Greenland ice holds Cold War peril

It sounds like something from a science-fiction novel or a disaster movie. A hidden city under ice, housing 200 people, complete with hospital, cinema, church and research labs – and powered by a mini nuclear reactor. In fact it is reality and lies below the ice of north-west Greenland. The building of Camp Century was started in 1959, by US army engineers.

The camp was abandoned when the glacier above turned out to be shifting much faster than expected in 1967, threatening to crush the tunneled base below. Pollutants including PCBs, tanks of raw sewage and low-level radioactive coolant from the nuclear reactor were left behind.

“When the waste was deposited there, nobody thought it would get out again”, William Colgan, an assistant professor in the Lassonde School of Engineering at York University in Canada, told AFP. Colgan is co-author of a study published in August: Melting Ice could release frozen Cold War-era waste.

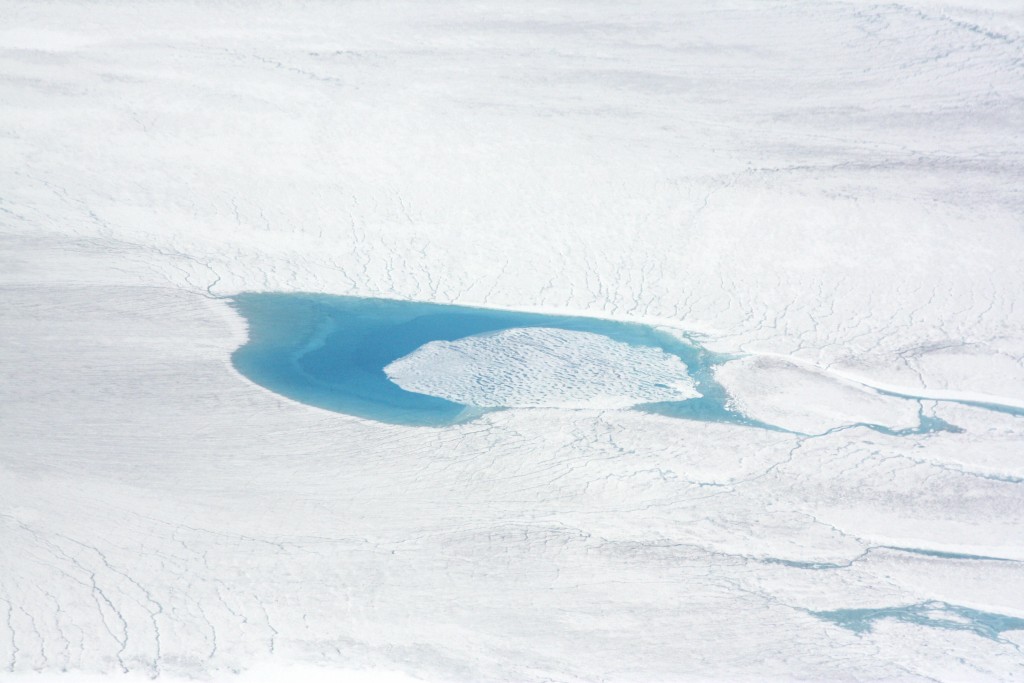

Unfortunately, recent research results have told us that the ice island of Greenland is melting even faster than previously thought. A new study published this week in the journal Science Advances using GPS to help estimate how much Greenland ice is melting, comes to the conclusion it is losing around 40 trillion pounds more ice a year than scientists previously thought. That is around 7.6 percent of a difference.

GPS maps past and future ice loss

Most measurements of ice sheet loss use a satellite that measures changes in gravity, and uses computer simulations to calculate the weight loss of ice. But co-author Michael Bevis of Ohio State University told the news agency AP that a portion of the mass calculated by the satellite as ice mass, is actually made up of rocks, which rise up to replace the ice when it goes. This distorts the picture, giving the impression there is more ice than there actually is.

The new study also reconstructs ice loss from Greenland over millennia and comes to the conclusion that it is the same parts of Greenland – the north-west and the south-east – which are losing most ice today as in the distant past. The authors say this means the rapid ice lost we have seen over the last 20 years is part of a long-term trend, being exacerbated by climate change. Damian Carrington in the Guardian, quotes Christopher Harig from the University of Arizona as an independent scientist not involved in the study:

“The new research happening now really speaks to the question: ‘How fast or how much ice can or will melt by the end of the century?’ As we understand more the complexity of the ice sheets, these estimates have tended to go up. In my mind, the time for urgency about climate change really arrived years ago, and it’s past time our policy reflected that urgency.”

Frozen hazards await release

Coming back to Camp Century – here, and elsewhere in the “frozen North”, a lot of the perils once locked safely inside an icy safe are now lurking ready to emerge when the time comes. Colgan led a study published in August in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, which found that higher temperatures could eventually result in toxic waste from the base being released into the environment. By 2090 the amount of ice melting may no longer be offset by snowfall, meaning the toxic chemicals could start leaking into the environment, the study found. Even before that, fissures in the snow could lead to melt water seeping into the crushed tunnels, currently located just 35 metres below the surface.

This is just one spectacular example of a problem that is widespread across the Arctic. Anthrax spores, nuclear waste from subs and reactors … and these are only the human-made dangers. The permafrost is sometimes described as a “time bomb”, with masses of methane and carbon stored as part of natural processes coming to the surface as the world warms.

The news story on AFP centres on who is responsible for cleaning up the pollution from the under-ice camp. The USA and Denmark signed a treaty to permit the construction of Camp Century, code-named “Project iceworm”. Officially, it was to provide a laboratory for Arctic research projects. AFP says it was also home to a “secret US effort to deploy nuclear missiles”. Maybe it was lucky the project had to be abandoned in 1967. But the legacy remains in the form of the nuclear waste left buried under the snow when the reactor was removed.

We have the technology, but…

Study author William Colgan believes the physical logistics of decontaminating the site may not be the biggest challenge involved in all of this. “The environmental hazard is relatively small and far away and there are only a few native towns close by”, AFP quotes.

I was shocked by this statement, which seems to imply that we don’t need to worry about “a few native towns”. I hope I have misunderstood him here. Surely the lives of these small communities should have top priority?

But I can follow his reasoning that establishing which country is responsible for making good the damage is harder than the actual physical clean-up. (He also mentions that the USA and Denmark have experience in similar clean-up operations around the Thule air base, which is around 240 toxic messes or worrying that all our technology cannot prevent destruction of the fragile Arctic environment if we carry out risky operations?)

A worrying precedent

Colgan says the dispute over responsibility “could help set a precedent for other conflicts arising from climate change”. Now that is a very worrying prospect. Unfortunately, it is also a highly realistic one.

When it comes to accepting responsibility for the climate change which is speeding up the melting of Greenland’s huge ice-sheet – and taking action to halt it by abandoning fossil fuels – conflicts are virtually pre-programmed.

When it comes to the costs of dealing with the migration of people forced out of their homes by sea-level rise, flooding, drought, and of ensuring progress for developing countries without climate-harming fossil fuels, states are unlikely to be queuing up to foot the bill.

Feedback