Arctic Winter Impressions

Your Iceblogger is off on a hard-earned break for the next few weeks. I’d like to leave you with some photographic impressions of my winter trip to the Arctic. Thanks again to Norway’s Arctic University in Tromso and the organisers of Arctic Frontiers for the opportunity to visit Svalbard and Tromso at this fascinating time of year. Look out for the next post in April, when spring should be well underway.

Ice floats in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard

Svalbard twilight

- Icicles on the nets aboard the Helmer Hanssen

Winter light outside Tromso

Norway’s Polar Satellite Centre

Polar orbit satellites monitor what’s happening at the ends of the planet – and, of course, the regions in between. Ice conditions, land movement, shipping, pollution – but how does that information actually make its way to the scientists and authorities who evaluate it and use it as a basis for all kinds of decisions?

During my recent visit to Arctic Norway, I had the chance to visit a facility that plays a key role in collecting and disseminating satellite data on the polar regions. On the outskirts of Tromso, Norway’s “Gateway to the Arctic”, there is a satellite ground station, run by KSat, or Kongsberg Satellite Services AS. It is a Norwegian commercial company which provides ground station and earth observation services for polar orbiting satellites. With three interconnected polar ground stations: Tromsø at 69°N, Svalbard (SvalSat) at 78°N and Antarctic TrollSat Station at 72°S, combined with a mid-latitude network of stations in South Africa, Dubai, Singapore and Mauritius, KSAT operates over 70 antennae positioned for access to polar and geostationary orbits.

The Tromso station has contact to 85 satellites every day, and every month the station monitors some 15,000 passes of these satellites overhead.

High demand for high-tech service

High demand for high-tech service

When it comes to which businesses stand to gain from climate change, the providers of satellite data have to rank high on the list. There is a huge demand for data from space, and KSat, it seems, is the biggest company worldwide carrying out this kind of activity.

While I was in town for the Arctic Frontiers conference, two colleagues and I were shown the facility on a beautiful wintry Saturday morning by Jan Petter Pedersen, the Vice President of the company, who is responsible for developing products to expand the business. He studied physics in Tromso and got into satellites during that time, he told us, going on to a PHD in remote sensing. Pedersen has been at KSat for 20 years and says the technology has come a long way in that time. These days, it’s all about remote control via pcs.

We tend to take satellite data for granted. But if you think about it, somebody has to pick up the masses of data from all those satellites circling over the poles and pass the appropriate images to those who need them. Energy, environment, security – these are key areas which make use of the data. In the Tromso station, that data is provided to those who need it more or less in real-time. The company says it can get the data down and sent on to its destination anywhere in the world within 20 minutes. So if you want to detect an oil spill in – say – the Gulf of Mexico? – The chances are, you will get information from this Arctic town.

Some companies own and operate their own satellites, and distribute the data. KSat doesn’t own any satellites, but has agreements to use data. They can access radio data from almost all satellites in operation today.

The USA and Canada are the biggest market for the company’s services, says Pedersen. Then comes Europe, followed by Asia.

The world’s largest polar ground station is the one on the Arctic island of Svalbard. I wasn’t able to visit it during my winter trip – put it must be pretty impressive, with more than 30 antennae.

Satellite monitoring as deterrent to polluters?

When it comes to oil spill detection or monitoring, satellite images play a key role.

Optical sensors have limitations in bad weather, so radar satellite data are of key importance, Pedersen explains. Oil spill detection is the most important of KSat’s earth observation activities. EMSO (European marine Safety Agency) in Lisbon is responsible for European oil spill detection. They get satellite data from 4 providers of satellite data, of which KSat is the biggest. It covers 60% of the waters from the Barents Sea to the Bay of Biscay and the Baltic.

In 2008 there were 10.77 possible reported spills per million km2. In 2011, this was down to 5.08, Pedersen told us. I asked why they talk of “possible”. It seems it is not always possible to be 100 percent sure what the satellite detects is an oil spill. The reliability is somewhere over 60 percent. Pedersen believes the satellite service plays a role in decreasing the figure. As it becomes increasingly well known that satellites are observing and collecting the data, there is a higher awareness that oil spills are being detected. Presumably this is a deterrent to deliberate discharges of oil as well as a key source of information on accidents.

From pirates to icebergs

Another key use for satellite data is in monitoring ship traffic, including detecting, tracking and identifying vessels. This means the authorities can spot illegal activities and inform the coast guards. This helps in finding pirates, for instance.

Tracking icebergs and monitoring ice development have also been aided by the growing availability of satellite data. The NSIDC is one of KSat’s most important customers. They need the data to map the extent and condition of the ice.

Satellite data shows ice changes.

Ships frozen into the ice for research purposes such as the Lance, use satellite images via Tromso. Many other ships use them to chart a course when operating in ice.

Monitoring fishing activities, offshore oil exploration, tracking land movement – all these activities rely on satellite information today.

Pedersen told us the Norwegian capital Oslo is sinking at a rate of 2 cm a year. He also mentioned a landslide risk area outside of Tromso, where a mountain is sliding into the ocean. Ultimately, it will go into the fjord and create a tsunami effect, says Pedersen. That would endanger the settlement. It is moving at 15mm per year. The satellites are keeping an electronic eye on it.

Norway, incidentally, is the country with the highest use of data per person. Most of it is maritime. So it seems fitting that the country should be the location of some of the world’s most important ground stations. There is more to the picturesque Arctic harbour town of Tromso than meets the eye – I can tell you that even without satellite data!

Sharing Arctic ocean data

This week I had an interesting conversation with Professor Karen Wiltshire, who is deputy director of Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research. Last time I talked to Karen was on the German North Sea Island of Helgoland, where she is also head of AWI’s Biological Institute. “Jellyfish and chips” is the theme of the article I wrote then about the institute’s research into the impacts of climate change on the North Sea. Tasty?

This time, I was interviewing her on a wider issue, which also has direct relevance to the Arctic. She has taken over the chair of the “Partnership for Observation of the Global Oceans”, or POGO for short, for the next two years. The Directors of the group just had their annual meeting in Tenerife, on the Canary Islands. POGO, Karen told me, is one of the oldest international organizations set up to link partners interested in observing the world’s oceans. It includes all the world’s key marine institutes, including AWI, Woods Hole, Scripps and institutes from China, Korea and Russia.

The directors meet once a year to discuss issues which can be tackled in a coordinated manner. This includes things like research vessels and monitoring marine protected areas.

Exchanging Arctic Data

But one issue which could bring a lot of benefits in particular to scientists working on the Arctic, is the decision taken at the Tenerife meeting to set up a new platform to link up all the long-term ocean data sets in the world. At the moment, Professor Wiltshire says scientists often don’t know of the existence of a lot of data:

“Some of it is very high quality. For example in northern Russia, in the Arctic Ocean, there’s a lot of data that’s not so easily accessible and available. But if our Russian partners just put a flag on the map saying we have this data, and you can come to us if you need it, it would already help us scientists a lot.

“It’s kind of like making a giant inventory of what’s out there, and of what has been measured for the last hundred years. The next step would be to link important oceans with one another, the Arctic and the Atlantic, and look how they have changed relative to one another, and set up hydrographic models linking these oceans. Those models already exist, but with a better data base we might be able to check the rigor of these models, also relative to the melting ice caps. So the first step is to inventorize what’s out there, and then link data sets, variables and ocean areas.”

Russian data is key

This brings me back to conversations I had on my recent Arctic expedition on the RV Helmer Hanssen. Stig Falk-Petersen, the cruise leader, from Norway’s Arctic University of Tromso, stressed to me just how much research on the Arctic has actually been conducted by Russian scientists. In the past, this was rarely translated, so not available to the majority of the international research community. Things have changed since the end of the Soviet Union, Stig told me, and it became easier for western scientists to work with their Russian colleagues.

“And what we discovered then, was that the Russians know all about our famous polar explorers Nansen and Amundsen, but we new nothing about the Russians. Yet the Russians have a fantastic record of science in the Arctic. Since 1937 they have had these drifting stations, they flew out from Novaya Zemlya and landed on North Pole with four engines, Antonov planes, and established an ice camp. And they drifted out the Fram Strait. They have done this nearly every year until recently. So all we know about the Arctic , the topography, situation of water masses, animal life, benthic life, is actually based on Russian expeditions. And this is still poorly known in the west.”

Modern ice drift

Stig is a great fan of a current drift venture, the Fram 2013-2014 expedition, which is more or less repeating that of the first Russian drift station.

The Norwegian scientists Yngve Kristoffersen and Audun Tholfsen are living and working on their ice drift station, including the hovercraft “Sabvabaa”. It was taken and placed on the ice by the AWI’s research vessel the Polarstern, demonstrating once more the benefits of international cooperation in science. The two men have been taking sediment cores to learn about the polar environment more than 60 million years ago. Since August 2014 they have moved northwards along the submarine Lomonosov Ridge. You can follow their progress online at Geonova. Let me just quote a little from their latest diary:

“The length of Lomonosov Ridge ( ̴1.800 km) is roughly equal to the length of Norway. We have now spent 5 months drifting over the Lomonosov Ridge and been able to get new scientific data over a section which constitutes 1/4 of the total length of the ridge. Our drift shows a pattern with periods of very slow ice drift interrupted by events of fast drift. The fast drift is forced by cells of low surface air pressure moving in to the Arctic Ocean over the Canadian Arctic Islands as lately or through the Fram Strait. As they move in, the wind direction drives the ice to the west. These events, unpredictable on a time scale of months, make it impossible to estimate with some degree of confidence where we will be when it is time for Audun to rotate off in late March/April or when we will approach the ice edge in the Fram Strait.”

The data recorded by the scientists is transferred automatically to the Nansen Centre in Bergen. Stig tells me it includes some spectacular underwater videos going right down to the sea bottom, 2000 metres. He and his colleagues are eagerly awaiting a look at the data.

Data from polar orbit satellites is received and processed at KSAT in Tromso. I was able to visit in January. (Pic. I Quaile)

These days, modern technology, from satellite monitoring to a network of buoys moored around the world’s oceans, some with remote data transmission, provide an increasing amount of new data to be shared and analysed. But to understand properly how the oceans are changing, we need data from the past to compare it with. This brings me back to my interview with Karen Wiltshire.

I asked her whether there wasn‘t a danger that research is not able to keep up with the speed of change? Here is her answer:

“There’s very much the danger of that. One of the most important things is having consistent long-term observation. We need to link up old observations, be it whether somebody stood at the end of a dock and measured salinity for a time, in the late 1800s or so, through to now, where we have modern ways of measuring. These things need to be linked and compared to each other to find out whether what you are looking at is related to a real trend or shift, or is just an anomaly in the system. One has to be very mathematically oriented and creative in doing so. Very often, for example in the Wadden Sea, (off the coasts of Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands), we even use historical anecdotes written down in the annals of churches, for example, to look at how the weather was at a certain time, whether we had an ice winter or not. The more information we have from the past, the better it is. Then we’re in a better position to interpret modern-day data, which might be of very short duration in comparison to the long sets of data out there.”

So the new project to link the world’s oceanic data could be a very important step forward. Here’s to success for the latest POGO venture!

You can listen to the interview with Karen Wiltshire on this week’s Living Planet programme, or by itself here.

Arctic oil – still in the picture

Was it too good to be true? The euphoria over the US administration’s moves to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was dampened somewhat when, just two days later, it released a long-term plan for opening coastal waters to oil and gas exploration, including areas in the Arctic off Alaska. The plan excludes some important ecological and subsistence areas from potential drilling, but it still includes some Arctic areas, including parts of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

Margaret Williams, managing director of WWF US Arctic Programs, told Deutsche Welle, she welcomed in particular the decision to protect the biological hotspot of Hanna Shoal from risky offshore drilling. The Hanna Shoal is a key site for walruses and other animals.

But she stressed other areas of the US Arctic were still subject to oil exploration. The new program will not affect existing leases held by Shell in the Chukchi Sea. The company’s efforts have been the subject of controversy, not least since the grounding of the drill rig Kulluk.

Williams says the problem with the new proposal in general is that it “keeps drilling for oil in the US Arctic offshore in the picture”. With the US poised to take the helm of the Arctic Council, she called for protecting biodiversity to be a top priority for all Arctic nations.

Oil: valuable asset or liability?

It comes as no surprise that Alaskan state politicians and the oil industry promised to fight planned restrictions, saying they were harmful to the economy. But this brings us back to the question of whether the search for new oil in the Arctic makes any sense at all at a time when oil prices are at a record low and the USA is producing plentiful supplies of shale gas.

Bloomberg financial news group quotes financial experts as saying the world’s biggest oil producers do not have “bulletproof business models”, and cites financial cutbacks by BP, Chevrol and Shell:

“The price collapse hobbles a segment of the industry that had already been struggling with years of soaring construction costs, project delays, missed output targets and depressed returns from refining crude into fuels”, analyst Anish Kapadia told Bloomberg.

Climate paradox

Conservation groups stressed the need for a different focus, in the year when the USA has pledged to help create an effective new world climate agreement in Paris in November.

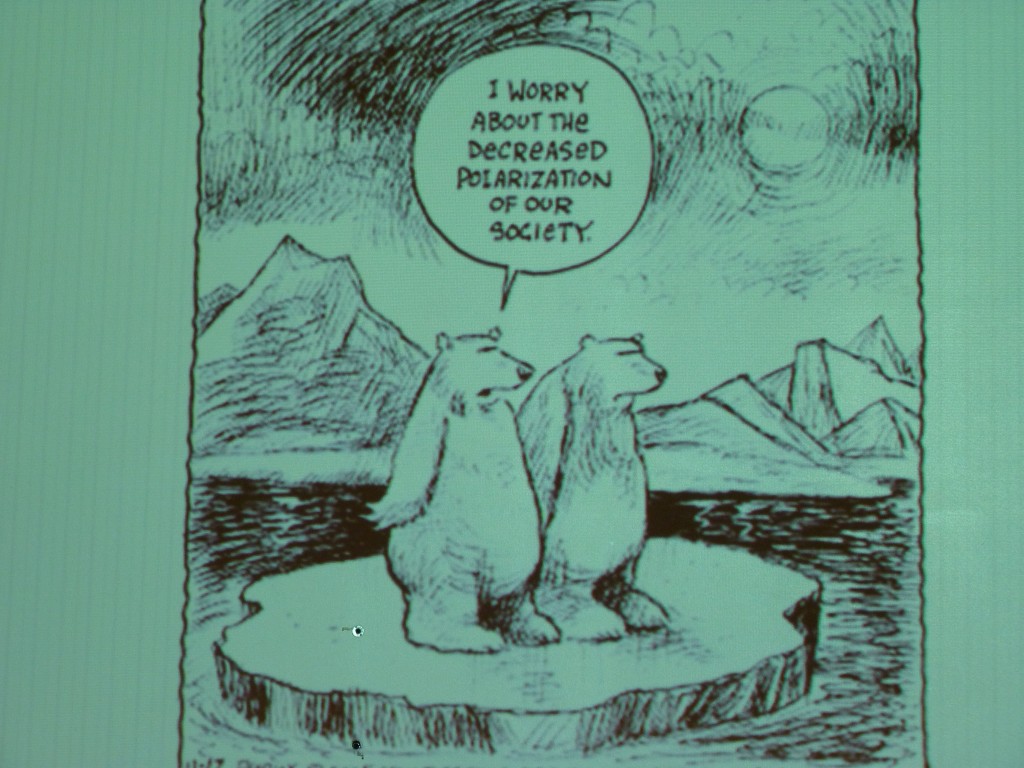

Cartoon by psychologist Per Espen Stoknes, BI Norwegian School of Management.( I photographed it at a workshop on climate change psyschology)

“Rather than opening more of the Arctic and other US coastal waters to drilling for dirty energy, the US needs to ramp-up its transition to a clean energy future. As the Administration works to rally international leaders behind a bold climate pact in 2015, decisions to tap new fossil fuel reserves off our own coasts sends mixed signals about US climate leadership abroad, ” said WWF’s Williams.

We know the Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is in turn of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further.

“We would like to think that we can shift our energy paradigm to clean energy so that we don’t have to take every last bit of oil out of the earth, especially out of the oceans”, said Jackie Savitz from the Oceana Campaign croup.

Studies by the group and by WWF indicate that developing renewable energy technologies such as offshore wind could create more jobs than hanging on to fossil fuel technologies.

Oil spill concern

In addition to the climate paradox of the hunt for new fossil fuels, environmentalists are concerned about the possible impact of an oil spill. Their opposition is not limited to the Arctic. Proposals to open up large areas of coastal waters including some parts of the Atlantic for the first time have also aroused anxiety about possible pollution. But the Arctic is of particular concern because of its remoteness, harsh weather conditions and seasonal ice cover, which is not likely to disappear soon even with rapid climate change:

“Encouraging further oil exploration in this harsh, unpredictable environment at a time when oil companies have no way of cleaning up spills threatens the health of our oceans and local communities they support. When the Deepwater Horizon spilled 210 million gallons of crude oil five years ago, local wildlife, communities and economies were decimated. We cannot allow that to happen in the Arctic or anywhere else,” said WWF expert Williams.

White House senior counsellor John Podesta justified the ban on oil exploration in the ANWR by saying “unfortunately accidents and spills can still happen, and the environmental impacts can sometimes be felt for many years”. The question is – why should this only be applicable in certain areas? Campaigners say it also applies to the other areas now designated by the administration as “OK” for exploration. For the Arctic in particular, limiting exploration to remote offshore areas does not protect the region against the risk of environmental disaster.

Feedback