74 Search Results for: Antarctic

Berlin Wall – Hope for Arctic?

The statement by veteran Arctic researcher Peter Wadhams that the Arctic could be ice-free in summer as early as 2020 sparked a lot of discussion. Recently I had the chance to talk to Professor Stefan Rahmsdorf, Professor of Physics of the Oceans and head of Earth System Analysis at Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) about Wadham’s forecast.

![]() read more

read more

Acid Arctic Ocean and Russell Brand?

Is ocean acidification a term you are familiar with? If you are a regular Ice Blog reader, I would like to think you will be. But I am prompted to ask this question because the term came up during a discussion at a weekly evening class I attend, and I was flabbergasted that none of the people there had a clue what it meant. These were all university-educated professionals. That means we in the media have our work cut out for us explaining how climate change is making the seas more acidic, and why this is something we should be worried about.

This incident has reminded me that we journalists have to avoid assuming that everyone is familiar with the terms we use in our coverage on a regular basis. Climate change is the kind of topic where you want to reach a specialist audience, but also the vast majority of the population. We all have to change our habits to reduce CO2 emissions, and we all have to vote for the politicians who have the responsibility for energy and environment policy. That means we need to talk about the problems in a way everybody understands.

I am encouraged to see the BBC website had a longer article on the threat of ocean acidification a few days ago. I don’t think it has made its way into the tabloids though, correct me if I am wrong.

I was made very aware of the issue during a trip to Arctic Spitzbergen in 2010 with a team of scientists monitoring just what happens to the life forms in the sea when it becomes more acidic because it is absorbing so much of the CO2 we emit. The polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

Greenpeace provided scientists with logistic support for the ocean acidification experiments off the coast at Ny Alesund, Spitzbergen. (Pic: Irene Quaile)

Towards the end of last year, I interviewed Professor Alex Rogers from the University of Oxford, who is also the scientific director of the International Programme on the State of the Oceans, which had just published a major study on acidification.

Listen to the interview:

He told me: “The oceans are taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we’re producing at the moment. While this is slowing the rate of earth temperature rise, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in a very profound way.”

Carbon dioxide reacts with sea water to form carbonic acid. Gradually, this makes oceans more acidic.

Threat to marine life

Sea water is already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. According to the IPSO report, it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100.

Over the last 20 years, scientists around the world have been conducting laboratory experiments to find out what that would mean for the flora and fauna of the oceans. Ulf Riebesell of the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, a lead author of the report, conducted the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of the Arctic island of Svalbard in 2010. This was the project I visited.

Giant test-tubes were lowered into the ocean to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades. The experiments showed that increasing acidification decreases the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Scientists say some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Hard times for coastal residents

All this will have severe economic and social consequences. Ultimately, acidification will affect the food chain. Tropical and sub-tropical areas with warm-water corals are going to suffer. Coral reefs are home to numerous species, serve as nurseries for fish and are a valuable tourist attraction. They also protect coastlines against waves and storms.

At the same time, the polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Riebesell told me the experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.” What a horrific prospect.

The Antarctic is already affected. IPSO’s Alex Rogers told me: “We’re seeing instances where we’re finding tiny shelled molluscs, tiny snails that swim in the surface of the oceans, with corroded shells.”

These creatures play a key role in the marine food chain, supporting everything from tiny fish to whales. “One of our primary sources of marine-derived protein is in rapid decline,” says Monty Halls, manager of the UK-based Shark and Coral Conservation Trust. He describes ocean acidification as the “most serious threat to our children’s welfare.” Monty is working to produce video and cartoon material to interest the younger generation in the need to change our behavior to protect marine life.

Two German scientists Antje Funcke and Konstantin Mewes have written and illustrated a children’s story called Tipo and Tessi to make kids aware of the need to protect the ocean. So far, it has only been published in German. The English translation is available, but so far there is a lack of funding for publication.

Vicious circle of climate change

Scientists are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate. That means the more acidic the ocean becomes, the less capacity is has to act as a buffer.

Alex Rogers sees a further problem: “Carbonate structures actually weigh down particular organic carbon. In other words, they help carbon to sink out of the surface layers of the ocean into the deep sea. Anything that interferes in that process can potentially accelerate the rate of CO2 increase in the atmosphere.”

And that would be very dangerous. “The rates of CO2 increase we are seeing at the moment are probably as high as they’ve been for the last 300 million years,” says Rogers.

The IPSO scientists draw an unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions. They say a lot of these major extinction events occurred in connection with high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today.

The BBC article I mentioned earlier also mentions new research by scientists at Exeter University, indicating that increasing acidity creates conditions for animals to take up more coastal pollution, like copper. That would mean not only creatures with calcium-based shells would be endangered.

Find a celebrity champion?

The experts stress that it is not too late to halt the acidification process, although the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. This brings me back to the topics of recent Ice Blog posts: the UN climate negotiations and the need for urgent action. And of course, to the mention in the title above of the British comedian Russell Brand. This relates to another issue I have been writing about recently: the question of celebrity involvement and whether that can help inform people about and interest them in topics like climate change and the acidification of our oceans. My commentary on this, with regard to Leonardo di Caprio at Ban Ki-moon’s September summit in New York, sparked some interesting discussions.

Just this morning I was reading about Russell Brand and how his new book calling for a revolution on all kinds of issues is attracting huge interest. I have noticed that people otherwise completely uninterested in politics and social issues are at least paying some attention because their favourite comedian is talking about them. Maybe we have to get Russell Brand on board. I’m not sure what kind of action he would advocate, but there would certainly be a lot fewer people who could say they’d never heard of ocean acidification.

Coal, climate, cryosphere

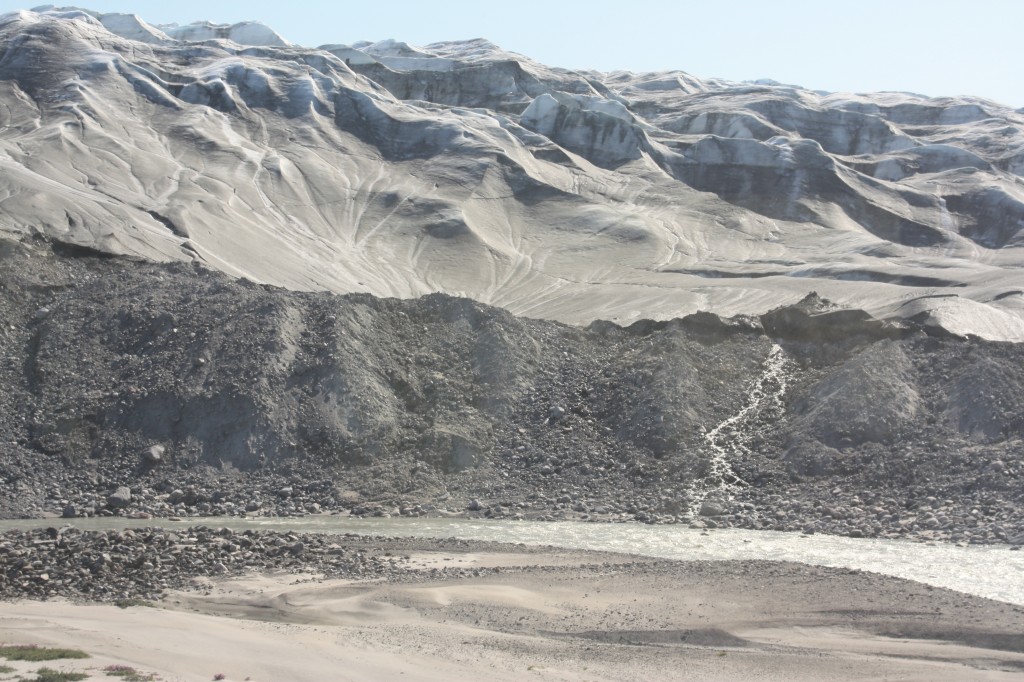

The Greenland ice sheet is melting faster. Scientists also report a decreasing albedo with snow becoming darker. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Fossil fuel power plants are still on the increase – committed carbon emissions are rising fast. At first glance you might respond to that with “so what’s new”? Well, a study is new, which indicates that in spite of all the political rhetoric in a lot of places about switching to renewable energies and moving away from fossil fuels, we are building more fossil fuel power plants than ever before. Unsurprisingly, that is leading to an increase of carbon dioxide emissions, which is bad news for plans to keep global temperature rise below 2°Celsius. It is extremely bad news for those of concerned about the cryosphere and the increasing melt rates of Greenland and parts of Antarctica. The main problem, the authors tell us, is that we have already committed to huge emissions by investing in polluting technologies.

Steven Davis of the University of California, Irvine and Robert Socolow of Princeton University in the US, report in the journal Environmental Research Letters that existing power plants will emit 300 billion tons of additional carbon dioxide into the atmosphere during their lifetimes. In this century alone, emissions from these plants have grown by 4% per year.

The two scientists have already reported on the increasing costs of delay in phasing out fossil fuel sources of energy, notes Tim Radford of the Climate News Network. Thanks again to you people for drawing attention to the study. Their latest research looks at the steady future accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from power stations.

“Despite international efforts to reduce CO2 emissions, total remaining commitments in the global power sector have not declined in a single year since 1950 and are in fact growing rapidly,” the report states.

Massive emissions already committed

Governments worldwide have in principle accepted that greenhouse gas emissions should be reduced and average global warming limited to a rise of 2°C.

At the current pace though, scientists have warned that the world is on track for at least 4° Celsius by the end of the century. That could mean drastic rises in sea levels and catastrophic drought in some areas of the world.

“We are flying a plane that is missing a crucial dial on the instrument panel,” said Socolow. The needed dial would report committed emissions. Right now, as far as emissions are concerned, the only dial on our panel tells us about current emissions, not the emissions that capital investment will bring about in future years.”

In the latest study, scientists asked: once a power station is built, how much carbon dioxide will it emit, and for how long? They assumed a functioning lifetime of 40 years for a fossil fuel plant and then tallied the results.

The fossil fuel-burning stations built worldwide in 2012 alone will produce 19 billion tons of carbon dioxide over their lifetimes. The entire world production of the greenhouse gas from all of the world’s working fossil fuel power stations in 2012 was 14 billion tons.

“Far from solving the problem of climate change, we’re investing heavily in technologies that make the problem worse,” the experts stress.

The US and Europe between them account for 20% of committed emissions, but these commitments have been declining in recent years. Facilities in China and India account for 42% and 8% respectively of all committed future emissions, and these are rapidly growing in number. Two-thirds of emissions are from coal-burning stations ad the share from gas-fired stations had risen to 27% by 2012.

Fossil fuel wind-down not fast enough

Davis says more fossil fuel-burning facilities have to be retired than new ones built. “But worldwide we’ve built more coal-burning power plants in the past decade than in any previous decade, and closures of old plants aren’t keeping pace with this expansion”, he added.

According to Socolow, a high-carbon future is being locked in by the world’s capital investments: “current conventions for reporting data and presenting scenarios for future action need to give greater prominence to these investments,” he said.

The current draft of a summary report to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) due to be released in November and viewed by the Times this week, warns of “severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts” unless carbon emissions are brought under control. The IPCC stresses that human-induced climate change will lead to the devastation of homes and property, a scarcity of food and water and human mass migration, as sea levels rise through warming temperatures and – alas – melting ice.

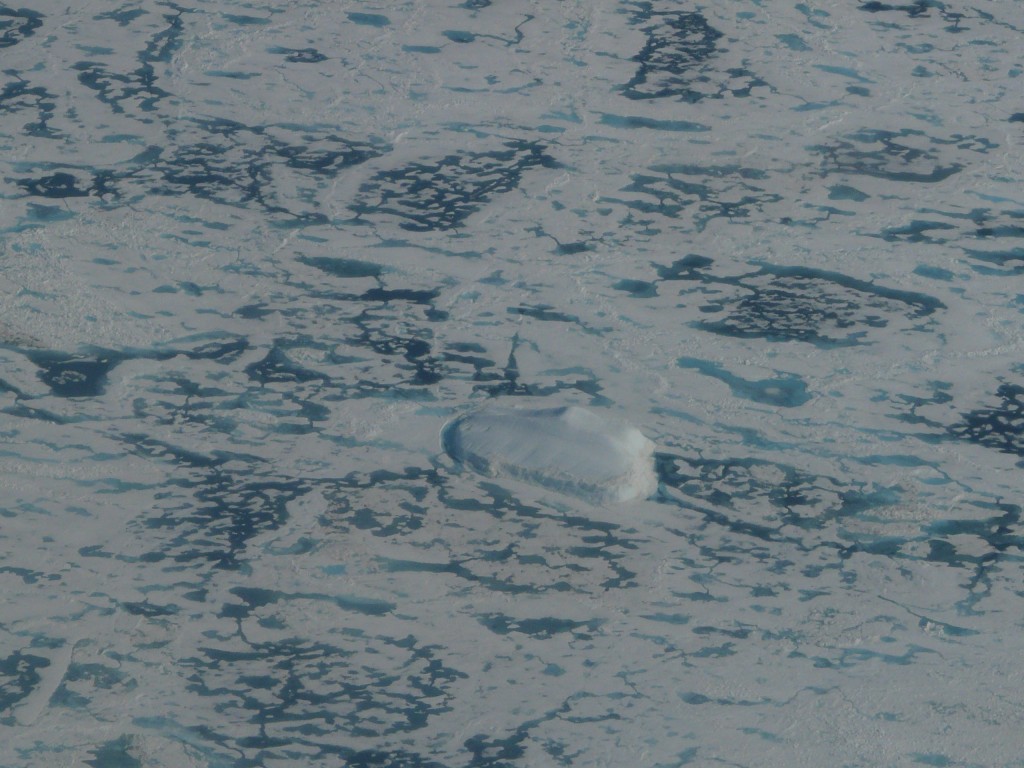

Polar melt confirmed from space

I am disappointed that there was so little mainstream media coverage (please correct me if I am wrong) of a report from a team of scientists from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in Bremerhaven who have analysed just over two years of data from the CryoSat-2 satellite. Their conclusion that the Greenland ice sheet and Antarctica’s glaciers are melting at record pace, dumping some 500 cubic kilometers of ice into the oceans every year, twice as much in the case of Greenland and three times as much in the case of Antarctica, by comparison with 2009 – yes, you read right, we are talking about a very short period for such a dramatic increase in ice loss – should have made more news headlines and not just the science pages.

To understand the scale of that, the researchers say it would be the equivalent of an ice sheet that’s 600 meters thick and covers an area as big as the German city of Hamburg – or, my colleagues here at DW calculate, as big as Singapore.

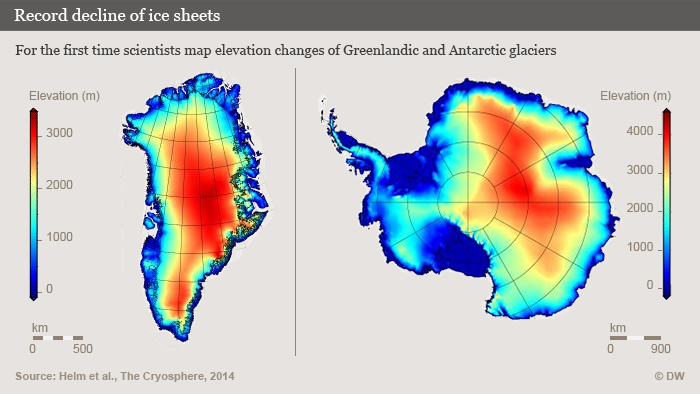

The research team headed by Veit Helm used around two years’ worth of data from the ESA CryoSat-2 satellite to create digital elevation models of Greenland and Antarctica. The results were published in the online magazine of the European Geoscience Union (EGU) The Cryosphere.

“The new elevation maps are snapshots of the current state of the ice sheets,” Helm says. “The elevations are very accurate, to just a few meters in height, and cover close to 16 million square kilometers of the area of the ice sheets.” He says this includes an additional 500,000 square kilometers that weren’t covered in previous elevation models from altimetry.

Space technology shows declining ice mass

Helm and his team analyzed all data from the CryoSat-2 radar altimeter SIRAL in order to come up with the detailed maps. The satellite with this new radar equipment was launched in 2010. Satellite altimeters measure the height of an ice sheet by sending radar or laser pulses which are then reflected by the surface of the glaciers or surrounding areas of water and recorded by the satellite.

The researchers used other satellite data as well to document how elevation has changed between 2011 and 2014.

Rapid ice loss over a short period of time

The team used more than 200 million SIRAL data points for Antarctica and some 14 million data points for Greenland to create the elevation maps. The results show that Greenland alone is losing around 375 cubic kilometers of ice per year.

Compared to data which was collected in 2009, the loss of mass from the Greenland ice sheet has doubled. The rate of ice discharge from the West Antarctic ice sheet tripled during the same period.

I think this is definitely worth talking about. We know the huge implications of polar ice melt for global sea levels. Other research from this year also tells us that, at least in the case of parts of Antarctica, the ice melt is probably irreversible.

We cannot afford to ignore what is happening to the ice sheets. The extent of ice loss in Greenland is particularly dramatic. I am losing patience with those people who respond to studies like this and our reporting on it by saying “but the East Antarctic is gaining volume” and “the Antarctic sea ice has grown”. It is so easy to take things out of context and mix different factors up when trying to understand a very complex system.

I will give the last word here to AWI glaciologist Angelika Humbert, who co-authored the study: “If you combine the two ice sheets (Greenland and Antarctic), they are thinning at a rate of 500 cubic kilometers per year. That is the highest rate observed since altimetry satellite records began about 20 years ago.” It seems to me there is no arguing with that.

Related stories:

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable

Climate change risk to icy East Antarctica

Antarctic Glacier’s retreat unstoppable

Human action speeds glacial melting

It might sound like stating the obvious, but in fact it is not easy to find clear evidence that human behavior is behind the retreat of glaciers being monitored in different parts of the world. Hence my interest in a study just published in the journal Science.

The main problem is that it usually takes decades or even centuries for glaciers to adjust to climate change, says climate researcher Ben Marzeion from the Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics of the University of Innsbruck. He and his team of researchers have just published the results of a study for which they simulated glacier changes during the period from 1851 to 2010 in a model of glacier evolution. They used the recently established “Randolph Glacier Inventory” (RGI) of almost all glaciers worldwide to run the model, which included all glaciers outside Antarctica.

“Melting glaciers are an icon of anthropogenic climate change”, the authors say. However, they stress that the present-day glacier retreat is a mixed response to past and current natural climate variability and “current anthropogenic forcing”. Their modeling shows though that whereas only 25% of global glacier mass loss between 1851 and 2010 can be attributed to human-related causes, the fraction increases to around 69% looking at the period between 1991 and 2010. So human contribution to glacier mass loss is on the increase, the experts write.

Marzeion says the global retreat of glaciers observed today started around the middle of the 19th century at the end of the Little Ice Age, responding both to naturally caused climate change of past centuries (like solar variability), and to human-induced changes. Until now, the real extent of human contribution was unclear. The authors say their latest piece of work provides clear evidence of the human contribution.

Once more I am happy to refer to the Climate News Network, in this case to Tim Radford, for an easy-to-read summary of the main research results and the background. There is no doubt that glaciers are losing mass, retreating uphill and melting at a faster rate, says Radford. He refers to some Andes glaciers and the the Jakobshavn glacier in Greenland, or Sermeq Kujualleq as I prefer to call it, using the indigenous name. Ice Blog followers may remember my own trip to Greenland and that particular glacier. I have also written on the speeding of the melt there on the Ice Blog and on the DW website.

Alpine glacier like these in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, have declined dramatically in recent decades. (I.Quaile)

Radford also refers to ascertaining the melting of alpine glaciers by comparing historic paintings and other documentation with the current ice mass. That decline is something I have observed at first hand in Valais in Switzerland during regular visits over the past 30 years. Look out for a comparative photo gallery of my own pics, when I get time to put it together. Since most of the shots are from the pre-digital era, that will be a time-consuming task.

I also remember a trip to the Visitor Centre of the Begich Boggs glacier in Alaska in 2008. The glacier has already retreated so far you can’t see it at all from the Centre built specially for the purpose of viewing it.

The question until now was how much of all this was caused by natural developments and how much to changes in land use and the emission of greenhouse gases? The latest study supported, among others, by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and the research area Scientific Computing at the University of Innsbruck, has come up with some answers. Since the climate researchers were able to include different factors contributing to climate change in their model, they can differentiate between natural and anthropogenic influences on glacier mass loss

“While we keep factors such as solar variability and volcanic eruptions unchanged, we are able to modify land use changes and greenhouse gas emissions in our models,” says Ben Marzeion, who sums up the study: “In our data we find unambiguous evidence of anthropogenic contribution to glacier mass loss.”

As always, there is still need for further research – and a lot more monitoring. The scientists say the current observation data is insufficient in general to derive any clear results for specific regions, even though anthropogenic influence is detectable in a few regions such as North America and the Alps, where glaciers changes are particularly well documented.

With global glacier retreat contributing to rising sea-levels, changing seasonal water availability and increasing geo-hazards, the study’s conclusions should help put a little more pressure on the world’s decision-makers to get serious about emissions reductions.

Feedback