data. They can access radio data from almost all satellites in operation today.

The USA and Canada are the biggest market for the company’s services, says Pedersen. Then comes Europe, followed by Asia.

The world’s largest polar ground station is the one on the Arctic island of Svalbard. I wasn’t able to visit it during my winter trip – put it must be pretty impressive, with more than 30 antennae.

Satellite monitoring as deterrent to polluters?

When it comes to oil spill detection or monitoring, satellite images play a key role.

Optical sensors have limitations in bad weather, so radar satellite data are of key importance, Pedersen explains. Oil spill detection is the most important of KSat’s earth observation activities. EMSO (European marine Safety Agency) in Lisbon is responsible for European oil spill detection. They get satellite data from 4 providers of satellite data, of which KSat is the biggest. It covers 60% of the waters from the Barents Sea to the Bay of Biscay and the Baltic.

In 2008 there were 10.77 possible reported spills per million km2. In 2011, this was down to 5.08, Pedersen told us. I asked why they talk of “possible”. It seems it is not always possible to be 100 percent sure what the satellite detects is an oil spill. The reliability is somewhere over 60 percent. Pedersen believes the satellite service plays a role in decreasing the figure. As it becomes increasingly well known that satellites are observing and collecting the data, there is a higher awareness that oil spills are being detected. Presumably this is a deterrent to deliberate discharges of oil as well as a key source of information on accidents.

From pirates to icebergs

Another key use for satellite data is in monitoring ship traffic, including detecting, tracking and identifying vessels. This means the authorities can spot illegal activities and inform the coast guards. This helps in finding pirates, for instance.

Tracking icebergs and monitoring ice development have also been aided by the growing availability of satellite data. The NSIDC is one of KSat’s most important customers. They need the data to map the extent and condition of the ice.

Satellite data shows ice changes.

Ships frozen into the ice for research purposes such as the Lance, use satellite images via Tromso. Many other ships use them to chart a course when operating in ice.

Monitoring fishing activities, offshore oil exploration, tracking land movement – all these activities rely on satellite information today.

Pedersen told us the Norwegian capital Oslo is sinking at a rate of 2 cm a year. He also mentioned a landslide risk area outside of Tromso, where a mountain is sliding into the ocean. Ultimately, it will go into the fjord and create a tsunami effect, says Pedersen. That would endanger the settlement. It is moving at 15mm per year. The satellites are keeping an electronic eye on it.

Norway, incidentally, is the country with the highest use of data per person. Most of it is maritime. So it seems fitting that the country should be the location of some of the world’s most important ground stations. There is more to the picturesque Arctic harbour town of Tromso than meets the eye – I can tell you that even without satellite data!

Feedback