Search Results for Tag: Svalbard

A good haul for polar night team

The Polar Night cruise will come to an end on Tuesday, when the last of the scientists will leave the ship with their samples. I was able to stay until the end of the week, when I left the ship at Ny Alesund with some of the researchers, who were changing places with colleagues. I have left Svalbard, but not the Arctic. More about my current whereabouts later.

A good haul in the polar night

It was interesting to hear that our scientists were happy with their “catch”. Sören Häfke, the German scientist from the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, had more than enough of the little crustaceans calanus finmarchius. When they get back to Germany, they can start their genetic analysis to find how their biological clock works in the dark, Arctic winter. In summer, it is assumed light tells them when to come to the surface to feed and when to go down deeper to avoid predators. But what happens in winter, when it is dark all day long? I will look forward to hearing what they find out.

The Russian team had plenty of interesting sediment samples to look into. The others on board also seemed to be happy with the plankton, crustaceans and small fish they brought in for further research. Marine Cusa was a bit unhappy about the lack of polar cod in the fjord. There seemed to be no shortage of larger Atlantic cod. This is related to the amount of Atlantic water currently present in the fjord, expedition leader Stig Falk-Petersen explained to me. It looks as if Marine will be changing the subject of her Master’s thesis. But I have the feeling it will be no less interesting.

“Life doesn’t stop when the light goes out”

Paul Renaud, a Professor at the University Centre in Svalbard, coordinated the logistics of the expedition on board as well as conducting his own biological research. He is one of those who came up with this Polar Night project. As he sums it up, there is a need to follow up on the few studies done in the last ten years which indicate that there is much more activity in the Arctic ocean in winter than previously thought. This must be triggered by processes other than light. Light is critical for the functioning of the ecosystem, but “it’s not that when the light goes out, everything stops functioning”, Paul told me.

From the samples I was shown under the microscope, I can confirm that there is indeed plenty of life going on. And many of the creatures were carrying eggs.

Climate paradox: easier access – shifting parameters

I asked Paul what was driving the surge of research into the Arctic winter. Firstly, new technology makes it possible to take measurements under the ice, and all year round, when there is no-one up here, he explains. Buoys tethered to the ice are one example. A series of permanent observatories has also been set up in the fjords here, measuring temperature, salinity, oxygen, light, chlorophyll and the movement of plankton. The number of research stations in the region has also increased.

The other major factor is quite clearly climate change. The absence of ice makes it much easier to sail up here, says Paul. Just 20 years ago, this fjord would have been completely covered with ice at this time. Now the sea ice is only found in the far reaches of the fjord. But Paul confirmed my theory that while warming is making access easier, it is also changing the parameters the scientists want to measure. “We are addressing a moving target”, is how he describes it.

Ice, less ice, no ice?

When it comes to forecasting how the Arctic ocean and its ecosystem will react to climate change in the long term, the scientists here say we desperately need more data. The IPCC gives around ten scenarios for how climate in the Arctic could develop, Paul explains. Clearly, if we can rely on predictions that the Arctic will be ice-free in summer from the middle of the century at the latest, that will have certain effects on ecosystems

Some organisms can be very flexible, says Renaud, not breeding for ten years and still continuing their populations. But short-lived organisms that rely on a certain timing of ice or live in the sea ice may well be more seriously affected. But without more information, it is impossible to tell how they will react in the long term.

Along with climate change, increased development is bringing more changes to this once inaccessible region, as discussed many times here on the Ice Blog and in my articles for dw.de. Paul is involved in developing monitoring practices. He stresses this is new territory for economic activities like oil exploration, fisheries, tourism and shipping, and that we urgently need more data on the effect of these activities on sensitive components of the Arctic ecosystems.

Can science keep pace with development?

One question I seek the answer to when I talk to Arctic experts is: can this research keep pace with the speed of the development? The answer depends partly, of course, on how fast that development will be. The Svalbard expert says there will still be sea ice in the Arctic in winter for the foreseeable future, around 100-150 years. That will slow economic activities like oil and gas exploration. “That buys us a little more time”, says the marine biologist. But he sees a huge challenge to identify and monitor the impacts of rapidly growing activities like tourism and shipping.

As I packed up to prepare to leave the Helmer Hanssen at the Ny Alesund research station, Paul was giving his instructions to the scientific team. Some were leaving with me, others staying on for the next section. Coordinating the cleaning of the laboratory and deck areas still well splattered with mud, then the packing up and labeling of the samples and equipment, is a major operation. I thought it better not to whinge about fitting my cameras, recorders and Arctic gear into their bags, which somehow seemed to have shrunk over the past week.

On our last night in dock at Ny Alesund, we were treated (not for the first time this week) to some northern lights, eerily dancing across the black Arctic sky. A wicked wind bit at our faces as we headed once again for the world’s northernmost marine lab. The researchers brought crates of samples. I myself brought a treasure trove of stories, ready to go online. The Arctic in winter is harsh but has a charm of its own. It was fascinating to experience the Polar Night, but I was looking forward to my next Arctic destination a bit further south, venue for the major Arctic conference: Arctic Frontiers.

I am now in Tromso, Norway’s “Arctic capital”, where the sun will be reappearing above the horizon this week and the magic pink, pale blue, silvery grey and white Arctic light is already in evidence for several hours a day.

How adaptable are Arctic ecosystems?

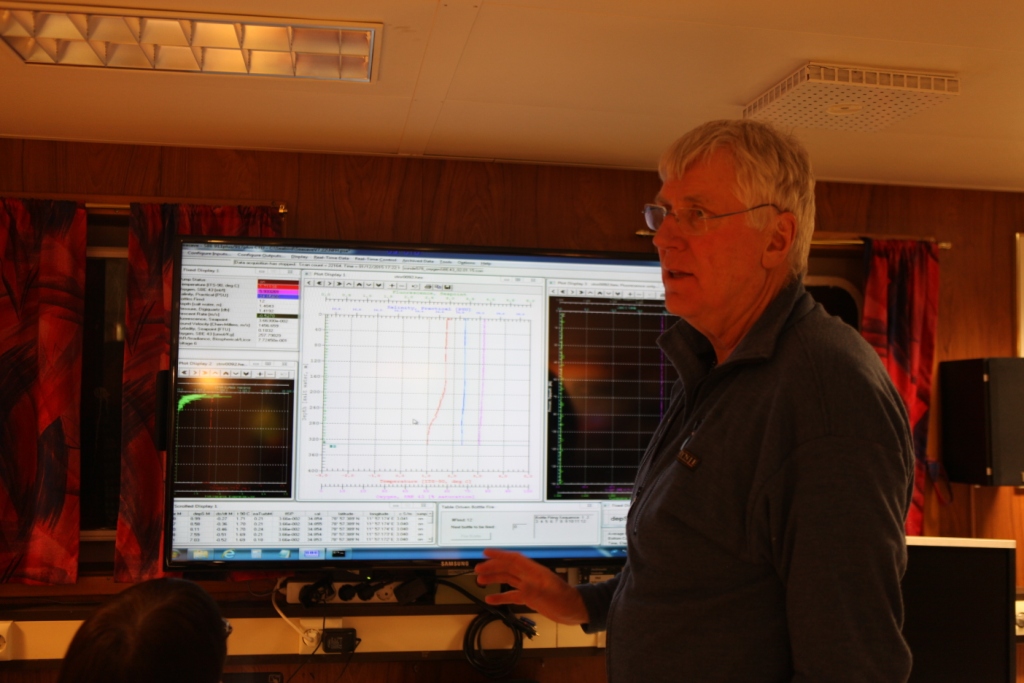

The man in charge of this scientific cruise is Stig Falk-Petersen, Professor at the Arctic University of Norway in Tromso and research advisor at Akvaplan-niva, a research consultancy working on environment monitoring. Originally from the Lofoten islands, he is a fountain of knowledge on marine life but also on history, especially relating to changes in the Arctic and indeed the European climate in general. He makes climate history of warm and cold periods more understandable by relating it to events like the Napoleonic wars, or the battle of Stalingrad. He stresses how that kind of approach shows just how important the climate is to society. He also knows a lot about the history of Arctic research. We owe a lot to Russia, where most of the Arctic research came from for a long time, says Stig.

Filling the winter gaps

I had a long talk with him, getting the background to this whole Polar Night project, which started in 2012. Apart from Nansen’s famous ice drift with the Fram (currently being repeated, but that’s a story for later), and the Russian North Pole drift stations, there had been few expeditions to the Arctic ocean in winter. Especially with regard to the southern part of the Arctic Ocean and the Fram strait, there were (and still are) huge gaps in our knowledge, Stig told me. In 2012 conditions were right for winter expeditions to the north and north west of Svalbard, to study the ecosystems. This was to complement a set of permanent observatories set up in the fjords here, measuring temperature, salinity, oxygen, light, chlorophyll and the movement of plankton.

Easier access through climate change?

I wanted to know why this has become possible. Is it because of climate change? Stig told me we actually have a climate record from 1550 until today about the ice around Spitsbergen, going back to accounts of Dutch whalers, which cover around 150 years, then to British expeditions. Since 1979 we have satellite records. All of this shows a large variation in the ice cover. Around 1680, he says, the whole of Spitsbergen was actually ice free. This lasted until 1800, when the ice expanded again from 82 degrees north to 76 degrees north – a huge and fast expansion of the ice cap. Then all this area was ice cold until approximately 1939. Since the year 2000, the region where we are now has been open again. “So you have this large variation of ice cover, driven by various climate factors, – temperature, pressure system, and that means a dramatic change for animals living in this area”, says Stig. To him, this shows the ecosystem up here is able to adapt to considerable change.

Ice, less ice, no ice?

“If you look back 50 years, this was all ice covered, so there was no primary production, so there were very few of these marine animals. Now, since the ice has retreated, the year 2000 approximately, we have a huge bloom of phytoplankton in the spring. So we have nutrients there, and we see that the calumus species, which is important for whales, is there. The bowhead whale, which was more or less extinct in this region for 150 years, is now back”. So, clearly, there are some winners – at least temporarily – in the course of climate change..

Our expedition leader was involved in one research project which could indicate that even some ice- dependent creatures have their own ways of coping with ice-free spells. He and his colleagues found that some tiny creatures which eat off the ice algae under the ice, float out with the ice. When it melts in summer in the Fram Strait, the egg-carrying females migrate down into the North Atlantic current, which then flows up into the Arctic Ocean, then migrate upwards in the water again. “Exactly when the ice algae blooms, in March April, their offspring is back and feeding again,” says Stig. So does that indicate that ecosystems here in the Arctic are well able to adapt to large variations in the climate, I want to know. Stig is reluctant to make anything that could be interpreted as a prediction of what future climate change could hold in store for the High North. But he stresses the temperature has increased in the Arctic by 2 degrees since 1987, much higher than the global increase. His impression is that the ecosystem has adapted well even to such a huge change in a short period. He doesn’t see himself as an optimist. But this view is certainly more optimistic than a lot of other people I talk to about the Arctic.

Locked up with deep-breathing krill

This morning started with a kind of international incident. My fellow Brit Carl Ballantyne and I were horrified to see our expedition leader Stig put sugar on his black pudding at breakfast. These trips are, of course, very international. With scientists from Norway, Russia, Poland, the UK, Germany and other countries on board, there is plenty of scope for “intercultural exchange”, although I still prefer my black pudding straight and spicy.

In between times, I found myself earning my passage on the Helmer Hanssen, working briefly – believe it or not – in the fridge with a load of krill! As the scientists work in shifts through the night and sleep when they get a chance, Carl was having trouble finding an assistant to help him note down his hourly measurements. He is monitoring the respiration of krill samples. So I found myself putting on a head torch and going into the dark fridge with a list and a pencil.

Carl is checking the respiration of certain species, mainly krill. They are living in little bottles of sea water. He puts a tube in to measure how much oxygen they are consuming, the figure appears on the computer and gets entered by hand in a notebook. That was my job. So what is this all about, I wanted to know. Again, it is all about finding out what creatures are up to in the water during these dark winter months. In summer, there is lots of respiration, Carl tells me, compared to winter. It has generally been assumed that since it’s colder and darker and there is not much phytoplankton for them to eat, they will not be feeding and so not using up much energy, which shows in the respiration. But now scientists have found that even at this time of year they are migrating vertically, that is moving up and down in the water column, so they must be using energy. Carl and co. want to find out more. Again, this is an area where not much research has been carried out in winter until fairly recently. These people really have the chance to find out things nobody knew before. Fascinating. And the iceblogger had the chance to make a tiny contribution!

Ice and mud, glorious mud

Most of the time our ship is out of range of internet connectivity, so this post will be delivered to you from the research base Ny Alesund. My hosts and the station staff were kind enough to arrange a special little boat and a survival suit for a trip through the dark but fascinating polar night. This is only possible because tonight we are still relatively close, with the ship collecting samples in Kongsfjorden, on the north-west side of Spitsbergen. This is an open fjord with a relatively free connection to adjacent shelf. It’s 20 km long, between 4 and 10 metres wide and a maximum depth of 400 metres. This means it is largely influenced by both Atlantic water and Arctic water. It also gets a discharge of fresh water and sediments from adjacent glaciers, which we will be looking at more closely in the next few days. It has been an action-packed day today, watching polar marine night researchers in action. Night research during the day sounds odd, but I can assure you it is certainly dark enough –at any time of day.

Muddy secrets Sergei Korsun from St. Petersburg university and PhD student Olga Knyazeva were out on deck preparing a box corer, a big box-shaped instrument to go down to the seabed and bring up samples of sediment. The teamwork between scientists and crew seems to work brilliantly. The crew operate the lifting and lowering equipment and all sorts of other gear. The scientists collect their samples from it and take them in to the ship’s lab.

“Just a load of mud”, quips Sergei, and there is certainly plenty of it sploshing about in the course of the operation. No wonder there are no outdoor shoes allowed inside.

Olga drains off the water so that only the sediment is left. These two are interested in foraminifera or forams, one-celled organisms. Ice Blog readers may remember I discussed them here some time ago, in connection with research on ocean acidification. German scientists actually wrote a children’s story with Tessi and Tipo, two of these tiny ocean creatures, as the main characters. The focus there was on how increasingly acid seas are dissolving the protective shells of many organisms, especially in cold, Arctic water, where the process is faster. Every creature counts! So why should we be interested in these forams in particular? No question about it, says Olga. There are so many of them, they account for a huge proportion of biomass and we know far too little about what they are up to in the winter. Given their important role in the ecosystem, what they do in winter is something we really ought to know. The season of winter is just too long to be ignored any longer, says Olga. And ultimately, even the tiniest creatures play a role in the global foodweb. Sergei mentions another reason why climatologists and those interested in the history of the planet are so interested in these tiny creatures. They fossilize, so that scientists can use samples from the seafloor to get a record of earth’s history that goes back a very long way.

Inner clocks without daylight? Shortly afterwards, I joined Sören and Lukas from Germany’s Alfred-Wegener Institute for one of their four-hourly net-dropping exercises. For this, a big hatch is opened on the laboratory deck. This brought added excitement as there were a lot of beautifully shaped chunks of ice just floating past. Iceblogger’s delight!

We could also see the hills in silhouette in the background. Clearly there are indeed many shades of “dark”. Seagulls are following us constantly. No doubt they know fish and shrimps are being caught and are always on the lookout for an easy, tasty morsel. In this climate, I don’t blame them. And it is kind of reassuring to have their company, bright in the ship’s lights against the dark sky and sea. The wind felt icy, but the experts up here tell us it is actually relatively mild. Anyway, our two scientists dropped a longish thin net attached to a sort of circular hoop out the hatch, sampling the water.

When it came in, they take samples of small jellyfish, copepods and krill, for a fascinating project to find out about the “biological clock gene”. How can some marine organisms migrate vertically in a 24-25 hour cycle, without light to trigger this? More about that when I’ve interviewed the experts over the next couple of days.

The advantages of winter If you have been waiting for the answer to the question about reproduction in the last blog, I won’t keep you in suspense any longer. Given that the reason is unlikely to be an ideal food supply for the “babies”, some of the scientists on board think the reason could be that there fewer predators about to eat the young, if they arrive in winter. Does that seem plausible? The next post may be a day or two in arriving, as the ship will be out of range from tomorrow onwards. But I promise plenty more to come as soon as we are back in internet range. (How on earth did we live without it?!)

Food and sex in Svalbard’s icy waters?

This is my first post from the Polar Marine Night expedition, from the Kongsfjord in Svalbard.

On the flight from Oslo to Longyearbyen, the main settlement on the island, after a period with a beautiful sunset red strip in the sky, it was dark by half past midday and I realized I had seen my last sunrays for this week.

Flying in to Longyearbyen airport, I could see a white mountain, its dark silhouette outlined by the airport lights. Having been here before in the summer sun, I realized somewhere up there was the famous seed vault where safe supplies of seeds for the world’s food crops are stored under the permafrost, supposedly safe from wars or some other disastrous calamities which might require a “new start” for humanity. I was fortunate enough to visit it on a previous trip a couple of years ago. At the moment, though, the darkness reveals very little of the fascinating landscape.

New winter visitors to Ny Alesund

Our small, robust propeller plane carrying scientists and service staff from the research station, one fellow journalist as well as two young German scientists joining the scientific cruise had us in Ny Alesund late afternoon. It was strange to see the station completely in the dark, although it is not as deserted as it once was in winter, thanks to this Polar Night research. As our driver told us on the way to the harbour, (nothing is far from anywhere else in the small settlement, but hauling luggage across slippery snow and ice in the dark is something I can do without) there are around 60 people on the base, whereas once there was only a skeleton crew of around 13 over the winter.

The French-German station, the Norwegian station and the Chinese building are manned throughout the winter. The others are summer-only stations. Different scientists from around the globe come in and out for the boat trips to investigate marine life in the polar night. This is only the second year of this heightened interest in life in the dark season up here.

Select company of hardy researchers

The RV Helmer Hanssen – named after Amundsen’s navigator to the South Pole – was waiting at the quay. Built as an ice-going fishing vessel, these days the only trawling done here is in the interests of science. Since we left this evening, nets have been deployed at different levels at regular intervals bringing samples of Arctic sea life on board and into the labs. There are 16 students and professors on board, with a crew of 12 to operate the ship, round the clock. It’s an expensive business, says Stig, so they have to make maximum use of the ship time by working to a busy schedule, sleeping in shifts in between. Well, at least we have enough bunks, so we don’t have to economise by sharing those.

Nocturnal goings-on

If I hadn’t done my homework, there were times during the evening briefing by Stig and his colleague Paul Renault, when I might have been tempted to call for an interpreter , with talk of pelagic trawls, the hyper-benthos, grabs, diel vertical migration, epibenthic sleds and more of that ilk. Then comes the high-tech LOPC – a laser optical plankton counter, of course! In case you are not a marine biologist yourself, this is all about getting samples from different layers of water and the seabed to find out about the relatively unknown winter lifestyles and behavior of organisms living in the Arctic ocean. (There was some discussion about supplies of ethanol and formaldehyde, which you must not run out of if you want to take some samples home as a souvenir). It seems amazing, but there is still very little known about marine life in the polar night, because the region was so remote and inaccessible, and because people assumed where there was no light, there would be no biological activity. Now our scientists have discovered (last year was a real “eye-opener”, says Stig) that there is all sorts of activity going on.

It does not surprise me personally that a lot of creatures have to feed all the year round. But what exactly do cod, for example eat? That’s what Marine Cusa wants to find out for her PhD. I met her in the lab, where she was dissecting fish. I had a look inside the stomach of a large specimen of Atlantic cod in the lab.

Not for the faint-hearted, so I won’t go into details. There are even creatures up here who choose to reproduce in this dark season. Now presumably it’s not like with human beings, where there tends to be a rise in the birth-rate after major power cuts in some places. So why would sea creatures choose to have their young in the cold, dark, polar winter? Some of the experts here have some theories – but I’m going to save that for another day.

Feedback