74 Search Results for: Antarctic

Polar ice set for six-metre sea level rise?

Small increases in global average temperature may eventually lead to sea level rise of six metres or more, according to evidence from past warm periods in Earth’s history.

That was the worrying message from a paper published in the journal Science this week. The researchers, part of the international “Past Global Changes” project, analysed sea levels during several warm periods in Earth’s recent history, when global average temperatures were similar to today or slightly warmer – around 1°C above pre-industrial temperatures.

I was able to talk briefly to one of the authors, Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), who was in Paris at the international scientific conference “Our common future under climate change” this week. (The article I wrote on that event, billed as the biggest climate science gathering ahead of the key COP in Paris in December, and the full interview with Rahmstorf are online now).

Rahmstorf described the new study on polar ice sheet disintegration and sea level as “a review of our state of knowledge about past changes in sea level in earth’s history, especially looking at all the data we have on past warm periods, due to the natural cycles of climate – the ice age cycles – that come from the earth’s orbit.”

He went on: ”We have had warmer times in the past, the last one was about 120,000 years ago, and we find that invariably, during these warmer times, the sea level was much higher. It was at least about six meters higher than today, even though temperatures were only a little bit higher, maybe one to three degrees warmer – depending on what period you are looking at – compared to the pre-industrial climate.”

Bad news for coastal dwellers

Not happy reading for anyone living close to the coast, if you look at temperature development today:

“Basically the message is: the kind of climate we are moving towards now – even if we limit warming to two degrees – has in the past always been associated with a sea level several metres higher, which would of course have catastrophic consequences for many coastal cities and small island nations.”

With warming currently on course to reach four degrees and more by the end of this century if greenhouse gas emissions continue on their present trajectory, this message adds yet another piece of evidence to motivate the world’s governments to come up with a new World Climate Agreement at the UN Paris summit at the end of the year – and to get moving towards a zero-carbon economy asap.

The interdisciplinary team of scientists concluded that during the last interglacial warm period between ice ages 125,000 years ago, the global average temperature was similar to the present, and this was linked to a sea-level rise of 6 to 9 metres, caused by melting ice in Greenland and Antarctica. Around 400,000 years ago, when global average temperatures were estimated to be between 1 to 2 degrees Celsius higher than –pre-industrial levels, sea level reached 6 to 13 meters higher. The lead author of the study, Andrea Dutton from the University of Florida, told journalists global average temperatures were similar to today during these recent interglacial periods, but polar temperatures were slightly higher. However, she stressed: “The poles are on course to experience similar temperatures in the coming decades”.

The Arctic is currently warming faster than the global average. IPCC estimates indicate that it could be almost two degrees warmer by 2100 compared with the temperature from 1986 to 2005 – IF the two-degree target is adhered to. Otherwise, it could rise by as much as 7.5°C.

Speed of sea level rise hard to predict

The authors of the study stress that the further back you go (they tried to estimate sea level as long as three million years ago), the more difficult it gets to calculate precisely how high sea level was, given that geological forces push and pull the Earth’s surface and can also cause vertical movement measuring tens of metres. This makes it hard to separate the geological changes in shoreline position from sea level rise caused by polar ice sheet disintegration.

Still, the authors point out that small temperature rises of between one and three degrees were, in the past, like today, linked with magnified temperature increases in the polar regions, which lasted over many thousands of years.

They conclude that even keeping to the overall two-degree warming limit is no guarantee: “Even this level sustained over a long period of time carries substantial risk of unmanageable sea level rise, not least because carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for over a thousand years”.

The researchers are not able to say how fast sea levels rose in the past, which would be a key piece of information for planning adaptation. Further research will be necessary for that.

Co-author Anders Carlson of Oregon State University says by confirming that our present climate is warming to a level associated with significant polar ice-sheet loss in the past, the study us providing “perhaps the most societally relevant information the paleo record can provide”.

Carlson heads the PALSEA2 Working Group, hosted by the Past Global Changes (PAGES) project, which used computer models and evidence from around the globe to come up with the conclusions in the study.

Stefan Rahmstorf draws a clear conclusion from the results of this research and other recent studies on instabilities in the Antarctic ice sheet and changes in ocean currents:

“This really calls for limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. And it is still feasible to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. But that requires a much stronger political will than we currently have”.

Still, the Potsdam professor is more optimistic than he used to be that advances in renewable energy and other technologies and growing awareness of the negative impacts climate change is already having around the globe could mean the UN Paris conference at the end of the year will mark a turning point.

Not that he thinks Paris can “do it all”. As you’ll see if you read my interview with him, he is hoping for the start of a process similar to the Montreal Protocol, where the original agreement was not too strong, but worked eventually by toughening up as it went along. Now that would be really good news. He told me it was time to “turn the tide of rising emissions”. Here’s hoping it happens in time to keep the sea level around the world well below that six metres that were there in the past.

Icy hotspots in focus at climate talks?

With western Europe sweltering in a record-breaking heatwave, climate scientists are meeting in Paris this week for what is regarded as the last major climate science conference before the key COP 21 in Paris at the end of this year. “Our Common Future under Climate Change” wants to be “solutions-focused”, but starts off with a resumé of the state of science as a basis.

One of the topics on the wide agenda is, of course, the cryosphere, with scientists reporting on rapid changes in the Arctic ice and permafrost, and worrying developments in the Antarctic.

As conference after conference works to prepare a new World Climate Agreement, to take effect in 2020, the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI) is concerned that the INDCSs, or Intended Nationally Determined Contributions, i.e. the climate action countries propose to take are not in line with keeping global warming to the internationally set target of a maximum two degrees centigrade. Scientists tell us this itself would already have major impacts on the world’s ice and snow.

Climate pledges way too low

Pam Pearson, the founder and director of ICCI, told journalists during a recent visit to Bonn her indication of INDCS so far was that they are ”somewhere between 3.8 and 4.2 degrees”.

Pearson and her colleagues are working hard to make the scientific evidence on climate changes in our ice and snow regions accessible and “must-reads” for the politicians and others who are preparing to negotiate the new agreement at the Paris talks at the end of the year, to replace the Kyoto protocol. She was here in Bonn at the last round of UN preparatory climate talks last month, holding a side event and briefing media and negotiators.

Pearson was part of the original Kyoto Protocol negotiating team. She is a former U.S. diplomat with 20 years’ experience of working on global issues, including climate change. She says she resigned in 2006 in protest over changes to U.S. development policies, especially related to environmental and global issues programmes. From 2007-2009, she worked from Sweden with a variety of organizations and Arctic governments to bring attention to the potential benefit of reductions in short-lived climate forcers to the Arctic climate, culminating in Arctic Council ministerial-level action in the Tromsø Declaration of 2009.

Pearson founded ICCI immediately after COP 15 to bring greater attention and policy focus to the “rapid and markedly similar changes occurring to cryosphere regions throughout the globe”, and their importance for the global climate system.

IPCC reports already out of date

At the briefing in Bonn a couple of weeks ago, she said:

“Certainly through AR5, (the 5th Assessment Report of the IPCC) the science is available to feed into the negotiations. But I think what we see as a cryosphere organization, participating as civil society in the negotiations – and I think also, very importantly, what the IPCC scientists see – is a lack of understanding of the urgency of slowing down these processes and the fact that they are irreversible. This is not like air or water pollution, where if you clean it up it will go back to the way it was before. It cannot go back to the way it was before and I think that is the most important aspect that still has not made its way into the negotiations”.

Scientists taking part in the event organized by the ICCI in Bonn stressed that a lot of major developments relating especially to Antarctica and to permafrost in the northern hemisphere was not available in time for that IPCC report. This means the scientific basis of AR5 is already way out of date, and that it does not include very recent important occurrences.

Sea ice in decline

Dirk Notz from the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg heads a research group focusing on sea ice and rapid changes in the Arctic and Antarctic.

He told journalists in Bonn: “Over the last 10 years or so we’ve roughly seen a fifty percent loss of Arctic sea ice area, so this ice is currently retreating very, very rapidly. In the Antarctic, some people are talking about the increase of sea ice. Just to put things into perspective: there is a slight increase, but it’s nothing compared to the very rapid loss that we’ve seen in the Arctic.“

The slight increase in sea ice in the Antarctic is certainly not an indicator that could disprove climate warming, as some of a skeptical persuasion would like to have us believe.

“In the Antarctic, the changes in sea ice are locally very different. We have an increase in some areas and a decrease in other areas. This increase in one area of the southern ocean is largely driven by changes in the surface pressure field. So the winds are blowing stronger off shore in the Antarctic, pushing the ice out onto the ocean, and this is why we have more sea ice now than we used to have in the past. Our understanding currently says that these changes in the wind field are currently driven by anthropogenic changes of the climate system,“ said Notz.

He stresses that as far as the Arctic is concerned, the loss of sea ice is very clearly linked to the increase in CO2. The more CO2 we have in the atmosphere, the less sea ice we have in the Arctic.

Changing the face of the planet

Notz stresses the speed with which humankind is currently changing the face of the earth:

“Currently in the Arctic, a complete landscape is disappearing. It’s a landscape that has been around for thousands of years, and it’s a landscape our generation is currently removing from the planet, possibly for a very long time. I think culturally, that’s a very big change we are seeing.”

At the same time, he says the decline in the Arctic sea ice could be seen as a very clear warning sign:

“Temperature evolution of the planet for the past 50 thousand years or so shows that for the past 10 thousand years or so, climate on the planet has been extremely stable. And the loss of sea ice in the Arctic might be an indication that we are ending this period of a very stable climate in the Arctic just now. This might be the very first, very clear sign of a very clear change in the climatic conditions, like nothing we’ve seen in the past 10,000 years since we’ve had our cultures as humans.”

Simulations indicate that Arctic summer sea ice might be gone by the middle of this century. But Notz stresses that we can still influence this:

“The future sea ice loss both in the Arctic and the Antarctic depends on future CO2 emissions. A rapid loss of Arctic summer sea ice in this decade is possible but unlikely. Only a very rapid reduction of CO2 might allow for the survival of Arctic summer sea ice beyond this century.”

Antarctic ice not eternal

Whereas until very recently, the Antarctic ice was regarded as safe from climate warming, research in the last few years has indicated that even in that area, some possibly irreversible processes are underway. This relates to land ice rather than sea ice.

Ricarda Winckelmann is a scientist with the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research (PIK). She told journalists and climate negotiators at the Bonn talks that Antarctica could be regarded as the “sea level giant”. The global sea level would rise by five metres if West Antarctica’s ice sheet melted completely, 50 metres for the East Antarctic ice sheet.

“Over the past years, a couple of regions in Antarctica have really caught our attention. There are four hotspots. They have all changed rapidly. There have been a number of dynamic changes in these regions, but they all have something in common, and that is that they bear the possibility of a dynamic instability. Some of them have actually crossed that threshold, some of them might cross it in the near future. But they all underlie the same mechanism. That is called the marine ice sheet instability. It’s based on the fact that the bottom topography has a certain shape, and it’s a purely mechanical, self-enforcing mechanism. So it’s sort of driving itself. If you have a retreat of a certain region that undergoes this mechanism, it means you cannot stop it. “

The hotspots she refers to are the Amundsen Basin in West Antarctica, comprising the Pine Island and Thwaites glaciers, which are the fastest glaciers in Antarctica:

“It has been shown in a number of studies last year that it actually has tipped. Meaning it has crossed that threshold, and is now undergoing irreversible change. So all of these glaciers will drain into the ocean and we will lose a volume that is equivalent to about a metre of global sea level. The question is how fast this is going to happen.”

Next comes the Antarctic peninsula, where very recent research has indicated that warm water is reaching the ice shelves, leading to melting and dynamic thinning.

Even in East Antarctica, which was long considered virtually immune to climate change, Winckelmann and her colleagues have found signs that this same mechanism might be at work, for instance with Totten Glacier:

“There is a very recent publication from this year, showing that (…) this could possibly undergo the same instability mechanism. Totten glacier currently has the largest thinning rate in East Antarctica. And it contains as much volume as the entire West Antarctic ice sheet put together. So it’s 3.5 metres worth of global sea level rise, if this region tips”, says the Potsdam expert.

Pulling the plug?

The other problematic area is the Wilkes Basin.

“We found that there is something called an ice plug, and if you pull it, you trigger this instability mechanism, and lose the entire drainage basin. What’s really striking is that this ice plug is comparably small, with a sea-level equivalent of less than 80 mm. But if you lose that ice plug, you will get self-sustained sea level rise over a long period of time, of three to four metres.“

This research is all so new that it was not included in the last IPCC assessment:

“We’ve known that this dynamic mechanism exists for a long time, it was first proposed in the 1970s. But the observation that something like this is actually happening right now is new,” Winckelmann stresses.

Clearly, this is key information when it comes to bringing home the urgent need for rapid climate action.

Pam Pearson stresses that these changes in themselves have a feedback effect, and have an impact on the climate:

“The cryosphere is changing a lot more quickly than other parts of the world. The main focus for Paris is that these regions are moving from showing climate change, being indicators of climate change, to beginning to drive climate change, and the risks of those dynamics beginning to overwhelm anthropogenic impacts on these particular areas is growing as the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere goes up, as the temperature rises.”

Clilmate factor permafrost

This applies in particular to the effect of thawing permafrost. Susan Natali from the US Woods Hole Research Centre is co-author of a landmark study published in Nature in April. She also joined the ICCI event in Bonn:

“Carbon has been accumulating in permafrost for tens of thousands of years. The amount of carbon currently stored in permafrost is about twice as much as in the atmosphere. So our current estimate is 1500 billion tons of carbon permanently frozen and locked away in permafrost. So you can imagine, as that permafrost thaws and even a portion of that gets released into the atmosphere, that this may lead to a significant increase in global greenhouse gas emissions.”

The study was conducted by an international permafrost network. “The goal is to put our current understanding of the processes in permafrost regions into global climate models. The current IPCC reports don’t include greenhouse gas emissions as a result of permafrost thaw”, says Natali.

Permafrost regions make up some 25% of the northern hemisphere land area. The scientists say between 30 and 70 percent of it could be lost by 2100, depending on the amount of temperature rise. There is still a lot of uncertainty over how much carbon could be released, but Winckelmann and her colleagues think thawing permafrost could release as much carbon into the atmosphere by 2100 as the USA, the world’s second biggest emitter, is currently emitting.

The time for action is now

“The thing to keep in mind is that the action we take now in terms of our fossil fuel emissions is going to have a significant impact on how much permafrost is lost and in turn how much carbon is released from permafrost. There is some uncertainty, but we know permafrost carbon losses will be substantial, they will be irreversible on a human-relevant time frame, and these emissions of ghgs from permafrost need to be accounted for if we want to meet our global emissions targets”, says Winckelmann.

The challenge is to convince politicians today to act now, in the interests of the future. Pam Pearson and her colleagues are working to have a synthesis of what scientists have found to date accessible to and understandable for the negotiators who will be at COP21 in Paris in December.

In terms of an outcome, she says first of all we need higher ambition now, in the pledges being made by different countries. The lower the temperature rise, the less the risk of further dynamic change processes being set off in the cryosphere. The other key factor is to make sure there is flexibility to up the targets on a regular basis, without being tied to a long negotiating process. The current agreement draft envisages five year reviews.

“There are a number of cryosphere scientists who actually expect these kinds of signals from cryosphere to multiply, and that there may be some dramatic developments just over the next three to five years, that may finally spur some action”, Pearson says.

Here’s hoping the UN negotiators will not wait for further catastrophic evidence before committing to an effective new climate treaty at the end of this year.

Further reading from my coverage:

Civil Society heats up climate debate

Thicker Antarctic ice – good for the climate?

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable?

Climate change risk to icy East Antarctica

Ice paradoxes from pole to pole

Returning after a longish break with little access to news and data, there are several ice and snow stories jumping out of my mailbox at me. I’ve picked out two which those of a skeptical persuasion might say disprove some key climate assumptions, but which actually, in fact, confirm some trends and predictions.

Worrying, but not unexpected, are the latest measurements of the extent of the Arctic sea ice. In February, the experts at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) based in Boulder, Colorado, noted a record for the lowest observed maximum sea ice extent. Although it seems the sea ice did grow at some points during March, the overall for the month was the lowest recorded since satellite measurements began in 1979. The average extent for the month was 14.39 million square km – some 1.13 million square km below the 1981-2010 long-term average. The previous March low of 14.45 million square km was recorded in 2006.

In the Arctic Journal, Kevin McGwin quotes Andy Mahoney, a geophycisist with the Sea Ice Group at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, as saying the irregular pattern, with a kind of “double dip”, with the ice decreasing, increasing, then decreasing again, is “a pretty unusual event, regardless of the reason”. Normally, the ice levels would increase to the seasonal maximum first in March, then decline.

One reason, Mahoney says, could be the wind blowing ice into the regions where ice growth was observed, according to the NDSIC the Bering Sea, Davis Strait and around Labrador.

No contradiction to climate warming theory

The NSDIC says warm conditions in the Bering Sea and the Russian Sea of Okhotsk contributed to the record low winter ice maximum.

The overall downward trajectory, however, is clear. The brief increase in March is not a sign that the sea ice is recovering. Mahoney told the Arctic Journal parts of Alaska had seen abnormally high temperatures this winter, which was in line with the overall seasonal ice observations.

“What drives the maximum extent is what happens at the margins, and they can grow and retreat due to short-term variants. The conditions in the central Arctic, far from the action, are indicative of the warm year we’ve had in Alaska,” he said. Barrow, on Alaska’s northern coast, far away from the southern margin, for example, saw a lot of broken ice this winter, according to Maloney.

WWF expressed concerned about the latest figures:

“This is not a record to be proud of. Low sea ice can create a series of reactions that further threaten the Arctic and the rest of the globe,” said Alexander Shestakov, Director, WWF Global Arctic Programme.

“This chilling news from the Arctic should be a wakeup call for all of us,” said Samantha Smith, the leader of WWF’s Global Climate and Energy Initiative. She stresses the need to cut global emissions to halt the Arctic melt.

The proportion of thick Arctic ice that lasts multiple years has dwindled over the past two decades. A recent study shows that Arctic sea ice has thinned by 65 per cent since 1975, leaving ice that is more susceptible to melting.

Writing for Alaska Dispatch News (AND), Yereth Rosen notes that the most dramatic changes in the Arctic sea ice extent have been in the melt season, not in the period of maximum winter coverage. He quotes NSIDC scientist Julienne Strove, who led a study published last year in Geophysical Research Letters which showed the open-water season is lengthening, mostly because of extended melt in summer and autumn. So is this additional winter record a sign of more melting to come? Only time will tell, but the signs are not looking good.

Warmer temperatures, more snow? Belgian International Polar Foundation shot of director and explorer Alain Hubert in the Antarctic.

A story from the opposite pole has also attracted attention. It says climate change is actually increasing the amount of snow in the Antarctic. Puzzling? Not necessarily.

More heat, more snow?

An international study headed by Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research (PIK) comes to the conclusion that every degree of regional warming could increase snowfall there by around five percent. The estimate is based on ice cores and climate modeling.

The information adds a new element to calculations of how much the Antarctic will contribute to global sea level rise. Some people might assume more snow would stop the Antarctic from losing mass. In fact the increasing weight of new snow and ice can make it slide towards the coast and into the ocean faster. In this connection, you might like to read some more stories on these Antarctic issues:

Thicker-ice-in-the-antarctic-good-news-for-the-climate?

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable

Anders Levermann, one of the new study authors, whom I have spoken to several times on the effects of climate change on the Antarctic and global sea levels, says the latest results back up earlier conclusions that the Antarctic will lose more ice than it will gain and thus have a major influence on global sea level. Levermann, from PIK, is also one of the lead authors of the sea-level chapter of the IPCC report. He stresses that the latest study just provides yet another piece of the “jigsaw puzzle” coming together on how global sea level is likely to develop in the future.

If the world leaders called on to come up with a new world climate agreement at the end of this year need any more motivation, this scientific research from both ends of the world should really give them an extra push.

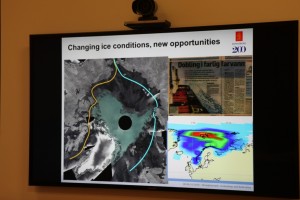

Norway’s Polar Satellite Centre

Polar orbit satellites monitor what’s happening at the ends of the planet – and, of course, the regions in between. Ice conditions, land movement, shipping, pollution – but how does that information actually make its way to the scientists and authorities who evaluate it and use it as a basis for all kinds of decisions?

During my recent visit to Arctic Norway, I had the chance to visit a facility that plays a key role in collecting and disseminating satellite data on the polar regions. On the outskirts of Tromso, Norway’s “Gateway to the Arctic”, there is a satellite ground station, run by KSat, or Kongsberg Satellite Services AS. It is a Norwegian commercial company which provides ground station and earth observation services for polar orbiting satellites. With three interconnected polar ground stations: Tromsø at 69°N, Svalbard (SvalSat) at 78°N and Antarctic TrollSat Station at 72°S, combined with a mid-latitude network of stations in South Africa, Dubai, Singapore and Mauritius, KSAT operates over 70 antennae positioned for access to polar and geostationary orbits.

The Tromso station has contact to 85 satellites every day, and every month the station monitors some 15,000 passes of these satellites overhead.

High demand for high-tech service

High demand for high-tech service

When it comes to which businesses stand to gain from climate change, the providers of satellite data have to rank high on the list. There is a huge demand for data from space, and KSat, it seems, is the biggest company worldwide carrying out this kind of activity.

While I was in town for the Arctic Frontiers conference, two colleagues and I were shown the facility on a beautiful wintry Saturday morning by Jan Petter Pedersen, the Vice President of the company, who is responsible for developing products to expand the business. He studied physics in Tromso and got into satellites during that time, he told us, going on to a PHD in remote sensing. Pedersen has been at KSat for 20 years and says the technology has come a long way in that time. These days, it’s all about remote control via pcs.

We tend to take satellite data for granted. But if you think about it, somebody has to pick up the masses of data from all those satellites circling over the poles and pass the appropriate images to those who need them. Energy, environment, security – these are key areas which make use of the data. In the Tromso station, that data is provided to those who need it more or less in real-time. The company says it can get the data down and sent on to its destination anywhere in the world within 20 minutes. So if you want to detect an oil spill in – say – the Gulf of Mexico? – The chances are, you will get information from this Arctic town.

Some companies own and operate their own satellites, and distribute the data. KSat doesn’t own any satellites, but has agreements to use data. They can access radio data from almost all satellites in operation today.

The USA and Canada are the biggest market for the company’s services, says Pedersen. Then comes Europe, followed by Asia.

The world’s largest polar ground station is the one on the Arctic island of Svalbard. I wasn’t able to visit it during my winter trip – put it must be pretty impressive, with more than 30 antennae.

Satellite monitoring as deterrent to polluters?

When it comes to oil spill detection or monitoring, satellite images play a key role.

Optical sensors have limitations in bad weather, so radar satellite data are of key importance, Pedersen explains. Oil spill detection is the most important of KSat’s earth observation activities. EMSO (European marine Safety Agency) in Lisbon is responsible for European oil spill detection. They get satellite data from 4 providers of satellite data, of which KSat is the biggest. It covers 60% of the waters from the Barents Sea to the Bay of Biscay and the Baltic.

In 2008 there were 10.77 possible reported spills per million km2. In 2011, this was down to 5.08, Pedersen told us. I asked why they talk of “possible”. It seems it is not always possible to be 100 percent sure what the satellite detects is an oil spill. The reliability is somewhere over 60 percent. Pedersen believes the satellite service plays a role in decreasing the figure. As it becomes increasingly well known that satellites are observing and collecting the data, there is a higher awareness that oil spills are being detected. Presumably this is a deterrent to deliberate discharges of oil as well as a key source of information on accidents.

From pirates to icebergs

Another key use for satellite data is in monitoring ship traffic, including detecting, tracking and identifying vessels. This means the authorities can spot illegal activities and inform the coast guards. This helps in finding pirates, for instance.

Tracking icebergs and monitoring ice development have also been aided by the growing availability of satellite data. The NSIDC is one of KSat’s most important customers. They need the data to map the extent and condition of the ice.

Satellite data shows ice changes.

Ships frozen into the ice for research purposes such as the Lance, use satellite images via Tromso. Many other ships use them to chart a course when operating in ice.

Monitoring fishing activities, offshore oil exploration, tracking land movement – all these activities rely on satellite information today.

Pedersen told us the Norwegian capital Oslo is sinking at a rate of 2 cm a year. He also mentioned a landslide risk area outside of Tromso, where a mountain is sliding into the ocean. Ultimately, it will go into the fjord and create a tsunami effect, says Pedersen. That would endanger the settlement. It is moving at 15mm per year. The satellites are keeping an electronic eye on it.

Norway, incidentally, is the country with the highest use of data per person. Most of it is maritime. So it seems fitting that the country should be the location of some of the world’s most important ground stations. There is more to the picturesque Arctic harbour town of Tromso than meets the eye – I can tell you that even without satellite data!

Climate action from Peru to Paris

Today is the first of December. It’s the start of the meteorological winter in the northern hemisphere, towards the end of what looks set to be the warmest year since records began. It is also the day when the annual UN climate conference gets underway in Lima, Peru. Negotiators from around the world will try to hammer out the details of a new World Climate Agreement to halt global warming by reducing CO2 emissions. For our polar ice, that agreement can’t come fast enough.

After five years of frustration following the failure of the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009, 2014 may well go down in history as the year when climate change made a comeback onto the international agenda. Although there is still one year to go until the key Paris meeting which is scheduled to come up with a new World Climate Agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol, 2014 has seen several milestones on the path to a low-carbon future.

In September, the UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon gave the issue top priority, by holding his own special climate summit in New York. It was accompanied by marches in the USA and other parts of the world, organized by a growing grassroots movement to combat climate change. Meanwhile, the world’s biggest emitters, China and the USA, finally signaled their intention to commit to action on climate change.

No time for delay

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, has left no doubt about the need for urgent action, says Professor Stefan Rahmstorf from Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:

“We see that global temperatures have risen by almost one degree centigrade in the last 100 years, we see that global sea level has risen by nearly 20 centimeters in the last 100 years. We see that the mountain glaciers and the Arctic ice cover is in retreat, the continental ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are shrinking, losing mass, contributing to sea level rise, we see extreme events on the rise. For example the number of record-breaking hot months has increased five fold as compared to what you get by chance in a stationary climate.”

The international community has agreed, based on the scientific evidence available, that a temperature rise of two degrees is the maximum possible without exposing the world to potentially devastating climate change. That means limiting the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet. But with those emissions still on the rise, that goal is nowhere in sight, says Rahmstorf, and climate change is already having an impact after just under one degree of warming:

“If we don’t stop this process, we will go well beyond two degrees centigrade, and we will leave the range we are familiar with throughout human history. We will be way outside that into uncharted and I think very dangerous waters.”

Peru prepares the way for Paris

Experts see the world on track for a temperature rise of at least four degrees, unless emissions are reduced substantially in the very near future. The latest figures indicate that to stay within the two degree limit, emissions would have to peak within the next ten years and the world become virtually carbon-neutral in the second half of this century.

Peru’s Environment Minister and COP 20 President Manuel Pulgar-Vidal told me in Bonn this summer he was optimistic about the Lima meeting. (Pic: Quaile)

That is why Peru, like every climate conference, is important, says UN climate chief Christiana Figueres. She stresses that climate protection is an ongoing process. Countries have until March 2015 to put their planned contributions on the table. The EU made a start by announcing its targets last month. The USA and China went on to give encouraging signals:

“The fact is that most countries around the world are currently doing their homework and figuring out on a national scale what is financially, politically, economically, technically possible for them to contribute towards the solution,” says Figueres.

But while that homework continues in the countries of the world, the negotiators assembling in Lima will have to make progress on drafting the universal climate agreement, which is scheduled to be agreed in Paris in December 2015 and to come into effect in 2020.

A price on CO2

Ottmar Edenhofer is the chief economist at the Potsdam Climate Institute. He is also co-chair of the IPCC group concerned with ways of tackling climate change. He says the world has only around 20 to 30 years left to solve the emissions problem. He stresses it is not a question of technology. Alternative energy technologies are there to solve the problem. Yet fossil fuels have been enjoying a renaissance, says the climate expert. The key, he says, is to put a price on carbon, making it too expensive to pump CO2 into the atmosphere. The world only have a limited carbon budget. That means we can only put another one thousand gigatonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere to keep temperature rise below the two-degree threshold and avoid the risk of what Edenhofer describes as “very severe climate change impacts”.

“Space to store CO2 in the atmosphere is becoming scarce”, Edenhofer explained to me recently during a visit to Potsdam. “And when things are scarce, you have to put a price on them. That is the only way to show investors, consumers and companies where they should be investing their money.” The window of opportunity is closing, says Edenhofer. If we keep on with business as usual, we will have used up all our carbon budget in two to three decades.

UN climate chief Figueres agrees that putting a price on pollution by CO2 is a very important component of the shift towards a low carbon economy.

“What we have done over the past 150 years is assumed there is no cost to the irresponsible use of the environment, and we have proceeded as though the environment were constantly renewable, where it is not”, Figueres told me in an interview conducted in her office here in Bonn, right next to our Deutsche Welle building. Putting a price tag on CO2 emissions would mean they could be costed in economic decision-making.

Haggling out the details

The negotiators in Lima have their work cut out for them. Countries with large fossil fuel reserves are reluctant to agree to emissions reductions which would destroy their source of revenue. But Edenhofer is optimistic that ultimately all countries will realize that climate change will pay off in the end.

„We have to assume that people will see sense. They will realize that the long-term consequences of business as usual will be irreversible climate change, with all the problems that brings with it”.

The economist says protecting the climate would also bring the kind of short-term benefits politicians are looking for. He cites the change in China’s policies as an example:

“The drastic air pollution in Beijing is already making it less attractive as a business location. And the reason the Chinese government is thinking very seriously about reducing emissions is because it would also be a step towards improving their air quality.”

Funding boost for UN talks

After years of stagnation and frustration, there are signs that progress is being made on climate change. At a key meeting in Berlin this month, countries pledged a total of almost 10 billion dollars to the Green Climate Fund, which was set up to help poorer countries adapt to climate change. This could motivate developing countries and emerging economies to sign up to a new world climate agreement. So far, many of them have been reluctant to limit their own emissions, as the wealthy industrialized states are the ones who have caused the problem by emissions in the past.

Although both the money pledged for adaptation and the emissions cuts proposals currently on the table are still insufficient and things are moving slowly, German scientist Rahmstorf compares the likelihood of a breakthrough to the fall of the Berlin Wall, 25 years ago.

“If you had asked people just a few months before that how likely it was that the wall comes down, nobody would have said it’s going to happen”, says the Potsdam expert and IPCC author. He says these kind of processes in society are hard to predict – and the signs are encouraging.

He cites the “huge success story” of renewable energies and the considerable emissions reductions by the EU countries since 1990 as encouraging signs. This did not hamper economic growth, says Rahmstorf:

“It shows that your can decouple emissions from economic growth and welfare”.

Ultimately, halting climate change is not something which can be achieved solely within the UN negotiations. This year for the first time a pre-conference meeting was held in Peru to involve non-governmental groups in the process. The transition to a climate-saving low-carbon society requires action across the board. But it is the governments of the world who have to enter into binding agreements, and that means plenty of hard work ahead for the negotiators in Peru over the next two weeks.

Listen to my Peru conference preview on Living Planet.

Feedback