Search Results for Tag: Alaska

Unbaking Alaska?

When I first went to Alaska in 2008, “Unbaking Alaska“ was the title of the reporting project on how climate change is affecting the region and what the world might be able to do about it. I had to explain the title to my German colleagues, unfamiliar with the “Baked Alaska” dessert, while my North American and British colleagues thought it was a quirky, witty little title.

This week, when I saw an article in the Washington Post entitled “As the Arctic roasts, Alaska bakes in one of its warmest winters ever”, I found the “dessert” had become a little stale .

The thing about “Baked Alaska” is that the ice cream stays cold inside its insulating layer of meringue. Unfortunately, all the information coming out of Alaska and the Arctic in general at the moment, suggest that the ice is definitely not staying frozen.

Too hot for comfort?

In the Washington Post article, Jason Samenow refers to this winter’s “shocking warmth” in the Arctic, some seven degrees above average. Alaska’s temperature, he says, has averaged about 10 degrees above normal, ranking third warmest in records that date back to 1925. Anchorage has found itself with a lack of snow.

“This year’s strong El Nino event, and the associated warmth of the Pacific ocean, is likely partly to blame, along with the cyclical Pacific Decadal Oscillation – which is in its warm phase”, Samenow writes. Lurking in the background is that CO2 we have been pumping out into the atmosphere over the last 100 years or so.

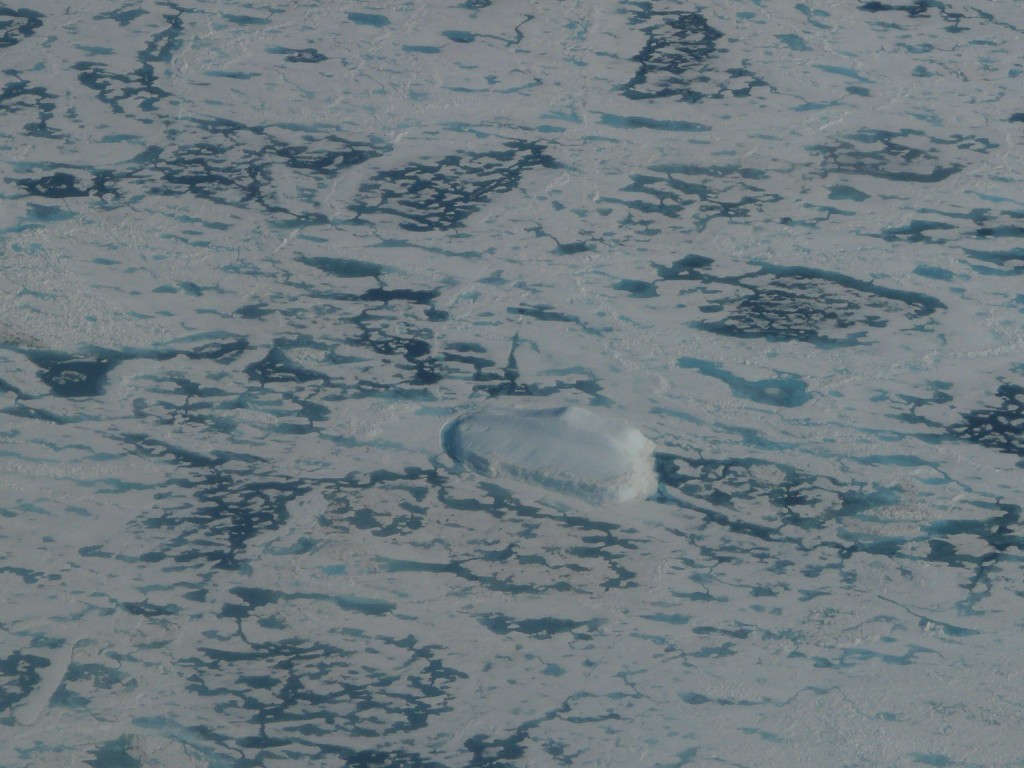

Sea ice on the wane?

Meanwhile, the Arctic sea ice is at a record low. Normally, in the Arctic, the ocean water keeps freezing through the entire winter, creating ice that reaches its maximum extent just before the melt starts in the spring. Not this time.

Yereth Rosen wrote on ADN on Feb. 24th the sea ice had stopped growing for two weeks as of Tuesday. He quotes the NSIDC as saying the ice hit a winter maximum on February 9th and has stalled since.

“If there is no more growth, the Feb. 9 total extent would be a double record that would mean an unprecedented head start on the annual melt season that runs until fall”.

This would be the earliest and the lowest maximum ever. Normally, the ice extent reaches its maximum in early or mid-March.

The most notable lack of winter ice has been near Svalbard, one of my own favourite, icy places.

The experts say it’s too early to say whether this is “it” for this season. There is probably more winter to come. But even if more ice is able to form, it will be very thin.

Toast or sorbet?

Coming back to those culinary clichés: Samenow in the Washington post writes of the second “straight toasty winter” in the “Last Frontier”. The links below his online article are listed under “more baked Alaska”. Amongst them I find the headline: “As Alaska burns, Anchorage sets new records for heat and lack of snow” and “Record heat roasts parts of Alaska”.

The trouble comes when these catchy titles become clichés and somehow stop being quirky.

Don’t we run the risk of not doing justice to the serious threat climate change is posing to the most fragile regions of our planet? Sometimes I worry that the warming of the Arctic is becoming something people take for granted, and, even more dangerous, something we can’t do much about. At times I sense a cynicism creeping in.

I for one will be keeping my oven-baked cake and chilled ice cream separate this weekend.

Is it possible to un-bake Alaska? Food for thought.

Picture gallery on “Baked Alaska” expedition.

Record permafrost erosion in Alaska bodes ill for Arctic infrastructure

At Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the USA, a whole village was lost to erosion (Pic: I.Quaile)

Sitting in my office on the banks of the river Rhine, I am trying to imagine what would happen if the fast-flowing river was eating into the river bank at an average rate of 19 metres per year. It would not belong before our broadcasting headquarters, the UN campus tower and the multi-story Posttower building collapsed, with devastating consequences.

Fortunately, Bonn is not built on permafrost, so we don’t have that particular concern.

Record erosion on riverbank

The record erosion German scientists have been measuring in Alaska probably hasn’t been making the headlines because it is happening in a very sparsely populated area, where no homes or important structures are endangered.

Nevertheless, it certainly provides plenty of food for thought, says permafrost scientist Jens Strauss from the Potsdam-based research unit of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI). He and an international team have measured riverbank, erosion rates which exceed all previous records along the Itkillik River in northern Alaska. In a study published in the journal Geomorphology, the researchers report that the river is eating into the bank at 19 metres per year in a stretch of land where the ground contains a particularly large quantity of ice.

“These results demonstrate that permafrost thawing is not exclusively a slow process, but that its consequences can be felt immediately”, says Strauss.

With colleagues from the USA, Canada and Russia, he investigated the river at a point where it cuts through a plateau, where the sub-surface consists to 80 percent of pure ice and to 20 percent of frozen sediment. In the past, the ground ice, which is between 13,000 and 50,000 years old, stabilized the riverbank zone. The scientists, who have been observing the location for several years, demonstrated that the stabilization mechanisms fail if two factors coincide. That happens when the river carries flowing water over an extended period, and where the riverbank consists of steep cliff, which has a front facing south, and is thus exposed to a lot of direct sunlight.

Minus 12C average no safeguard

The warmer water thaws the permafrost and transports the falling material away, and in spite of a mean annual temperature of minus twelve degrees Celsius, summer sunlight makes it warm enough to send lumps of ice and mud flowing down the slope, according to Michail Kanevskixy from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, lead author of the study.

Overall, between 2007 and 2011, the cliff – which is 700 metres long and 35 metres high – retreated up to 100 metres, resulting in the loss of 31,000 square metres of land area. That is a large area, around 4.3 football fields, the scientists calculate.

In August 2007, they also witnessed how fissures formed within a few days, up to 100 metres long and 13 metres deep.

“Such failures follow a defined pattern”, says Jens Strauss. “First, the river begins to thaw the cliff and scours an overhang at the base. From here, fissures form in the soil following the large ice columns. The block then disconnects from the cliff, piece by piece, and collapses”.

Infrastructure under threat

Although these spectacular events happened far from populated areas and infrastructure, the magnitude of the erosion gives cause for much concern, given the rate at which temperatures are increasing in the Arctic. The scientists want their information to be used in the planning of new settlements, power routes and transport links. They also stress that the erosion impairs water quality on the rivers, which are often used for drinking water.

But what about those areas of the High North where there are settlements and key infrastructure? Russia is starting to get very worried about the effects of increasing permafrost erosion.

Last month the country’s Minister of Natural Resources, Sergey Donsjkoy, expressed grave concern. The Independent Barents Observer quoted the Minister as saying, in an interview with RIA Novosti, he feared the thawing permafrost would undermine the stability of Arctic infrastructure and increase the likelihood of dangerous phenomena like sinkholes. Russia has important oil and gas installations in Arctic regions. Clearly, any damage would have considerable economic implications. There are also whole cities built on permafrost in the Russian north.

System to cool the foundations of a building on permafrost in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland (pic: I.Quaile)

High time to adapt

In 2014, I interviewed Hugues Lantuit, a coastal permafrost geomorphologist with the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, about an integrated database on permafrost temperature being set up as an EU project. He told me it would be very hard to halt this permafrost thaw, and stressed that permafrost underlies 44 percent of the land part of the northern hemisphere.

“The air temperature is warming in the Arctic, and we need to build and adapt infrastructure to these changing conditions. It’s very hard, because permafrost is frozen ground. It contains ice, and sometimes this ice is not distributed evenly under the surface. It’s very hard to predict where it’s going to be, and thus where the impact will be as the permafrost warms and thaws”.

I remember being shocked to see that people in Greenland were having to use refrigeration to keep the foundations of their buildings on permafrost stable. The scale of the problem is clearly much greater in cities like Yakutsk.

Then, of course comes the feedback problem, when thawing permafrost releases the organic carbon stored within it. Let me give the last word to Hugues Lantuit:

“This is a major issue, because it contains a lot of what we call organic carbon, and that is stored in the upper part of permafrost. And if that warms, the carbon is made available to microorganisms that convert it back to carbon dioxide and methane. And we estimate right now that there is twice as much organic carbon in permafrost as there is in the atmosphere. So you can see the scale of the potential impact of warming in the Arctic.”

Paris: A COP-out for Arctic Peoples?

As I write, the climate negotiations have been extended into Saturday. Same procedure as every year? While I still hope the seemingly never-ending bickering will result in a document which will at least signal the end of the fossil fuels era, I cannot help feeling a sense of sadness and regret, that this is all way too late for the Arctic, as I discussed in the last blog post. And I wonder how all this feels to indigenous folk living in the High North, as they see their traditional lifestyles melting away.

On a recent edition of DW’s Living Planet programme, Lakeidra Chavis reported on the effect of melting permafrost on indigenous communities in Alaska. Chatting to a colleague in between times about the story, she told me how moved she was to hear how skulls had been washed up in a river as the permafrost at a burial site thawed.

Climate change impacts the present, future – and past

I had a kind of déjà vu feeling. Back in 2008, in those early days of the Ice Blog, I travelled out to Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the USA, with archaeologist Anne Jensen. We visited the site where a village had had to be re-located because of coastal erosion, with melting permafrost and dwinding sea ice. She told me how she was called up by distraught locals in the middle of the night and asked to help recover the remains of their ancestors before they were washed into the ocean. My colleague here in Bonn was surprised to hear that I had conducted that interview back in 2008. How could this have been known at that time already, yet so little publicized?

Climate change impacts: Jensen at the site of a lost Inupiat village at Point Barrow, 2008 (Pic.: I.Quaile)

Victims or culprits?

While a lot of attention is focused (and rightly so) on the impacts on developing countries, Asia, Africa, rising sea levels, this is an issue a lot of people know very little about. In an article for Cryopolitics Mia Bennet puts her finger on an interesting aspect of all this. The Arctic indigenous peoples are living in industrialized, developed states. That gives them an interesting status, somewhere between being victims and perpetrators of climate warming.

“A discourse of victimization pervades much Western reporting on the Arctic”, she writes. A lot of people in the region tend to blame countries outside the region for climate change. She quotes a study in Nature Climate Change in which researchers found that emissions from Asian countries are the largest single contributor to Arctic warming. But she notes that gas flaring emissions in Russia and forest fires and gas flaring emissions in the Nordic countries are the second two biggest contributors. And these industries are often supported by locals, not least because of the jobs and prosperity they bring.

This brings me back to some encounters I had during that trip to Alaska in 2008 – and others since, with Inuit people employed in the oil sector. They were reluctant to accept that the industries that provided their livelihoods could ultimately be literally eroding the basis of their cultures. Russia, the USA, Canada, Norway – are all countries involved in oil and gas exploitation. Some northern regions are highly dependent on the industries which are warming the climate.

“And for their part, Arctic countries must realize that reducing emissions begins at home on the region’s heavily polluting oil platforms and gas flaring stacks – not in Paris”, says Mia Bennet.

All up to Paris?

The sad truth is that even the two-degree target – or the 1.5 currently being debated – will not have much of an impact on Arctic warming.

Mia Bennet puts it bluntly. “Regardless of whether a positive or negative outcome is reached in Paris at COP 21, it will not dramatically affect the Arctic.”

A delegation of indigenous leaders from the Arctic countries is in Paris at the talks. Both the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the Saami Council have sent delegates, with the aim of highlighting the consequences of a warming climate for the polar regions.

Council representatives are from three distinct Inuit regions: Canada, the USA and Greenland. The Chukotka region of Russia also has a substantial Inuit population, who are not directly represented in Paris, but belong to the Council. The Saami Council has representatives from Finland, Russia, Norway and Sweden. Both sets of delegates are attending as observers, without voting rights.

In a position paper, Inuit Circumpolar Council Chair Okalik Eegeesiak of Canada stresses the Inuit’s deep concern about the impacts of climate change on their cultural, social and economic health.

She describes the Arctic’s sensitive ecosystem as a “canary in the coal mine for global change”. Following that metaphor, the canary must be close to suffocating.

The Inuit representatives in Paris are appealing for stronger measures to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees C. They stress that the land and sea sustain their culture and wildlife, “on which we depend for food security, daily nutrition and overall cultural integrity”.

But ultimately, in a world where altruism seldom plays a part, it may be their other argument – the role of the Arctic in influencing the global climate system – that convinces negotiators of the need to work against global warming. With increasing knowledge and awareness of the extent to which the Arctic influences global processes and thus weather and climate all over the globe, the willingness to take measures to prevent further deterioration of the cryosphere is likely to increase. Whether it will be in time is another question. Any negotiator in Paris who has taken a brief moment off to read this – remember, we are not talking about a remote region with a small population. We are all in this together.

Arctic residents in hot water

At the swimming club last weekend, one of my fellow swimmers complained the water was too warm. She said she couldn’t swim at her usual speed when the temperature in the pool rose even a little bit. It left her feeling tired and lethargic. So how much more dramatic must it be for the tiny creatures at home in cold Arctic waters, when a warm influx changes their surroundings and living conditions.?

The warming of Arctic waters with climate change is likely to produce radical changes in the marine habitats of the High North. Data from long-term observations in the Fram Strait, which researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) have now analysed and published in the journal “Ecological Indicators”, confirms that even a short-term influx of warm water into the Arctic Ocean would suffice to fundamentally impact the local symbiotic communities, from the water’s surface down to the deep seas. They found that this happened between 2005 and 2008.

The deep sea observatory

Over the past 15 years, researchers from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for polar and marine science (AWI) have been keeping an eye on the sensitive marine ecosystem in the Fram Strait, the sea lane between Greenland and Svalbard .The institute operates a deep-sea observatory there, known as “HAUSGARTEN”, which translates literally as house garden. It is actually a network of 21 individual mini research stations. Every summer, scientists pay them a visit and collect water and soil samples. Some of the stations have anchored systems that operate year-round, recording the water temperature and tides, collecting water and soil samples at regular intervals, and capturing the sediments that drift down to the seafloor from the upper water layers.

“This is the only observatory of its kind in the world. There’s no other project in which readings from the surface down to the ocean floor were taken in fixed positions over such a long time – let alone in the polar regions,” says AWI biologist Thomas Soltwedel.

For the current publication, the AWI researcher and his team analysed the first 15 years of the HAUSGARTEN dataset. The Fram Strait is especially interesting for Soltwedel and his colleagues because it represents the only deep juncture in the Arctic Ocean, allowing water masses from the Atlantic to flow into the Arctic to the west of Svalbard. In turn, water and ice floes find their way back out of the Arctic Ocean on the strait’s Greenland side.

Too warm for comfort

Until now, the scientists say it was unclear just how polar marine organisms were responding to the warming of the ocean and shrinking sea-ice cover. Now, the long-term observations show that arctic marine habitats could change radically if subjected to a sustained rise in temperature. The AWI researchers say their most surprising finding is that the thermally induced changes at the ocean surface can rapidly spread to affect life in the deep seas.

Normally the water near the surface, which flows north out of the Atlantic through the Fram Strait, has an average temperature of three degrees Celsius. With the help of their observatory, the AWI researchers were able to establish that from 2005 to 2008 the average temperature of the inflowing water was one to two degrees higher: “In that time, large quantities of warmer water poured into the Arctic Ocean. Since polar organisms have adapted to living in constant cold, this extra heat input hit them like a temperature shock,” Soltwedel explains.

He says the reactions in the ecosystem were correspondingly extreme: “We were able to identify serious changes in various symbiotic communities, from microorganisms and algae to zooplankton.”

Migrating sea creatures

One major change described in the article was the increase in free-swimming conchs and amphipods, which are normally found in the more temperate and subpolar regions of the Atlantic. In contrast, the number of conchs and amphipods in the Arctic dropped significantly.

The researchers also noted a decline in small, hard-shelled diatoms. Prior to the unexpected influx of warm water, they made up roughly 70 per cent of the vegetable plankton in the Fram Strait. But during the warm phase, the foam algae Phaeocystis took their place. A change with consequences, Soltweder explains: “Unlike diatoms, foam algae tend to clump and sink to the ocean floor, where they become a food source. But the sudden rise in available food led to major changes in deep-sea life, including a noticeable increase in the settlement density of benthic organisms.”

If you are not a marine biologist, you may be wondering what that means for the future of the Arctic and why we should be concerned about it. The problem is that all of this affects the Arctic food web.

The scientists can’t say exactly how at this point. But, as with so many other aspects of climate change: “Above all, we’re troubled by the simple fact that the changes have been so rapid, and so far-reaching.”

New residents here to stay

Since the flow of warm water has subsided, the water temperature in the Fram Strait has stabilised – though it is still slightly above the average value from before 2005. Yet some of the changes appear to be there to stay. The conchs from the lower latitudes seem to have made a home for themselves in the Fram Strait.

As usual, the scientists are reluctant to say whether the warm-water influx they monitored is due to climate change or could be part of natural climate fluctuations. They say they need data covering several decades to be more certain.

But either way, the results of the ecological long-term studies clearly show that even short-term changes in ocean temperature can drastically impact life in the Arctic. So it looks like there will certainly be more to come, as the world continues to heat up.

Farewell to ‘Last Ice’ victims in a rapidly warming world

Ice Blog readers may remember the story of the two ice researchers and polar explorers who died when they broke through unexpectedly thin ice in the Canadian Arctic earlier this year. This week I had the chance to join friends and admirers of Marc Cornelissen and Philip de Roo at a ceremony held in their home country, the Netherlands. The unusually warm November weather, with people sitting out eating ice cream, seemed oddly apt for a tribute to two people who died doing climate research.

![]() read more

read more

Feedback