Cloudy skies speed up Greenland melt

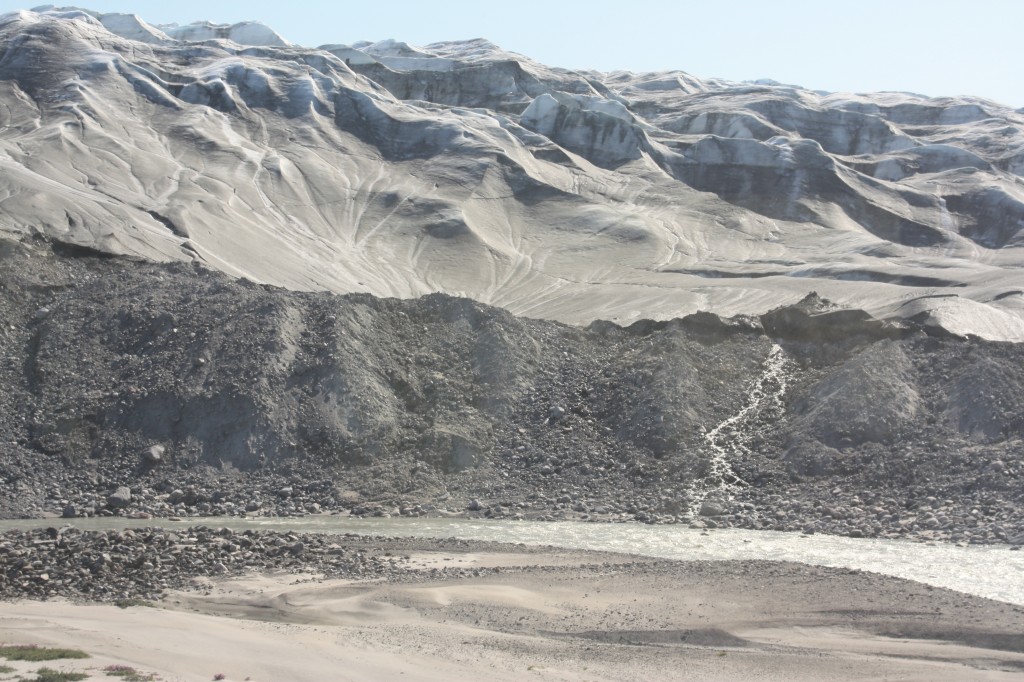

If the Greenland ice sheet were to melt completely, sea level could rise by 7 metres (pic: I.Quaile)

With Greenland known to be one of the main contributors to global sea level rise, mainly through increased meltwater runoff, it is hardly surprising that there is increasing and widespread scientific interest in finding out exactly what factors influence the melting and to what extent. Approximately half of Greenland’s current annual mass loss is attributed to runoff from surface melt.

In my last Ice Blog post, I looked at a study showing that recent atmospheric warming is reducing the ability of some layers of the Greenland ice sheet to store meltwater. That, in turn, can mean runoff is released into the ocean faster than previously assumed, rushing down a kind of icy chute.

Clouds as a night-time warmer

This week, a study led by the University of Leuven in Belgium was published in Nature Communications that suggests that clouds are playing a greater role in this whole process than previously thought. The study concludes that clouds could be enhancing meltwater runoff by about a third relative to clear skies. The scientists used a combination of satellite observations, ground observations, climate model data and snow model simulations.

The impact is not just because the radiative effect of the clouds directly increases surface melt, but because the clouds actually reduce meltwater refreezing at night. They trap heat like a kind of blanket.

Tristan L’Ecuyer, professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and co author of the study, is quoted on the phys. Org science website as saying we could be dealing with another foot of sea level rise around the world over the next 80 years. “Parts of Miami and New York City are less than two feet above sea level; another foot of sea level rise and suddenly you have water in the city”, he warns.

L’Ecuyer stresses that clouds are still not adequately accounted for in climate models. He also stresses that climate models have not kept pace with the rate of melting actually observed on the Greenland ice Sheet.

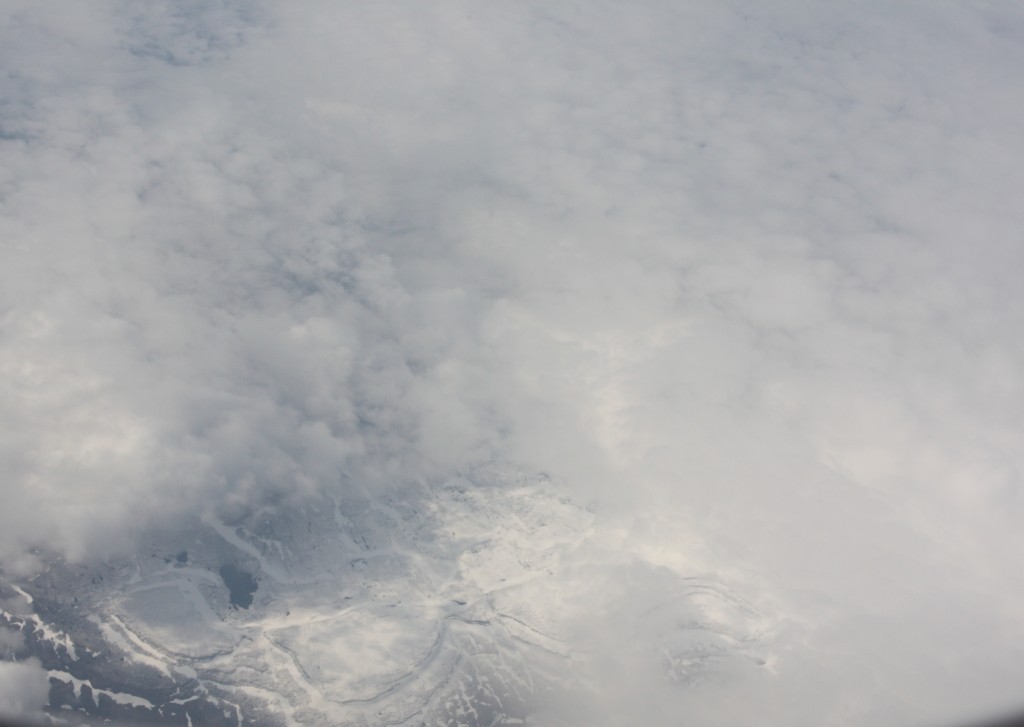

Viewing clouds from above

Improved satellite coverage is improving the situation. L’Eciyer is affiliated with the UW-Madison Space Science and Engineering Center, a pioneer institute in satellite meteorology. Within the last 10 years, NASA has launched two satellites which, L’Ecuyer says, have changed our view of what clouds look like around the planet. He used “X-ray images” of Greenland’s clouds taken by CloudSat and CALIPSP between 2007 and 2010 to determine the structure of clouds, how high they were in the atmosphere, their vertical thickness and whether they were composed of ice or liquid. The Belgian team combined this data with ground-based observations, snow model simulations and climate model data to map the net effect of clouds. This indicated that cloud cover prevents ice that melts in the daytime sunlight from refreezing at night. That, in turn, flows off as meltwater.

The lead author of the study, Kristof Van Tricht from the University of Leuven, who spent six weeks in Madison last year working with L’Ecuyer, uses the sponge image to describe the snowpack. “At night, clear skies make a large amount of meltwater in the sponge refreeze. When the sky is overcast, by contrast, the temperature remains too high and only some of the water refreezes. As a result, the sponge is saturated more quickly and excess meltwater drains away”.

Clouds can cool the earth’s surface by reflecting sunlight back into space. Or they can trap heat like a blanket. On Greenland, scientists agree that clouds primarily act to trap heat.

As with so many climate phenomena, clouds can both affect the climate, and be changed by it. While on the one hand cloud cover can lead to more warming and more meltwater, the resulting effect on the ice sheet can, in turn, affect the cloud cover itself.

The scientists hope studies like this one, making use of advanced satellite technology, can help make future climate models become more accurate by taking this into account. To date, different models disagree on how clouds affect the largest body of ice and so freshwater in the northern hemisphere.

Feedback