Polar Ice at UN Bonn Climate Talks

… And the ice continues to melt. (Pic: I. Quaile)

The delegates to the UN climate meeting currently taking place here in Bonn are receiving an urgent appeal from polar scientists to cut emissions to slow polar ice melt and give low-lying coastal regions more time to adapt to rising sea levels.

I was very interested to hear about a side-event being held here this evening, at which the authors of this year’s key studies on developments in the Antarctic will be explaining the connections between melting polar ice and climate change impacts like rising seas, affecting regions as diverse as small island states, Bangladesh or Florida in the USA.

I interviewed Anders Levermann from PIK, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts Research and Pam Pearson, Director of ICCI, the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, both in Bonn for the event.

The ICCI decided to bring the cryosphere into the Bonn talks to sensitize delegates to the dramatic developments in the Antarctic in particular, says Pearson. Ice Blog readers (and I was so delighted to hear Pam herself is one!) will remember posts earlier this year on melting in the East and West Antarctic. I also covered these in articles for DW. The shocking thing is that the Antarctic, even East Antarctica, which was until relatively recently considered so cold it had to be safe from global warming, is already being affected by climate change. The papers on the West Antarctic even described the melt trend as “irreversible”.

“We have entered an era of irreversible climate change”.

Today, Anders Levermann, author of the East Antarctic paper and one of the world’s leading Antarctic researchers, told me “we have entered a new era of climate change, witnessed the tipping of the West Antarctic ice sheet, and this is irreversible”.

That should really shock people into action, you would think. But climate negotiations are moving, as one of the experts said to me at the meeting “at a glacial pace”. As we can see in Antarctica, though, and Greenland and other regions, those glaciers are speeding up. Maybe there is hope for the climate talks yet!

The announcements by the USA and China on possible emissions cuts have brought a new “buzz” to the Bonn conference. The fact that the key emitters could finally be getting the message and preparing to move, with the impacts of climate change hitting their own countries, has to be a positive signal. Pearson confirmed to me that people in the sunshine state of Florida, where she lives, had become more aware of the importance of melting ice caps with increasing floods and storms.

As Levermann says, Antarctica and Greenland have a huge potential to raise sea level further than previously anticipated. He was lead author on the IPCC report chapter on sea level rise. The latest IPCC report factored in some of the likely impacts from melting ice in these regions for the first time. Of course the latest research was not yet included. For the 21st century forecast, this will not make a lot of difference, says Levermann. But the fact that this irreversible Antarctic melt is now underway will make a big difference to coming generations.

There are those who dispute whether the warming of the ocean, which is causing the Antarctic melt (unlike the surface melt on Greenland) is man-made. Levermann does not rule out natural variation as a possible influence. But ultimately, he says, that is irrelevant. Greenhouse gas emissions and so human interference are warming the planet, and any further warming, whatever the cause, will speed up ice melt. So cutting emissions is the way to slow it down and, Pearson adds, gives people time to adapt to rising seas.

The combination of models based on the principles of physics, using a higher resolution than ever before, and evidence from ice cores showing what happened in the past, make for a high degree of certainty about these ice developments, says Levermann.

“The level of warming will determine the rate with which we discharge West Antarctica, and we can still prevent the tipping of East Antarctica”, the cryosphere experts told us here in Bonn.

That is a huge responsibility. Here’s hoping the message will make it into the hearts and minds of those negotiating the future of the earth’s climate and the governments they represent.

Cryosphere in Crisis?

You can’t say the latest research results on the thinning of the West Antarctic ice sheet didn’t make the media. From the news agencies through the quality media and even publications not known for their detailed science or environment coverage – nearly all reported that two separate studies each independently come to the conclusion that parts of the West Antarctic ice sheet are already “collapsing”. They say this could result in a considerable sea level rise within the next century or two. This would have devastating consequences for low-lying coastal areas around the globe.

No-one can really say they didn’t know about this. For once, the Antarctic ice has made into the headlines of the mainstream media. This is the region people tend to think of as having “eternal ice”, where global warming will “not make much difference”. There are those who criticize the media for sensationalism or exaggeration by taking over the term “collapse” for a process which will still take hundreds to thousands of years. See for example Andrew Revkin’s post on Dot Earth (New York Times), (and an excellent response by Tom Yulsman in ImaGeo: (Discover Magazine). But, semantic discussions apart – as Yulsman puts it:

“On a human timescale, 200 years or more for the start of rapid disintegration is a very long time indeed. But on a geologic timescale, it is the blink of an eye. And that’s important to keep in mind too — that in a blazing flash, geologically speaking, we humans are managing to remake the life support systems of our entire planet. This is why I think today’s news may eventually be seen as having historic significance”. At any rate, he concludes “it is yet another clear sign that human-caused changes to the planet once regarded as theoretical are now very real”.

Indeed Tom. The question is: what are we going to do about it? Has it set the alarm bells ringing? Did anybody see a rash of reactions promising quick action on reducing emissions to mitigate climate change? If so, please point me in the right direction. So far, I haven’t seen any indication of anything other than business as usual.

The West Antarctic ice sheet contains so much ice that it would raise global sea level by three to four meters if it melted completely. As it sits on bedrock that is below sea level, it is considered particularly vulnerable to warming sea water. Until now, scientists assumed it would take thousands of years for the ice sheet to collapse completely. The two new studies indicate that could happen much faster – as early as 200 years from now or, at the most, 900. Both research teams, using different methods and looking at different parts of the ice sheet, conclude that the trend is probably unstoppable.

The NASA study published in “Geophysical Research Letters” uses data from satellites, planes, ships and measurements from the shelf ice to examine six large glaciers in the Amundsen Sea over the last 20 years. The second report, from the University of Washington published in the journal “Science,” uses computer models to study the Thwaites glacier. It is considered of particular importance because it acts as a type of “lynch pin”, holding back the rest of the ice sheet.

According to NASA researcher Eric Rignot, the glaciers in the Amundsen Sea sector of West Antarctica have “passed the point of no return.” He told journalists this would mean a sea level rise of at least 1.2 meters (3.93 feet) within the next 200 years.The University of Washington scientists worked out, using topographical maps, computer simulations and airborne radar, that the Thwaites glacier is also in an early stage of collapse. They expect it to disappear within several hundred years. That would raise sea levels by around 60 centimeters (23.62 inches). The NASA study showed that sea level rises of 1.2 meters are possible

The good news, according to author Ian Joughlin, is that while the word “collapse” implies a sudden change, the fastest scenario is 200 years, and the longest more than 1,000 years. The bad news, he adds, is that such a collapse may be inevitable: “Previously, when we saw thinning we didn’t necessarily know whether the glacier could slow down later, spontaneously or through some feedback,” Joughlin says. “In our model simulations it looks like all the feedbacks tend to point toward it actually accelerating over time. There’s no real stabilizing mechanism we can see.”

The latest IPCC report does not adequately factor ice loss from the West Antarctic ice sheet into its projections for global sea level rise, on account of a lack of data. These “will almost certainly be revised upwards,” according to Sridar Anandakrishnan from Pennsylvania State University at the presentation of the University of Washington study. The scientist was not involved in the research.

NASA glaciologist Rignot said he was taken aback by the speed of the changes. “We feel this is at the point where … the system is in a sort of chain reaction that is unstoppable,” he said.

Rignot also makes the key point that this development tells us not only about the area down at the South Pole, but about the whole climate system: “This system, whether Greenland or Antarctica, is changing on a faster time scale than we anticipated. We are discovering that every day.”

My last two blog posts have been about melting of the Greenland ice sheet and melting even in the East Antarctic, which is usually cited as the last bastion against ice-destroying climate change. We are subjecting our cryosphere to huge pressures and have set a “snowball” rolling, which is picking up momentum and will ultimately carry masses of ice into a rising ocean.

Rignot says even drastic measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions could not prevent the collapse of the West Antarctic ice sheet. That is a terribly depressing thought. I would like to think this will prove wrong. But if there is any chance to avert that disaster and preserve our polar ice for thousands of years rather than just a few hundred, surely the time for action is now?

Will Antarctic share Arctic’s fate?

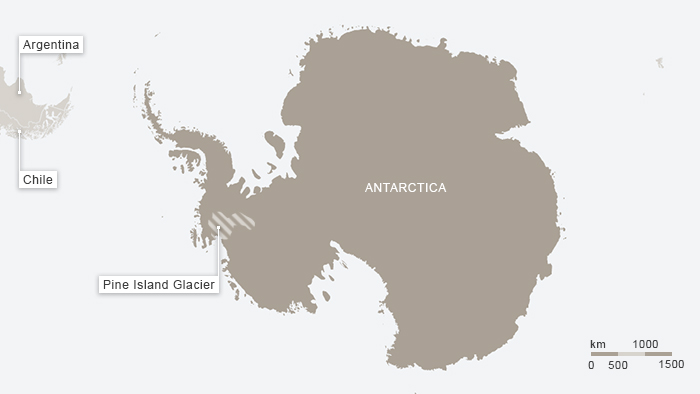

While the Arctic is melting twice as fast as the rest of the planet, and protests continue against the race for oil at huge risk to the sensitive environment, the icy regions around the south pole were long considered immune to climate change. But melting glaciers on the Antarctic Peninsula in recent years sparked doubts in the scientific community about just how stable the western region of Antarctica really is. Earlier this year, I wrote an article on the irreversible melt of the Pine Island glacier on western Antarctica. The huge iceberg that broke off last November has been in the news again, heading for the open sea.

Only the huge icy vastness of Eastern Antarctica still appeared to be safe from the perils of a warming climate. Now experts from Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) have published findings indicating that this too might no longer be the case. In a study published in “Nature Climate Change“, they write that the melting of just a small volume of ice on the East Antarctic coast could ultimately trigger a discharge of ice into the ocean which would result in unstoppable sea-level rise. They are talking about tomorrow or the next decade. Still, the prospect of more irreversible thawing in the Antarctic is a very worrying one.

“Previously, only the West Antarctic was thought to be unstable. Now we know that the eastern region, which is ten times bigger, could also be at risk”, says Anders Levermann, co-author of the study. The findings are based on computer simulations which make use of new, improved data from the ground beneath the ice sheet.PIK scientist Levermann was one of the lead authors of the sea-level section in the latest IPCC report.

“The Wilkes Basin in East Antarctic is like a bottle that is tilted”, says Matthias Mengel, lead author of the new study.”If you take out the cork, the contents will spill out”. At the moment, the “cork” is formed by a rim of ice at the coast. If that were to melt, the huge quantities of ice it holds back could shift and flow into the ocean, raising sea levels by three to four meters. Although air temperatures over Antarctica are still very low, warmer ocean currents could cause the ice along the coast to melt.

So far, there are no signs of warmer water of this sort heading for the Wilkes Basin. Some simulations suggest though that the conditions necessary for the “cork” to melt could arise within the next 200 years. Even then, the scientists say it would take around 2000 years for sea level to rise by one meter.

According to the simulations, it would take 5,000 to 10,000 years for all the ice in the affected region to melt completely. “But once this has started, the discharge will continue non-stop until the whole basin is empty”, says Mengel. “This is the basic problem here. By continuing to emit more and more greenhouse gases, we could well be triggering reactions today that we will not be able to stop in the future. ” Indeed.

The IPCC report predicts a global sea-level rise of up to 16 centimeters this century. As this could already have devastating impacts on many coastal areas around the globe, any additional factor is of key importance to the calculations. “We have presumably overestimated the stability of East Antarctica”, says Levermann. Even the slightest further increase in sea level could aggravate flooding risks for coastal cities like New York, Tokyo or Mumbai.

At the moment, the largest contribution to Antarctic ice loss and rising sea levels comes from the Pine-Island glacier in West Antarctica. As I mentioned at the start, a huge iceberg, which broke off from the glacier last year, is currently floating into the open waters of the Southern Ocean. French glaciologist Gael Durand from Grenoble University told me in an interview the huge glacier had already reached a point where its continued melting is irreversible, regardless of air temperature or ocean conditions.

Polar ice tipping points

As I get ready to head up to Tromso for the Arctic Frontiers conference and prepare my accreditation for the next routine round of climate talks here in Bonn in March, I find myself with plenty of food for thought.

It seems like not that long ago that scientists were telling us that although the Arctic is clearly melting fast, there was no need to worry about the Antarctic ice melting. But for the past 15 years or so, scientists have been observing that glaciers in West Antarctica are out of balance. Ice shelves have been breaking off and the calving fronts of glaciers have been retreating, draining huge amounts of ice into the ocean. This week I was interested and concerned to read about the results of a modelling effort, using 3 different types of model, indicating a key Antarctic glacier was melting irreversibly.

(Map courtesy of Deutsche Welle)

The Pine Island Glacier in the Antarctic hit the headlines last year when a giant iceberg broke off it. It is a key glacier because it is actually responsible for some 20 percent of the total ice loss from the region. Now scientists have found the glacier is melting irreversibly – with dramatic consequences for global sea levels. For an article for DW entitled Antarctic’s glacier retreat unstoppable, I interviewed Gael Durand of the French University of Grenoble, one of a team of scientists who have just published the new study: “We show that the Pine Island Glacier will continue to retreat and that this retreat is self-sustaining. That means it is no longer dictated by changes in the ocean or the atmosphere, but is an internal, dynamic process”, Durand told me. This will mean an increasing discharge of ice and a greater contribution to global sea level rise. “It was estimated at around 20 gigatons per year during the last decade, and that will probably increase by a factor of three or five in the coming decade. That means this glacier alone should contribute to the sea level by 3.5 to 10 millimetres a year, accumulating to up to one centimetre sea rise over the next 20 years. For one glacier, that is colossal”, says Durand.

I called up Angelika Humbert from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) to get an expert opinion on the significance of the new research. She told me 1cm over 20 years would be an “extremely high” amount. The glaciologist, who is also working on models for the Pine Island Glacier, stresses that all models include a degree of abstraction and uncertainty. However, her work also indicates that the glacier will make an increasing contribution to sea level rise in the coming years and describes the new study as a “considerable advance on the results of research to date.” Humbert says the results could well be applied to other glaciers of the same type.

Angelika Humbert from AWI took this picture flying over the Pine Island Glacier in a NASA DC8 as part of the IceBridge campaign in 2011

Durand’s new study shows that the glacier is now flowing at a rate and in a way that makes the process irreversible. Even if the air and ocean temperatures cooled off to what they were a hundred years ago – which is in no way likely – Durand is convinced the glacier would not recover. Durand says the study should arouse concern because the glacier has passed a “tipping point”, a much discussed concept in climate science. “That means because of our behaviour, our climate is changing and will continue to change a lot. I think it is one of the first times we are passing these tipping points.”

The scientist compares the situation to that of a cyclist coming down from the top of a mountain and unable to brake: “We have to fear that the retreat will continue, that other glaciers in the region will start to do the same, and that we will have a collapse of this part of the ice shelf. That would take centuries, but it would mean a rise of several metres in sea level.”

The last report by the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change (IPCC) warned of the implications if the glaciers of West Antarctica were to become unstable. “Here,” says Durand, “we have proof that that is already happening with this one.”

At the Arctic Frontiers conference two years back, I heard a lot of interesting discussions about climate tipping points. Professor Carlos Duarte Directorof the Oceans Institute at The University of Western Australia and Research Professor with the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) talked to me at length about tipping points. Let me quote him briefly:

“Tipping Points – or thresholds – are levels of pressures beyond which small response of a property of interest becomes abrupt. Once a system or ecosystem or earth system crosses beyond a threshold, the changes, e.g. in the extent of ice or rate of warming, accelerate greatly, and once the threshold is crossed, it is sometimes very difficult to return to the original state even if pressure is released or reduced.”

We discussed the possible tipping points and warning signs outlined in a key piece of research by Timothy Lenton and others. Some would argue that tipping points have already been crossed in the Arctic region, which is known to be warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the earth. One of Lenton’s other key factors is the West Antarctic ice sheet becoming unstable. Now the “eternal ice” down south could be reaching a kind of “tipping point” in places. Yes, I know this only applies to a particular region of the West Antarctic, but the implications of irreversible glacier melt there are already huge. Greenland and that West Anarctic ice sheet play a key role in storing masses of fresh water, which would have huge implications if they melted. With marine glaciers, like the Pine Island Glaciers, the melt of white ice to expose more dark ocean surface underneath would further increase warming by absorbing solar heat instead of reflecting it back.

With the EU in the news today for considering moving away from binding climate targets, and little progress in sight towards an effective new climate agreement scheduled to be agreed in Paris in 2015, this all puts me in a pensive mood, as I get ready to head north and focus on the implications of the changing climate for “Humans in the Arctic”.

“Penguins” ask Berlin to save Antarctic

Today, it seems, is World Penguin Day. If you happened to be in the German capital, Berlin, this would have been drawn to your attention by largish “penguins” visiting the embassies of Russia, China and Norway, as well as the German Agriculture Ministry, which, it may surprise you to know, is responsible for the protection of the Antarctic on behalf of the German government

Activists from “The Antarctic Ocean Alliance“, (AOA) made use of the occasion to draw attention to the need to protect the pristine ice region at the south of the world. The background is that Germany will be host to a meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCALMR) in July this year. The meeting, in Bremerhaven, home of Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for polar and marine research, will be discussing the possible creation of two Marine Protected areas (MPAs) in the Antarctic. The alliance, made up of WWF, Greenpeace, Deepwave, Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) and others, is calling on Germany to play a leading role and on other key countries to support a decision in favour of the protected areas.

Steve Campbell, Campaign Director of the AOA, stressed Germany’s long tradition of scientific polar research and the key role the country could play in Antarctic protection. The alliance stresses that the Southern ocean is under increasing pressure from climate change and resource depletion. The areas the AOA want protected now are described by the campaigners as one of the world’s last wildernesses and an essential “living laboratory” for the planet.

Feedback