From Alaska to Ottawa

Ottawa has been the setting for “Arctic Change”, another major Arctic conference this week. It is organised by the research network ArcticNet. I was not able to attend, but have been interviewing various people for an article on DW about the meeting, and about what is happening in the Arctic at the moment. One of the people I spoke to was George Divoky, who went to the meeting to put his own work into context and get the “big picture” of how climate change is having an impact on the Arctic. George is the mainstay of Friends of Cooper Island

He has a bird research station on Cooper Island, off Barrow, Alaska. For 45 years, he has been there every summer, observing a colony of black guillemots, who breed there. As he told me when I first met him during a trip to Alaska in 2008, his ornithological observation widened out into an observation of climate change over the years, witnessing some dramatic changes. I would like to share his views with you here on the Ice Blog.

Iceblogger: Why are you attending the conference and what do you expect from it?

As someone who has spent the past 45 summers studying seabirds in the Alaskan Arctic, I am very interested in hearing the findings of arctic researchers working in other disciplines and geographic areas.

I expect to be brought up to date on the most recent findings of how warming and development is affecting the ecosystems and people of the Arctic. The information I obtain allows me to put my work (which is on a single species breeding on one island) in a much larger context.

Has the Canadian chairmanship of the Arctic Council affected Canada’s interest in the Arctic?

I know little of the international politics of the Arctic but my feeling is that Canada has always had a major interest in the Arctic because of the extent of their arctic lands and the large number of villages and settlements. With all that is now going on in the Arctic, Canada’s chairmanship certainly provides an opportunity for the country to focus on the region even more.

Are there differences in attitudes to the Arctic in the various countries involved? US; Canada, Russia, Norway…?

I feel that the US (with the exception of the indigenous people who live there) tends to treat its small part of the Arctic as a place to exploit natural resources and conduct research while Canadians have a much more organic (holistic) approach to the region. My impression is that is also true for Scandinavian countries.

What has been your experience of Arctic change on Cooper Island this year?

The 2014 breeding season on Cooper Island had the lowest number of breeding pairs of Black Guillemots in the last 20 years. Breeding success in 2014 was low as all of the younger siblings in then nests died from starvation during a major windstorm that occurred in August after ice retreat and parent birds could not find sufficient prey. We also had more polar bears on the island and interactions with them than during the last few years. Polar bears were rare visitors to the island until 2002.

What impacts of the above-average rise in temperature have you seen over your years on Cooper island?

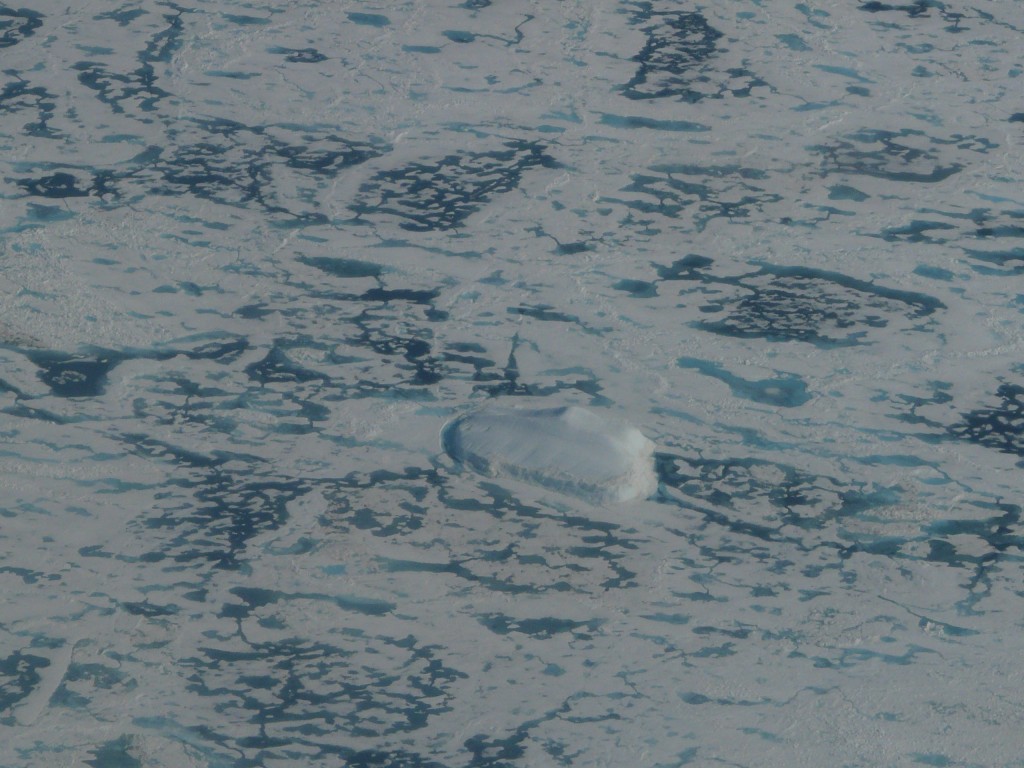

Warming first aided the guillemots (1970s and 1980) as the summer snow-free period increased and was better suited for the 90 days it takes guillemots to breed. The size of the breeding colony increased during the initial stages of warming. Continued warming (1990s to present) caused the sea ice to rapidly retreat in July and August when guillemots are feeding nestlings and the loss of ice reduced the amount and quality of prey resulting in widespread starvation of nestlings. Reduced sea ice also forced polar bears to seek refuge on the island with large numbers of nestlings being eaten by bears.

How serious is the problem of thawing permafrost?

Thawing of permafrost has the potential to drastically change terrestrial ecosystems due to changes in drainage and plant communities. The large shorebird and waterfowl populations breeding on the tundra require large areas of ponds and lakes for breeding. Melting permafrost is allowing water to drain from the surface decreasing the extent of aquatic habitats while increasing the depth for root growth which facilitates shrubs replacing tundra plants.

Do you have a sense that there is a “rush for the Arctic’s resources” or is this just media hype?

It is clear to me that there is a rapidly increasing interest in arctic resources from government and industry.

Where should the priorities of Arctic research and Arctic policy be in coming years?

While there will certainly be increased research in the Arctic in coming years I think it is important to realize that just because humans know more about a region or ecosystem it does not necessarily follow that they will be any better at protecting it from impacts – or likely to do so. Pre-development ecological research is something most governments feel they must do to satisfy concerns about environmental degradation, but the ways in which that research can limit the effects of the post-development degradation – or assist in mitigating that degradation – is unclear. Similarly, researching climate change and its effects are important but of little practical use if the research does not inform government officials and result in policies that address the causes of climate change.

With the climate conference going on in Peru – do you have the feeling the world takes the changes in the Arctic seriously?

I feel that the entire issue of current and predicted climate change is now being taken more seriously and, as a result, there is more focus on what is occurring in the Arctic since people and government now see the changes in the Arctic as being less removed from their own experience.

Are you optimistic about the future of the Arctic?

I am not optimistic that what used to be considered the “Arctic” will persist into the future. The Arctic where I do research now bears little resemblance to the Arctic I first went to in 1970. With models showing summer sea ice may soon disappear and predictions for increasing temperatures and development, it is likely that current and future generations of researchers will also be taken aback with the pace of change during their time in the region. Clearly, the Arctic as a geographic region will persist but the characteristics that are evoked by the word “arctic” (i.e. snow and ice dominated landscapes far from human industrial development) will no longer apply to the region. And, of course, the biota adapted to the arctic ecosystems of the past will have very uncertain futures given the pace of change.

What will it look like in 20, 30, 50 years?

Much of the Arctic became technically subarctic during the last 20 years. At least for the near future, winters will always be cold in the Arctic so some seasonal snow and ice cover will be present but the annual period when snow and ice are present will decrease. The rate at which these changes will take place is unclear as an Arctic that is ice free in summer (and losing land ice in Greenland) might cause more rapid changes.

Can anything happen to save it?

I was very lucky to be able to be in the Arctic in the late 20th Century but it now seems clear that with the projected increases in atmospheric CO2 and resulting increases in temperatures and ocean acidifcation that the Arctic (as well as many of the earth’s natural areas) could be unrecognizable by the middle of the 21st Century.

Arctic icon in decline

As I plan my coverage of this year’s annual UN climate conference, this time in Peru, a news item from WWF pops up in my mail box. The organization is concerned that the number of polar bears in the Beaufort See in Alaska and in north-western Canada has dropped by around 40 percent in the last ten years. Now that is a very worrying statistic.

It is based on a study published in the journal Ecological Applications: Polar bear population dynamics in the southern Beaufort Sea during a period of sea ice decline.

In 2004, it seems 1,500 polar bears were counted. The latest count showed just 900. Declining sea ice and a lack of prey seem to be the likeliest causes. Another piece of evidence to justify the decision in 2008 to list polar bears under the US Endangered Species Act.

WWF fears the worrying trend will continue if climate change is not halted. There are only between 20,000 and 25,000 polar bears left in the world. With the average air temperature in the Arctic a good five degrees centigrade higher than it was a hundred years ago, it is hardly surprising that nature is struggling to cope. As the sea ice declines, the bears are losing their habitat. You might also remember the pictures of all those walruses on the beach a few weeks ago. They too, were affected by the decline of the sea ice where they usually rest between dives.

So what can we do to halt the decline in the polar bear population? This brings me back to the forthcoming climate conference in Peru. I am finding it difficult to arouse interest in this year’s meeting. “Paris next year is the important one”, I hear. So does climate action just get put on hold for another 12 months? Tell that to the polar bears. One single conference cannot save the world from the climate catastrophes that could lie ahead if the world does not manage to reduce its emissions drastically in the next few years. UNEP’s “Emissions Gap Report 2014”, just published yesterday, says we have to be carbon-neutral by the 2nd half of this century to keep temperature rise below two degrees centigrade. There is still a huge gap between the pledges made by countries within the UNFCCC framework and what is necessary for that. Emissions would have to peak within the next ten years, says the UNEP report, based on the latest IPCC data. Otherwise we risk severe and irreversible climate change with all the droughts, floods and other impacts that come with it.

Given the need for urgent action, I fail to understand how anyone can say “forget Peru, wait for Paris”. I would be the first to stress that these conferences alone cannot halt climate change. The switch to renewable energy is already underway. But ultimately, governments have to agree to binding targets. We have seen encouraging signs from the top emitters China and the USA. Without those international negotiations, this is unlikely to have happened. Let us take the Peru conference as an opportunity to focus world interest on the urgency of climate action. Countries have to keep doing there homework. I don’t know if we will be able to turn our energy policies around in time to save the bears. But if they are to have any chance – at the risk of sounding clichéd: the time for action is now, and any major climate event is a chance to say so.

Berlin Wall – Hope for Arctic?

The statement by veteran Arctic researcher Peter Wadhams that the Arctic could be ice-free in summer as early as 2020 sparked a lot of discussion. Recently I had the chance to talk to Professor Stefan Rahmsdorf, Professor of Physics of the Oceans and head of Earth System Analysis at Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) about Wadham’s forecast.

![]() read more

read more

Acid Arctic Ocean and Russell Brand?

Is ocean acidification a term you are familiar with? If you are a regular Ice Blog reader, I would like to think you will be. But I am prompted to ask this question because the term came up during a discussion at a weekly evening class I attend, and I was flabbergasted that none of the people there had a clue what it meant. These were all university-educated professionals. That means we in the media have our work cut out for us explaining how climate change is making the seas more acidic, and why this is something we should be worried about.

This incident has reminded me that we journalists have to avoid assuming that everyone is familiar with the terms we use in our coverage on a regular basis. Climate change is the kind of topic where you want to reach a specialist audience, but also the vast majority of the population. We all have to change our habits to reduce CO2 emissions, and we all have to vote for the politicians who have the responsibility for energy and environment policy. That means we need to talk about the problems in a way everybody understands.

I am encouraged to see the BBC website had a longer article on the threat of ocean acidification a few days ago. I don’t think it has made its way into the tabloids though, correct me if I am wrong.

I was made very aware of the issue during a trip to Arctic Spitzbergen in 2010 with a team of scientists monitoring just what happens to the life forms in the sea when it becomes more acidic because it is absorbing so much of the CO2 we emit. The polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

Greenpeace provided scientists with logistic support for the ocean acidification experiments off the coast at Ny Alesund, Spitzbergen. (Pic: Irene Quaile)

Towards the end of last year, I interviewed Professor Alex Rogers from the University of Oxford, who is also the scientific director of the International Programme on the State of the Oceans, which had just published a major study on acidification.

Listen to the interview:

He told me: “The oceans are taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we’re producing at the moment. While this is slowing the rate of earth temperature rise, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in a very profound way.”

Carbon dioxide reacts with sea water to form carbonic acid. Gradually, this makes oceans more acidic.

Threat to marine life

Sea water is already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. According to the IPSO report, it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100.

Over the last 20 years, scientists around the world have been conducting laboratory experiments to find out what that would mean for the flora and fauna of the oceans. Ulf Riebesell of the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, a lead author of the report, conducted the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of the Arctic island of Svalbard in 2010. This was the project I visited.

Giant test-tubes were lowered into the ocean to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades. The experiments showed that increasing acidification decreases the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Scientists say some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Hard times for coastal residents

All this will have severe economic and social consequences. Ultimately, acidification will affect the food chain. Tropical and sub-tropical areas with warm-water corals are going to suffer. Coral reefs are home to numerous species, serve as nurseries for fish and are a valuable tourist attraction. They also protect coastlines against waves and storms.

At the same time, the polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Riebesell told me the experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.” What a horrific prospect.

The Antarctic is already affected. IPSO’s Alex Rogers told me: “We’re seeing instances where we’re finding tiny shelled molluscs, tiny snails that swim in the surface of the oceans, with corroded shells.”

These creatures play a key role in the marine food chain, supporting everything from tiny fish to whales. “One of our primary sources of marine-derived protein is in rapid decline,” says Monty Halls, manager of the UK-based Shark and Coral Conservation Trust. He describes ocean acidification as the “most serious threat to our children’s welfare.” Monty is working to produce video and cartoon material to interest the younger generation in the need to change our behavior to protect marine life.

Two German scientists Antje Funcke and Konstantin Mewes have written and illustrated a children’s story called Tipo and Tessi to make kids aware of the need to protect the ocean. So far, it has only been published in German. The English translation is available, but so far there is a lack of funding for publication.

Vicious circle of climate change

Scientists are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate. That means the more acidic the ocean becomes, the less capacity is has to act as a buffer.

Alex Rogers sees a further problem: “Carbonate structures actually weigh down particular organic carbon. In other words, they help carbon to sink out of the surface layers of the ocean into the deep sea. Anything that interferes in that process can potentially accelerate the rate of CO2 increase in the atmosphere.”

And that would be very dangerous. “The rates of CO2 increase we are seeing at the moment are probably as high as they’ve been for the last 300 million years,” says Rogers.

The IPSO scientists draw an unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions. They say a lot of these major extinction events occurred in connection with high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today.

The BBC article I mentioned earlier also mentions new research by scientists at Exeter University, indicating that increasing acidity creates conditions for animals to take up more coastal pollution, like copper. That would mean not only creatures with calcium-based shells would be endangered.

Find a celebrity champion?

The experts stress that it is not too late to halt the acidification process, although the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. This brings me back to the topics of recent Ice Blog posts: the UN climate negotiations and the need for urgent action. And of course, to the mention in the title above of the British comedian Russell Brand. This relates to another issue I have been writing about recently: the question of celebrity involvement and whether that can help inform people about and interest them in topics like climate change and the acidification of our oceans. My commentary on this, with regard to Leonardo di Caprio at Ban Ki-moon’s September summit in New York, sparked some interesting discussions.

Just this morning I was reading about Russell Brand and how his new book calling for a revolution on all kinds of issues is attracting huge interest. I have noticed that people otherwise completely uninterested in politics and social issues are at least paying some attention because their favourite comedian is talking about them. Maybe we have to get Russell Brand on board. I’m not sure what kind of action he would advocate, but there would certainly be a lot fewer people who could say they’d never heard of ocean acidification.

Can UN and EU take the heat off Alaska?

It is with a heavy heart that I write this first blog post since my holiday, catching up with the latest climate news. A piece by Alex Kirby of Climate News Network drews my attention to the fact that temperatures in Barrow, Alaska, one of the first places to feature on the Ice Blog when it was created in 2008, have risen by an astonishing 7°C in the last 34 years (looking at the average October temperature). As Alex Kirby puts it, “an increase that, on its own, makes a mockery of international efforts to prevent global temperatures from rising more than 2°C above their pre-industrial level”. We need more climate action

![]() read more

read more

Feedback