Search Results for Tag: AWI

Arctic investment: still a hot prospect?

As I mentioned in the last post, I talked to various people about the current state of interest in the Arctic, in connection with the ArcticNet conference on “Arctic Change” in Ottawa last week. I would like to share some of the insights I gained with you here on the Ice Blog. With a lot of concerned people still suffering from a kind of mental hangover after the two weeks of UN climate negotiations in Lima, let me also direct you to a commentary I wrote for DW: Lima: a disappointment, but not a surprise. If you expected any action at the meeting which might help stop the Arctic warming, you will have been highly disappointed. If, like me, you think the transition to renewables and emissions reductions we need have to happen outside of and alongside that process, all day and every day, your expectations will not have been so high.

But back to the Arctic itself. With Canada coming to the end of its spell at the helm of the Arctic Council and preparing to hand over the rotating presidency to the USA at the end of the year, the annual conference organized by the research network ArcticNet was bound to attract a lot of interest. More than 1200 leading international Arctic researchers, indigenous leaders, policy makers, NGOs and business people attended the Ottawa gathering to discuss the pressing issues facing the warming Arctic.

Hugues Lantuit from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute is a member of the steering committee. He’s an expert on permafrost and coastal erosion. He told me in an interview that the region had to prepare for greater impacts ,with the latest IPCC report projecting the Arctic would continue to warm at a rate faster than any place on earth. While the retreat of sea ice allows easier access for shipping and more scope for commercial activities, Lantuit is concerned about the thawing of permafrost, a key topic at the Ottawa gathering:

“An extensive part of the circumpolar north is covered with permafrost, and it’s currently warming at a fast pace. A lot of cities are built on permafrost, and the layer that is thawing in the summer is expanding and getting deeper and deeper, which threatens infrastructure.”

Scientists at measuring stations like the one I viisted at Zackenberg, Greenland, measure the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by melting permafrost. (I.Quaile)

Northern communities worried

Residents of northern communities are concerned about the impact of melting permafrost on railways, landing strips and buildings. Lantuit and his colleagues have created an integrated data base for permafrost temperature, with support from the EU. At the Ottawa meeting, he and his colleagues worked on identifying priorities for research, taking into account the needs of communities and stakeholders in the Arctic.

Another key issue on the Ottawa agenda was coastal erosion. Sea ice acts as a protective barrier to the coast, preventing waves from battering the shore and speeding up the thaw of permafrost. With decreasing sea ice in the summer, scientists expect more storms will impact on the coasts of the Arctic. “In some locations, especially in Alaska, we see much greater erosion than there was before”, says Lantuit. This creates a lot of issues: “There is oil and gas infrastructure on the coast, villages, people, also freshwater habitats for migrating caribou, so the coast has a tremendous social and ecological value in the Arctic, and coastal erosion is obviously a threat to settlements and to the features of this social and economical presence in the Arctic.”

Bad news for furred and feathered friends

Amongst the participants at the conference was George Divoky, an ornithologist who has spent every summer of the past 45 years on Cooper Island, off the coast of Barrow, in Arctic Alaska. Divoky monitors a colony of black guillemots that nest on the island in summer. His bird-watching project turned into a climate change observation project as he witnessed major changes in the last four decades:

“Warming first aided the guillemots (1970s and 1980) as the summer snow-free period increased. The size of the breeding colony increased during the initial stages of warming. Continued warming (1990s to present) caused the sea ice to rapidly retreat in July and August when guillemots are feeding nestlings, and the loss of ice reduced the amount and quality of prey resulting in widespread starvation of nestlings.”

The 2014 breeding season on Cooper Island had the lowest number of breeding pairs of Black Guillemots on the island in the last 20 years, Divoky says. Reduced sea ice is increasingly forcing polar bears to seek refuge on the island, eating large numbers of nestlings. Polar bears were rare visitors to the island until 2002.

The Arctic and the global climate

Divoky went to Ottawa to fit his research and experience into the wider context of climate impacts in the Arctic. Researching climate change and its effects are important but of little practical use if the research does not inform government officials and result in policies that address the causes of climate change, Divoky argues.

I asked Hugues Lantuit whether he thought the UN climate conference in Peru could achieve anything that would halt the warming of the Arctic. He said reducing emissions and reducing temperature were the only way to reduce the thaw of permafrost. But he is quite clear about the fact that there is no mitigation strategy in terms of permafrost directly. “You would have to put a blanket over the entire permafrost in the northern hemisphere. This is not possible.”

At the same time, he stressed the key role of the Arctic with regard to the whole world climate: “Permafrost contains a lot of what we call organic carbon, and that is stored in the upper part. And if that warms, the carbon is made available to microorganisms that convert it back to carbon dioxide and methane. And we estimate right now that there is twice as much organic carbon in permafrost as there is in the atmosphere”.

So far, the international community has not been able to take measures to break that vicious circle.

What happened to the Arctic gold rush?

Communities who live and companies that work in the Arctic have to focus on adaptation to the rapid change, says Lantuit. In his eyes, economic activity is increasing, posing new challenges for infrastructure and the environment.

Malte Humpert, the Executive Director of the Arctic Institute, a non-profit think tank based in Washington DC has a different view on the matter. He says while attendance at Arctic conferences and interest in the Arctic is still high, commercial activity has actually been cooling off. “We are seeing a slow-down of investment. Up to this point there has been a lot of studying, a lot of interest being voiced, with representatives from China or South Korea, Japan, Singapore or other actors, arriving at conferences, speaking about grand plans. But up to this point a lot of the talk has been just that.” A lot of activity has been put on hold, says Humpert. He says the “gold rush mentality we saw a few years ago” has weakened. “There was a lot of talk about Arctic shipping initially, then we had oil and gas activity in 2012, north of Alaska, then we had the discussion about minerals in Greenland. The question is now, with the oil price being down below 70$ a barrel, some political uncertainties over the Ukraine, involving the EU and Russia, how will that affect Arctic development?”

Humpert stresses the Arctic does not exist in a vacuum, but has to be seen within the global context. Sanctions on Russia because of the Ukraine crisis have created economic problems for Moscow and limited access to technology it might need for its Arctic activities. “Maybe Arctic development has been oversold and overplayed and will be more of a niche operators’ investment. One could definitely question if there will be this global push into the Arctic.”

Arctic development on ice

Humpert is skeptical that any major development will take place before 2030. He says developing the infrastructure in terms of ports and communications in the remote Arctic region would require billions of dollars of investment, and would have to be a very long-term proposition. It will also depend to a large extent on exactly how climate change affects ice conditions in the Arctic. Climate change can make the climatic conditions in the Arctic more variable. This means that for a temporary period, there might even be more ice, which would block transport routes.

The Arctic Institute says there has actually been a slow down this year in terms of navigation on the northern sea route (NSR) in particular: “The season just closed about a week ago. Last year we had 1.35 million tonnes of cargo being transported along the NSR, this year we had less than 700,000 tonnes, so an almost 50% decrease, just because there was more ice in the way”, says Humpert.

Whether slower development is good news or bad depends on your perspective. The lull in Arctic activity could pre-empt environmental degradation or destruction, says Humpert, and leave scope to consider development of the Arctic in what he calls a 21st century way. Instead of “old-school” thinking about extracting minerals, oil and gas and increasing shipping, there could be a focus on bringing modern, high-speed communications, fiber optics and thinking about renewables, such as wave energy. This would benefit the small populations in the Arctic, the expert argues.

But from the viewpoint of a country like Russia, he adds, where 40 percent of your exports are generated above the Arctic circle, in terms of hydrocarbon resources, the slowdown in Arctic development because of the drop in oil prices and political tensions over Ukraine is very worrying.

So while these developments seem to have brought the Arctic a breathing space, ultimately, the commercialization of the region could be just a matter of time. Ottawa conference organizer Lantuit argues that there has always been activity in the high North. The priority now, he says, must be to ensure international cooperation and additional investment in protecting the environment and maintaining safety in a region where rapid change seems to have become the status quo.

Thick Antarctic ice not sign of cooling

The recent publication of a study on Arctic ice as measured by the “yellow submarine”, an underwater robot, caused a flurry of comments on the “climate hoax” by some of those of a “climate-sceptical” persuasion. I contacted a sea ice physicist at Germany’s AWI Institute for an independent opinion. Here’s the background:

Measurements conducted by an underwater robot have found that Antarctic sea ice is much thicker than previously thought in some places. Much of this floating sea ice is underwater, hidden from the satellites which have been tracking seasonal sea ice for decades. The satellite data is normally validated by drilling into ice floes which can be reached by ship, or visual estimates from the ships themselves. However, it is difficult to reach the thickest ice that way.

Underwater robot below the ice

Over the last four years, an international group of researchers has been mapping the bottom of sea ice in several areas of the Antarctic using an underwater robot, or AUV. It can swim to a depth of some 30 metres (100 feet) and uses sonar directed upwards to survey the bottom of the sea ice. This gave them access to areas where measurements could not be carried out until now.

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, suggests that the average ice thickness could be considerably higher than previous estimates. In three regions surveyed, the robot sub found that deformed, thickened ice accounted for at least half of and as much as 76 percent of the total ice volume, the researchers say.

Climate skepticism vindicated?

While Antarctica’s ice sheet, that is the land ice, is melting and retreating, the extent of the sea ice has been expanding over the last three winters. This has led some who are skeptical about climate change to suggest that it could be evidence that human-made global warming is not happening. But sea-ice physicist Stefan Hendricks, from the Alfred-Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, based in Bremerhaven, Germany, told me in an interview the new measurements were no reason to doubt climate change is happening.

“What our colleagues have shown is that ship-based measurements do not record this really thick ice. That is no surprise to us. It is good that they have found this out, but basically it just tells us that we have to be cautious when it comes to using ship-based data”, Hendricks said.

The sea ice extent in the Antarctic has been growing, while the sea ice in the Arctic, at the northern end of the planet, has decreased dramatically in recent years. Hendricks stresses that the two regions are completely different:

“The Arctic Ocean is surrounded by land, whereas in the Antarctic, the land is in the middle. If the Arctic were not surrounded by land, the ice cover would also be much bigger in winter”, says Hendricks. The increase in Antarctic sea ice in winter can be partly explained by the wind direction, he adds . Ice grows faster, the thinner it is. If it is blown out from shore, for instance into the Indian Ocean, new ice is created very quickly, according to the ice expert. He also warns against comparing what happens to the Arctic in summer to what happens at the southern end of the planet in winter:

“If you look at the cycle over the whole year, your will see that the sea ice in the Antarctic also melts almost completely in summer”.

Valuable data, limited application

Still, the German expert says the new ice measurements from the Antarctic are of major importance to our understanding of how sea ice behaves. But he stresses that the ice floes are on the move all the time. Although the measurements are very exact, the situation is constantly changing ,and the measurements could only be taken at a limited number of spots in what is a huge area of ice.

“The question is how representative is this for the total ice extent? This depends to a very large extent on which ice floe you take. There are large differences between them. The differences are particularly marked if you go further away from land. Close to land, the ice piles up and is deformed and so you get this very thick ice. Further out, you don’t get that”.

The new measurements certainly do not give any reason to be more relaxed about climate warming, says Hendricks. Increased sea ice could have a cooling effect, as ice reflects heat back into space, whereas the sea water absorbs the heat, exacerbating warming. But given that the ice melts again in summer, that effect would be very slight, says the physicist.

Polar melt confirmed from space

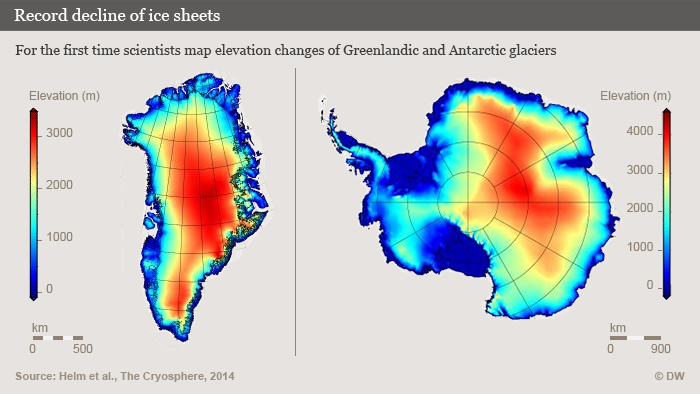

I am disappointed that there was so little mainstream media coverage (please correct me if I am wrong) of a report from a team of scientists from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in Bremerhaven who have analysed just over two years of data from the CryoSat-2 satellite. Their conclusion that the Greenland ice sheet and Antarctica’s glaciers are melting at record pace, dumping some 500 cubic kilometers of ice into the oceans every year, twice as much in the case of Greenland and three times as much in the case of Antarctica, by comparison with 2009 – yes, you read right, we are talking about a very short period for such a dramatic increase in ice loss – should have made more news headlines and not just the science pages.

To understand the scale of that, the researchers say it would be the equivalent of an ice sheet that’s 600 meters thick and covers an area as big as the German city of Hamburg – or, my colleagues here at DW calculate, as big as Singapore.

The research team headed by Veit Helm used around two years’ worth of data from the ESA CryoSat-2 satellite to create digital elevation models of Greenland and Antarctica. The results were published in the online magazine of the European Geoscience Union (EGU) The Cryosphere.

“The new elevation maps are snapshots of the current state of the ice sheets,” Helm says. “The elevations are very accurate, to just a few meters in height, and cover close to 16 million square kilometers of the area of the ice sheets.” He says this includes an additional 500,000 square kilometers that weren’t covered in previous elevation models from altimetry.

Space technology shows declining ice mass

Helm and his team analyzed all data from the CryoSat-2 radar altimeter SIRAL in order to come up with the detailed maps. The satellite with this new radar equipment was launched in 2010. Satellite altimeters measure the height of an ice sheet by sending radar or laser pulses which are then reflected by the surface of the glaciers or surrounding areas of water and recorded by the satellite.

The researchers used other satellite data as well to document how elevation has changed between 2011 and 2014.

Rapid ice loss over a short period of time

The team used more than 200 million SIRAL data points for Antarctica and some 14 million data points for Greenland to create the elevation maps. The results show that Greenland alone is losing around 375 cubic kilometers of ice per year.

Compared to data which was collected in 2009, the loss of mass from the Greenland ice sheet has doubled. The rate of ice discharge from the West Antarctic ice sheet tripled during the same period.

I think this is definitely worth talking about. We know the huge implications of polar ice melt for global sea levels. Other research from this year also tells us that, at least in the case of parts of Antarctica, the ice melt is probably irreversible.

We cannot afford to ignore what is happening to the ice sheets. The extent of ice loss in Greenland is particularly dramatic. I am losing patience with those people who respond to studies like this and our reporting on it by saying “but the East Antarctic is gaining volume” and “the Antarctic sea ice has grown”. It is so easy to take things out of context and mix different factors up when trying to understand a very complex system.

I will give the last word here to AWI glaciologist Angelika Humbert, who co-authored the study: “If you combine the two ice sheets (Greenland and Antarctic), they are thinning at a rate of 500 cubic kilometers per year. That is the highest rate observed since altimetry satellite records began about 20 years ago.” It seems to me there is no arguing with that.

Related stories:

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable

Climate change risk to icy East Antarctica

Antarctic Glacier’s retreat unstoppable

Polar ice tipping points

As I get ready to head up to Tromso for the Arctic Frontiers conference and prepare my accreditation for the next routine round of climate talks here in Bonn in March, I find myself with plenty of food for thought.

It seems like not that long ago that scientists were telling us that although the Arctic is clearly melting fast, there was no need to worry about the Antarctic ice melting. But for the past 15 years or so, scientists have been observing that glaciers in West Antarctica are out of balance. Ice shelves have been breaking off and the calving fronts of glaciers have been retreating, draining huge amounts of ice into the ocean. This week I was interested and concerned to read about the results of a modelling effort, using 3 different types of model, indicating a key Antarctic glacier was melting irreversibly.

(Map courtesy of Deutsche Welle)

The Pine Island Glacier in the Antarctic hit the headlines last year when a giant iceberg broke off it. It is a key glacier because it is actually responsible for some 20 percent of the total ice loss from the region. Now scientists have found the glacier is melting irreversibly – with dramatic consequences for global sea levels. For an article for DW entitled Antarctic’s glacier retreat unstoppable, I interviewed Gael Durand of the French University of Grenoble, one of a team of scientists who have just published the new study: “We show that the Pine Island Glacier will continue to retreat and that this retreat is self-sustaining. That means it is no longer dictated by changes in the ocean or the atmosphere, but is an internal, dynamic process”, Durand told me. This will mean an increasing discharge of ice and a greater contribution to global sea level rise. “It was estimated at around 20 gigatons per year during the last decade, and that will probably increase by a factor of three or five in the coming decade. That means this glacier alone should contribute to the sea level by 3.5 to 10 millimetres a year, accumulating to up to one centimetre sea rise over the next 20 years. For one glacier, that is colossal”, says Durand.

I called up Angelika Humbert from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) to get an expert opinion on the significance of the new research. She told me 1cm over 20 years would be an “extremely high” amount. The glaciologist, who is also working on models for the Pine Island Glacier, stresses that all models include a degree of abstraction and uncertainty. However, her work also indicates that the glacier will make an increasing contribution to sea level rise in the coming years and describes the new study as a “considerable advance on the results of research to date.” Humbert says the results could well be applied to other glaciers of the same type.

Angelika Humbert from AWI took this picture flying over the Pine Island Glacier in a NASA DC8 as part of the IceBridge campaign in 2011

Durand’s new study shows that the glacier is now flowing at a rate and in a way that makes the process irreversible. Even if the air and ocean temperatures cooled off to what they were a hundred years ago – which is in no way likely – Durand is convinced the glacier would not recover. Durand says the study should arouse concern because the glacier has passed a “tipping point”, a much discussed concept in climate science. “That means because of our behaviour, our climate is changing and will continue to change a lot. I think it is one of the first times we are passing these tipping points.”

The scientist compares the situation to that of a cyclist coming down from the top of a mountain and unable to brake: “We have to fear that the retreat will continue, that other glaciers in the region will start to do the same, and that we will have a collapse of this part of the ice shelf. That would take centuries, but it would mean a rise of several metres in sea level.”

The last report by the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change (IPCC) warned of the implications if the glaciers of West Antarctica were to become unstable. “Here,” says Durand, “we have proof that that is already happening with this one.”

At the Arctic Frontiers conference two years back, I heard a lot of interesting discussions about climate tipping points. Professor Carlos Duarte Directorof the Oceans Institute at The University of Western Australia and Research Professor with the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) talked to me at length about tipping points. Let me quote him briefly:

“Tipping Points – or thresholds – are levels of pressures beyond which small response of a property of interest becomes abrupt. Once a system or ecosystem or earth system crosses beyond a threshold, the changes, e.g. in the extent of ice or rate of warming, accelerate greatly, and once the threshold is crossed, it is sometimes very difficult to return to the original state even if pressure is released or reduced.”

We discussed the possible tipping points and warning signs outlined in a key piece of research by Timothy Lenton and others. Some would argue that tipping points have already been crossed in the Arctic region, which is known to be warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the earth. One of Lenton’s other key factors is the West Antarctic ice sheet becoming unstable. Now the “eternal ice” down south could be reaching a kind of “tipping point” in places. Yes, I know this only applies to a particular region of the West Antarctic, but the implications of irreversible glacier melt there are already huge. Greenland and that West Anarctic ice sheet play a key role in storing masses of fresh water, which would have huge implications if they melted. With marine glaciers, like the Pine Island Glaciers, the melt of white ice to expose more dark ocean surface underneath would further increase warming by absorbing solar heat instead of reflecting it back.

With the EU in the news today for considering moving away from binding climate targets, and little progress in sight towards an effective new climate agreement scheduled to be agreed in Paris in 2015, this all puts me in a pensive mood, as I get ready to head north and focus on the implications of the changing climate for “Humans in the Arctic”.

Melting permafrost eroding Siberian coasts

Rising summer temperatures and dwindling Arctic sea ice are eroding the cliffs of Eastern Siberia at an increasing pace. Scientists from AWI, the German Alfred Wegener Institute and the Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research have been evaluating data and aerial photographs of the coastal regions from the last 40 years. As the sea ice recedes more and more from year to year, the cliffs are being undermined by waves. At the same time, the land surface is beginning to sink.

Rising summer temperatures and dwindling Arctic sea ice are eroding the cliffs of Eastern Siberia at an increasing pace. Scientists from AWI, the German Alfred Wegener Institute and the Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research have been evaluating data and aerial photographs of the coastal regions from the last 40 years. As the sea ice recedes more and more from year to year, the cliffs are being undermined by waves. At the same time, the land surface is beginning to sink.

This graphic, courtesy of AWI, shows the interaction between permafrost melt, wave action and coastal erosion

Disappearing island

The research documents warming summers. While the temperatures during the period looked at were higher than zero degrees Celsius on an average of 110 days per year, the scientists counted a total of 127 days in the years 2010 and 2011. In 2012, the number of days with temperatures above freezing increased to 134.The number of summer days on which the sea ice in the southern Laptew Sea vanishes completely is also on the increase. “During the past two decades, there were, on average, fewer than 80 ice-free days in this region per year. During the past three years, however, we counted 96 ice-free days on average. Thus, the waves can nibble at the permafrost coasts for approximately two more weeks each year,“ says AWI permafrost researcher Paul Overduin.

Not only a problem in Siberia

Sea ice plays an important role in protecting coasts from waves. When this barrier is not there, the waves dig deep and erode land away. I saw the results of this first-hand during a trip to Barrow, Alaska, in 2008. I visited sites at Point Barrow, the northernmost point of the United States, where villages had been washed into the sea. On a trip to Greenland in 2009, I was amazed to see buildings being artificially cooled to avoid them sinking into the ground as warming temperatures melt the permafrost.

In the area of Siberia investigated by the German scientists, high cliffs protect the coastline. As the permafrost melts above and waves cut in from below, the cliffs are undermined and break off.

The erosion does not only have an impact on land. It also washes material into the sea, changing the quality of the water. Depending on the kind of erosion and the particular structure of the coast, between 88 and 800 tons of plant-, animal, and microorganism-based carbon are currently washed into the sea per year and kilometer of coastline – materials which were previously sealed in the permafrost, according to the AWI researchers. Once in the water, carbon may turn into carbon dioxide and, as a result, contribute to the acidification of the oceans.

The studies were conducted as part of the PROGRESS project which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. PROGRESS is the acronym for Potsdamer Forschungs- und Technologieverbund für Naturgefahren, Klimawandel und Nachhaltigkeit (Potsdam Research Cluster for Georisk Analysis, Environmental Change and Sustainability).

Feedback