Acid Arctic Ocean and Russell Brand?

Is ocean acidification a term you are familiar with? If you are a regular Ice Blog reader, I would like to think you will be. But I am prompted to ask this question because the term came up during a discussion at a weekly evening class I attend, and I was flabbergasted that none of the people there had a clue what it meant. These were all university-educated professionals. That means we in the media have our work cut out for us explaining how climate change is making the seas more acidic, and why this is something we should be worried about.

This incident has reminded me that we journalists have to avoid assuming that everyone is familiar with the terms we use in our coverage on a regular basis. Climate change is the kind of topic where you want to reach a specialist audience, but also the vast majority of the population. We all have to change our habits to reduce CO2 emissions, and we all have to vote for the politicians who have the responsibility for energy and environment policy. That means we need to talk about the problems in a way everybody understands.

I am encouraged to see the BBC website had a longer article on the threat of ocean acidification a few days ago. I don’t think it has made its way into the tabloids though, correct me if I am wrong.

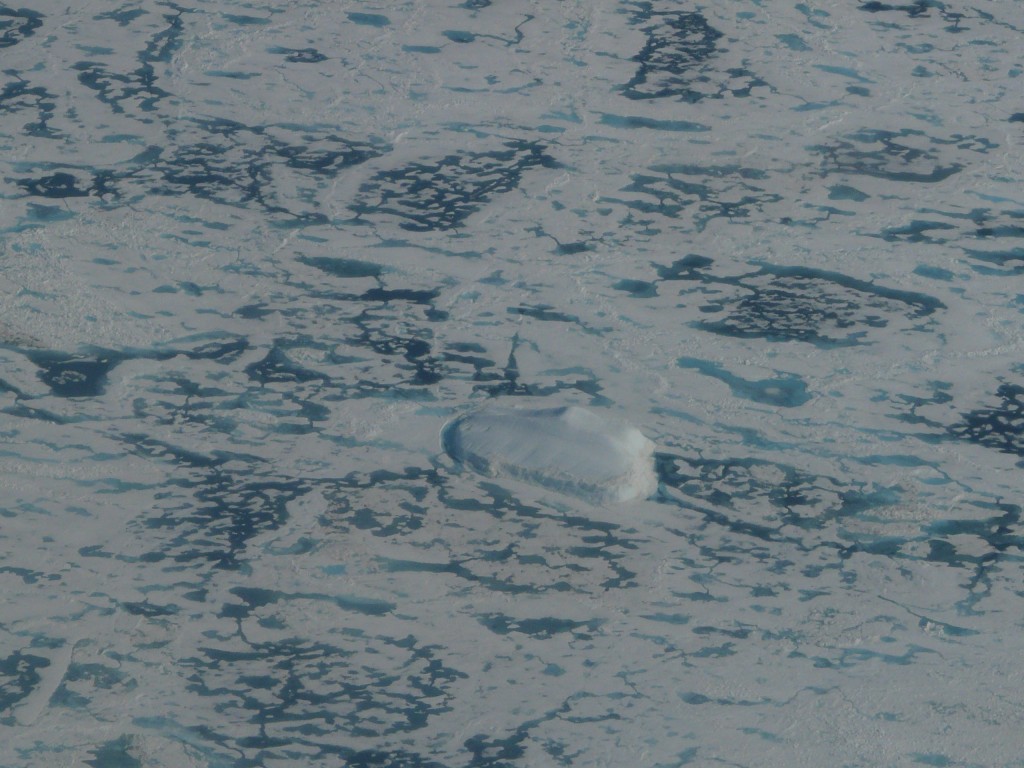

I was made very aware of the issue during a trip to Arctic Spitzbergen in 2010 with a team of scientists monitoring just what happens to the life forms in the sea when it becomes more acidic because it is absorbing so much of the CO2 we emit. The polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

Greenpeace provided scientists with logistic support for the ocean acidification experiments off the coast at Ny Alesund, Spitzbergen. (Pic: Irene Quaile)

Towards the end of last year, I interviewed Professor Alex Rogers from the University of Oxford, who is also the scientific director of the International Programme on the State of the Oceans, which had just published a major study on acidification.

Listen to the interview:

He told me: “The oceans are taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we’re producing at the moment. While this is slowing the rate of earth temperature rise, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in a very profound way.”

Carbon dioxide reacts with sea water to form carbonic acid. Gradually, this makes oceans more acidic.

Threat to marine life

Sea water is already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. According to the IPSO report, it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100.

Over the last 20 years, scientists around the world have been conducting laboratory experiments to find out what that would mean for the flora and fauna of the oceans. Ulf Riebesell of the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, a lead author of the report, conducted the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of the Arctic island of Svalbard in 2010. This was the project I visited.

Giant test-tubes were lowered into the ocean to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades. The experiments showed that increasing acidification decreases the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Scientists say some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Hard times for coastal residents

All this will have severe economic and social consequences. Ultimately, acidification will affect the food chain. Tropical and sub-tropical areas with warm-water corals are going to suffer. Coral reefs are home to numerous species, serve as nurseries for fish and are a valuable tourist attraction. They also protect coastlines against waves and storms.

At the same time, the polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Riebesell told me the experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.” What a horrific prospect.

The Antarctic is already affected. IPSO’s Alex Rogers told me: “We’re seeing instances where we’re finding tiny shelled molluscs, tiny snails that swim in the surface of the oceans, with corroded shells.”

These creatures play a key role in the marine food chain, supporting everything from tiny fish to whales. “One of our primary sources of marine-derived protein is in rapid decline,” says Monty Halls, manager of the UK-based Shark and Coral Conservation Trust. He describes ocean acidification as the “most serious threat to our children’s welfare.” Monty is working to produce video and cartoon material to interest the younger generation in the need to change our behavior to protect marine life.

Two German scientists Antje Funcke and Konstantin Mewes have written and illustrated a children’s story called Tipo and Tessi to make kids aware of the need to protect the ocean. So far, it has only been published in German. The English translation is available, but so far there is a lack of funding for publication.

Vicious circle of climate change

Scientists are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate. That means the more acidic the ocean becomes, the less capacity is has to act as a buffer.

Alex Rogers sees a further problem: “Carbonate structures actually weigh down particular organic carbon. In other words, they help carbon to sink out of the surface layers of the ocean into the deep sea. Anything that interferes in that process can potentially accelerate the rate of CO2 increase in the atmosphere.”

And that would be very dangerous. “The rates of CO2 increase we are seeing at the moment are probably as high as they’ve been for the last 300 million years,” says Rogers.

The IPSO scientists draw an unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions. They say a lot of these major extinction events occurred in connection with high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today.

The BBC article I mentioned earlier also mentions new research by scientists at Exeter University, indicating that increasing acidity creates conditions for animals to take up more coastal pollution, like copper. That would mean not only creatures with calcium-based shells would be endangered.

Find a celebrity champion?

The experts stress that it is not too late to halt the acidification process, although the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. This brings me back to the topics of recent Ice Blog posts: the UN climate negotiations and the need for urgent action. And of course, to the mention in the title above of the British comedian Russell Brand. This relates to another issue I have been writing about recently: the question of celebrity involvement and whether that can help inform people about and interest them in topics like climate change and the acidification of our oceans. My commentary on this, with regard to Leonardo di Caprio at Ban Ki-moon’s September summit in New York, sparked some interesting discussions.

Just this morning I was reading about Russell Brand and how his new book calling for a revolution on all kinds of issues is attracting huge interest. I have noticed that people otherwise completely uninterested in politics and social issues are at least paying some attention because their favourite comedian is talking about them. Maybe we have to get Russell Brand on board. I’m not sure what kind of action he would advocate, but there would certainly be a lot fewer people who could say they’d never heard of ocean acidification.