Search Results for Tag: science

Can we halt Arctic melt? Hard question for UN advisor

I had a very interesting high-profile visitor here at Deutsche Welle this week. Bonn, John Le Carré’s “Small Town in Germany” is this country’s UN city nowadays, home to organizations like the climate secretariat UNFCCC and the Convention on Migratory Species, CMS. This year marks 20 years of the former German capital in that new UN role. Fortunately for me and my colleagues, it brings a lot of interesting people to the city.

The University and the City of Bonn have been running a series of lectures by members of the Scientific Advisory Board of the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon this year, under the heading “Global Solutions for Sustainable Development”. This week, it was the turn of Susan Avery, who was President and Director of the Woodshole Oceanographic Institution in the USA until last year. She has been on the advisory board to Ban Ki-Moon for the last three years and she and the other advisors are just finishing their report, so it was great to have the opportunity to talk in length.

Sea and sky as dancing partners

Her lecture was about the importance of the ocean with regard to climate, but she also talked to me about a whole range of ocean-related issues in an interview to be broadcast on our Living Planet programme, starting next week.

Susan Avery is an atmospheric scientist, (the first to head a major oceanographic institution, she told me). She has a very attractive image to describe how the atmosphere and the ocean relate to each other:

“In our planetary system we have two major fluids, the ocean and the atmosphere, and think of them as two dance partners… moving along, but in order to get a choreographic dance, they have to talk to each other. They do that through the ocean-atmosphere interface, which is wave motion, spray, all the things that help them communicate. These two create different dances… an El Nino dance, or a hurricane dance, for example. In reality what they do together is transport heat, carbon and water, which are the major global cycles in our planetary system.”

Since the onset of industrialization, we humans have been introducing some different steps to the dance, it seems:

“When you take it to the climate scale, we talk a lot about the temperature of the atmosphere, increases associated with the infusion of carbon, that is human produced. The thing is that the extra carbon dioxide that gets released into the atmosphere through our fossil fuels and deforestation is associated with extra heat. Of the carbon dioxide we release into the atmosphere, half will stay in the atmosphere, 25% will go into the ocean, 25% will be taken up by the land. But if you look at the heating or warming, 93% of the extra warming is actually in the ocean. There are only very small amounts in the atmosphere.”

Centuries of warming pre-programmed

That means a huge amount of heat is actually being stored in our seas:

“And you can understand why, because the atmosphere is a gas, the ocean is a mass of liquid, which covers two thirds of our planet, and it has a huge heat capacity to store that, but that heat doesn’t just stay at the surface. So (..) when you only talk about heat and temperatures at the surface, you’re ignoring what’s happening below the surface in the ocean, and once the ocean gets heated it’s not going to stay there, because there is this fluid motion. So we’re getting to see greater and greater temperature increases at greater and greater depths. And once that heat gets into the ocean, it can stay there for centuries. Whereas in the upper ocean, it might stay 40 or 50 years, when you get into the deeper parts, because of the density and capacity, it stays there for a long time.”

So, she explained, the carbon dioxide we’ve put into the atmosphere already – and the heating associated with that – means that “we’re already pre-destined for a certain amount of global temperature increase. Many people say we have already pre-destined at least one and a half degree, some will say almost two degrees.”

Now if that is not a sobering thought.

And on top of that comes the acidification of the oceans caused by the extra carbon dioxide, which is playing havoc with coral reef systems and shell-based ocean life forms.

“This is really critical, because it attacks a lot of the base of the food chain for a lot of these eco-systems”.

“What’s in the Arctic is not staying in the Arctic”

Susan Avery’s work has included research on the Arctic and Antarctic, so of course I took the opportunity to ask how she sees all this affecting the polar regions.

She explained how the rapid increase in ice melt in the Arctic – both sea-ice and land ice – caused by atmospheric warming above and warmer ocean waters below, is of great concern for two reasons. The more obvious one is the contribution of land ice melt to sea-level-rise. The other, she explained, is that the melting of the land-based ice results in “a freshening of certain parts of the ocean, so particularly the sub-polar north Atlantic, so you have a potential for interfacing with our normal thermohaline circulation systems which could dramatically change that.” The changes in salinity currently being observed, are a “signal that the water cycle is becoming more vigorous”. This, of course, has major implications for ocean circulation and, in turn, the climate, not just in the region where the ice has been melting:

“What’s in the Arctic is not staying in the Arctic. What’s in the Antarctic is not staying in the Antarctic. I would say the polar regions are regions where we don’t have a lot of time before we see major, massive changes”.

What I find particularly worrying is that Susan Avery confirmed there is still so much we do not know about what is happening in the polar regions and in the ocean in general.

“We really need to get our observations and science and models working together”, she told me. “The new knowledge we have created on processes in the Arctic has to be incorporated into climate system models”.

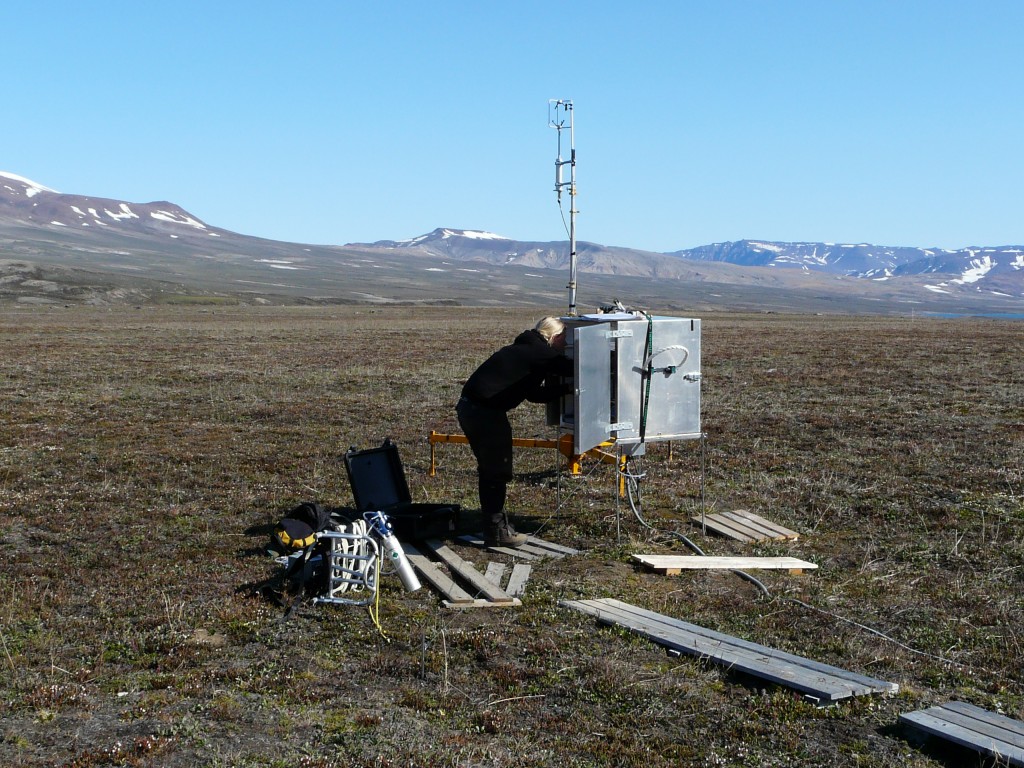

Satellite data ( KSAT site in in Tromso) helps, but cannot penetrate deep ocean, Avery says. (Pic. I Quaile)

Paris and the poles

So, given that temperature rise of 1,5 to two degrees Celsius could already be a “given”, and the Arctic is being affected much faster and more strongly than the planet on average, is there any real hope that we can hold up these developments and halt the melting of ice in the Arctic? This was clearly a very difficult question for my guest. She told me she had been very relieved that the Paris Climate Agreement was signed and was sure humankind could still “make things better”. But when I asked whether we will really be able to reverse what is happening in the Arctic or halt climate change in the Antarctic, this was what she replied:

“I don’t have an answer, to be honest. I think we’re still learning a lot about the Arctic and its interface with lower latitudes, how that water basically changes circulation systems, and on what scale. But I think what’s really critically needed right now to get a better sense of the evolution of the Arctic, and of sea level rise, is a real concerted observing network. We know so little, about the Arctic, the life forms underneath the ice. We have the technology. What I really see now is a confluence of new technologies, new analytical approaches, new ways to do ocean science, and all it takes is money to really get those robots there, get the genomic studies that you need, the analysis. We are at the stage where we can do so much, to further our understanding, and I would really put a lot into the Arctic right now, if I had the money to do so.”

Me too, Susan.

Ice: the final frontier?

Investigating the undersea secrets of the Arctic night from the research vessel Helmer Hanssen (Pic: I.Quaile)

This brings us back to a key problem I have worried about ever since I started to work on how climate change is affecting the Arctic. That change is speeding up so fast, it is virtually impossible for our research to keep pace. As Susan Avery put it:

“The Arctic will be a major economic zone, we’ve already seen the North-West Passage through the Arctic waters, we’re going to see migration of certain fisheries around the world – and we don’t even know completely what kind of biological life we have below that ice. We have the ability to get underneath the ice now. I call these the frontiers, of the ocean, and that includes looking under ice.”

I am reminded of my trip on board the Helmer Hanssen last year, accompanying a research mission to find out what happens under that ice and down in the deep ocean during the cold, dark season.

(Listen to the audio feature here). There is still so much we do not know about life in the ocean – and it might disappear before we even knew it was there.

Why Brexit bodes ill for the Arctic

EU headquarters in Brussels. The Arctic is high on the European Union’s foreign policy agenda. The EU Council just published new Conclusions on the Arctic (Pic: I.Quaile)

Today’s Ice Blog post was going to be about permafrost, with the the International Conference on Permafrost drawing to a close after a week in Potsdam outside Berlin today. But the Brexit decision is casting a shadow over a lot of things today – and that includes the international spirit of cooperation that is the key to successfully tackling the all-embracing challenge of climate change and its destructive impacts on Arctic ice and permafrost. And while the permafrost is melting, the political atmosphere and social climate here in Europe are definitely becoming much colder.

British breakaway bad news for science

Not that the decision in itself will necessarily have a direct, immediate impact. Scientific research will go on in Britain and other parts of the world regardless of whether or not the country is a member of the European Union. The UK has a long tradition of polar exploration and research. But research relies on international cooperation – and the EU has become one of the key funders of Arctic research in recent decades.

British Arctic marine biologist collaborating with Dutch colleagues. (Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen, Pic: I.Quaile)

Leading scientists including Stephen Hawking have said a Brexit would be a disaster for UK science in general.

A group of 13 Nobel prize-winning scientists have also warned that leaving the EU would pose a “key risk” to British science. The group, which includes Peter Higgs, who predicted the existence of the Higgs boson particle, say losing EU funding would put UK research “in jeopardy”.

“Inside the EU, Britain helps steer the biggest scientific powerhouse in the world”, the group claim in a letter to the British Daily Telegraph.

While the other side insisted leaving the EU would not be damaging, the majority of scientists appear to be in favour of Britain remaining in the EU. 83% of scientists polled opposed Brexit.

International “give-and-take”

It is not just a matter of EU funding for British science. The scientist group stressed that British scientists should also be involved in the EU as a hub of innovation and research. They say more than one in five of the world’s researchers move freely within the EU boundaries.

Restricting this free movement is one of the key aims of the Brexit campaign. As a British journalist working in Germany, I have experienced the benefits of being able to travel, study and work in other European countries for many years.

Future generations bear the brunt

The majority of young people who voted apparently voted to stay in the EU. This is the generation that stands to gain or lose by the Brexit decision. If I think of all the dedicated young scientists from Britain and other countries I have interviewed over the years, working across borders on issues that are certainly not limited to one local area, it makes me sad and even angry that they stand to lose out because of a campaign that was based on negative sentiments like the desire to keep foreign workers and refugees out of Britain, or vague and unfounded claims that everything that does not work in Britain is the fault of the EU. No, it’s not perfect, but I doubt that many of the arrangements that protect nature in the UK and other European countries would be in place without the involvement of Brussels. And how is a body like the EU going to change and reform if not through pressure from within?

Anyone who cares about the environment knows that without international cooperation, it is not possible to protect our air, land, water and atmosphere against abuse and pollution.

Measuring CO2 emissions from summer permafrost at Zackenberg, Greenland. GLobal emissions warm the Arctic, melting permafrost reinforces the global warming effect. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Not just about money

In an article for the MIT Technology Review, Debora MacKenzie says the EU budgeted 74.8 billion euros for research from 2014 to 2020. Brexiters, she writes, say British taxpayers should simply keep their contribution and spend it at home:

“They’d take a serious loss if they did. Britain punches above its weight in research, generating 16 percent of top-impact papers worldwide, so its grant applications are well received in Brussels. Between 2007 and 2013, it paid 5.4 billion euros into the EU research budget but got 8.8 billion euros back in grants. British labs depend on that for a quarter of public research funds, a share that has increased in recent years. A cut in that funding after Brexit could drag down every field in which British research is prominent—which is most of them.”

MacKenzie also quotes Mike Galsworthy, a health-care researcher at University College London who launched the social-media campaign Scientists for EU:

“It’s not just funding, EU support catalyzes international collaboration.” Galsworthy puts his finger on a key issue here:

“The EU funds research partly to boost European integration: for most programs you need collaborators in other EU countries to get a grant. This isn’t a bad thing, as collaborative work tends to mean more and higher-impact publications.”

Indeed.

International team measure ocean acidification off Spitsbergen, as part of EU EPOCA programme. (Pic.: I.Quaile)

One shared world

The spirit behind the vote to leave the EU is to a large extent based on nationalism and xenophobia. If it were to prevail, it would lead us backwards and result in fragmentation. That has to be bad news for those of us who believe in working together across borders for the greater good of the planet as a whole. Climate warming is a global phenomenon. We need to work together to tackle it. The icy regions of the northern hemisphere may belong geographically to individual countries like the USA, Canada, Russia or Norway. But in today’s industrialized, globalised world, no single player alone can stop the ice from melting. Or regulate the increased fishing, shipping or exploitation of natural resources in once pristine areas now becoming rapidly accessible.

Arctic sea ice, Greenland and Europe’s weird weather

As I write this, I am sitting in a short-sleeved shirt with the window open, enjoying an unusually warm start to the month of May. It’s around 27 degrees Celsius in this part of Germany, pleasant, but somewhat unusual at this time. The first four months of this year have been the hottest of any year on record, according to satellite data.

The Arctic is not the first place people tend to think of when it comes to explaining weather that is warmer – as opposed to colder – than usual in other parts of the globe. But several recent studies have increased the evidence that what is happening in the far North is playing a key role in creating unusual weather patterns further south – and that includes heat, at times.

Why sea ice matters

The Arctic has been known for a long time to be warming at least twice as fast as the earth as a whole. As discussed here on the Ice Blog, the past winter was a record one for the Arctic, including its sea ice. The winter sea ice cover reached a record low. Some scientists say the prerequisites are in place for 2016 to see the lowest sea ice extent ever.

Several recent studies have increased the evidence that these variations in the Arctic sea ice cover are strongly linked to the accelerating loss of Greenland’s land ice, and to extreme weather in North America an Europe.

“Has Arctic Sea Ice Loss Contributed to Increased Surface Melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet”, by Liu, Francis et.al, published in the journal of the American Meteorological Society, comes to the conclusion: “Reduced summer sea ice favors stronger and more frequent occurrences of blocking-high pressure events over Greenland.” The thesis is that the lack of summer sea ice (and resulting warming of the ocean, as the white cover which insulates it and reflects heat back into space disappears and is replaced by a darker surface that absorbs more heat) increases occurrences of high pressure systems which get “ stuck and act like a brick wall, “blocking” the weather from changing”, as Joe Romm puts it in an article on “Climate Progress”.

Everything is connected

The study abstract says the researchers found “a positive feedback between the variability in the extent of summer Arctic sea ice and melt area of the summer Greenland ice sheet, which affects the Greenland ice sheet mass balance”. As Romm sums it up:“that’s why we have been seeing both more blocking events over Greenland and faster ice melt.”

He quotes co-author Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University, New Jersey, explaining how these “blocks” can lead to additional surface melt on the Greenland ice sheet, as well as “persistent weather patterns both upstream (North America) and downstream (Europe) of the block.

“Persistent weather can result in extreme events, such as prolonged heat waves, flooding, and droughts, all of which have repeatedly reared their heads more frequently in recent years”, Romm concludes.

“Greenland melt linked to weird weather in Europe and USA” is the headline of an article by Catherine Jex in Science Nordic. People are usually interested in changes in the Greenland ice sheet because of its importance for global sea level, which could rise by around seven metres if it were to melt completely. But Jex also draws attention to the significance of changes to the Greenland ice for the Earth’s climate system as a whole.

The jet stream

“Some scientists think that we are already witnessing the effects of a warmer Arctic by way of changes to the polar jet stream. While an ice-free Arctic Ocean could have big impacts to weather throughout the US and Europe by the end of this century”.

She also notes some scientists warning of “superstorms”, if melt water from Greenland were eventually to shut down ocean circulation in the North Atlantic.

The site contains an interactive map to indicate how changes in Greenland and the Arctic could be driving changes in global climate and environment.

The jet streams drive weather systems in a west-east direction in the northern hemisphere. They are influenced by the difference in temperature between cold Arctic air and warmer mid-latitudes. With the Arctic warming faster than the rest of the planet, this temperature contrast is shrinking, and scientists say the jet streams are weakening.

Jex quotes meteorologist Michael Tjernström, from Stockholm University, Sweden: “Climatology of the last five years shows that the jet has weakened,” says. Its effect on weather around the world is a hot topic.

“We’ve had strange weather for a couple of years. But it’s difficult to say exactly why.”

One explanation, Jex writes, is that a weak jet stream meanders in great loops, which can bring extremes in either cold dry polar air or warmer wetter air from the south, depending on which side of the loop you find yourself. If the jet stream gets “stuck” in this kind of configuration, these extreme conditions can persist for days or even weeks.

Experts have attributed extreme events like the record cold on the east coast of the USA in early 2015, a record warm winter later the same year, and the summer heat waves and mild wet winters with exceptional flooding in the UK to these kind of “kinks” in the jet stream.

Greenland and the ocean

The changes to Greenland’s vast land ice sheet also have consequences for ocean circulation, because they mean an influx of the cold fresh water flowing into the salty sea. And the sea off the east coast of Greenland plays a key role in the movement of water, transporting heat to different parts of the world’s oceans and influencing atmospheric circulation and weather systems.

There have often been “catastrophe scenarios” suggesting the Gulf Steam, which brings warm water and weather from the tropics to the USA and Europe could ultimately be halted, leading to a new ice age. (Remember the “Day after Tomorrow?)

Although this extreme scenario is currently considered unlikely, research does suggest that the major influx of fresh water from melting ice in Greenland and other parts of the Arctic could slow the circulation and result in cooler temperatures in north western Europe.

Jex goes into the theory of a “cold blob” of ocean just south of Greenland, where melt water from the ice sheet accumulates. Some scientists say this indicates that ocean circulation is already slowing down. The “blob” appeared in global temperature maps in 2014. While the rest of the world saw record breaking warm temperatures, this patch of ocean remained unusually cold.

According to a recent study led by James Hansen, from Columbia University, USA, the ‘cold blob’ could become a permanent feature of the North Atlantic by the middle of this century. Hansen and his colleagues claim that a persistent ‘cold blob’ and a full shut down of North Atlantic Ocean circulation could lead to so-called ‘superstorms’ throughout the Atlantic. And there is geological evidence that this has happened before, they say. But the paper was controversial and many climate scientists questioned the strength of the evidence.

However, some scientists already attribute western Europe’s warm and wet winter of 2015 to the “cold blob”, Jex notes, which may have altered the strength and direction of storms via the jet stream.

The good old British weather

The UK’s Independent goes into a new study by researchers at Sheffield University, which indicates soaring temperatures in Greenland are causing storms and floods in Britain. The Independent’s author Ian Johnston says the study “provides further evidence climate change is already happening”.

It never ceases to amaze me that evidence is still being sought for that, but, clearly, there are still those who are yet to be convinced our human behavior is changing the world’s climate. So every bit of scientific evidence helps – especially if it relates to that all-time favourite topic of the weather.

The study also looks at the static areas of high pressure blocking the jet stream. With amazing temperature rises of up to ten degrees Celsius during winter on the west coast of Greenland in just two decades, it is not hard to imagine how this can effect the jet stream, and so our weather in the northern hemisphere.” If forced to go south, the jet stream picks up warm and wet air – and Britain can expect heavy rain and flooding. If forced north, the UK is likely to be hit by cold air from the Arctic”, Johnston writes.

The article quotes Professor Edward Hanna from the University of Sheffield, lead author of a paper about the research published in the International Journal of Climatology, and says seven of the strongest 11 blocking effects in the last 165 years had taken place since 2007, resulting in unusually wet weather in the UK in the summers of 2007 and 2012.

Hanna told the Independent computer models used 10 to 15 years ago to predict the extent of sea ice in the Arctic had significantly underestimated how quickly the region would warm.

“It’s very interesting to look at the observed changes in the Arctic … the actual observations are showing far more dramatic changes than the computer models,” Professor Hanna said.

“You do get sudden starts and jumps. It’s the sudden changes that can take us by surprise and there certainly does seem to have been an increase in extreme weather in certain places.”

Drawing conclusions (or not?)

In the Washington Post, (reprinted on Alaska Dispatch News) Chelsea Harvey sums up the conclusions of the latest research in an article entitled “Dominoes fall: Vanishing Arctic ice shifts jet stream, which melts Greenland glaciers”:

“There are a more complex set of variables affecting the ice sheet than experts had imagined. A recent set of scientific papers have proposed a critical connection between sharp declines in Arctic sea ice and changes in the atmosphere, which they say are not only affecting ice melt in Greenland, but also weather patterns all over the North Atlantic”.

So what do we learn from all of this? Sometimes I ask myself how many times we have to hear a message before we really take it in and decide to do something about it.

Here in Bonn, not far from the office where I am sitting now, the first round of UN climate talks since the Paris Agreement at the end of last year will be kicking off this coming weekend. The aim is to stop the rise in global temperature from going about two, preferably 1.5 degrees C. We have already passed the one degree mark. In an interview with the Guardian this week, the head of the IPCC Hoesung Lee says it is still possible to keep below two degrees, although the costs could be “phenomenal”. But many scientists and other experts are increasingly dubious about whether emissions can really peak in time to achieve the goal. Current commitments by countries to emissions reductions still leave us on the track for three degrees at least.

The concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is, as the Guardian puts it, “teetering on the brink of no return”, which the landmark 400 ppm measured for the first time at the Australian station at Cape Grim and unlikely to go below the mark again at the Mauna Loa station in Hawaii.

On my desk, I have a book entitled “Arctic Tipping Points”, by Carlos M. Duarte and Paul Wassmann. It was published in 2011. Before that, Professor Duarte had explained the global significance of what is happening in the Arctic to me

at an Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromso, Norway. How much more evidence do we need? Science takes a long time to research, evaluate and publish solid evidence of change and its consequences, with complex review processes. If politicians delay much longer, the pace of climate change will be so fast that action to avert the worst cannot keep up. Meanwhile, that Arctic ice keeps dwindling – and I sense another major storm on the approach.

Arctic future: not so permafrost

“A glance into the future of the Arctic” was the title of a press release I received from the Alfred Wegener Institute this week, relating to the permafrost landscape.

“Thawing ice wedges substantially change the permafrost landscape” was the sub-title.

“I felt the earth move under my feet…” was the song line that came to my mind.

The study was led by Anna Liljedahl of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. And Fairbanks is, indeed, where I would like to have been this past week, with Arctic Science Summit Week taking place.

Arctic Council in Fairbanks

Clearly the Arctic Council thought the same and actually managed to put their wish into practice by holding a meeting of the Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) there from March 15th to 17th. The agenda focused to a large extent, it seems, on climate change, and “placing the Council’s overall work on climate change in the context of the COP21 climate agreement” reached in Paris in December, according to a media release.

“The Council needs to consider how it can continue to evolve to meet the new challenges of the Arctic, particularly in light of the Paris Agreement on climate change. We took some steps in that direction this week”, said Ambassador David Balton, Chair of the SAOs.

Now what exactly does that mean? The Working Groups reported “progress on specific elements”. They include the release of a new report on the Arctic freshwater system in a changing climate, “cross-cutting efforts aimed at preventing the introduction of invasive alien species”, strengthening the region’s search and rescue capacity, efforts to support a pan-Arctic network of marine protected areas and promoting “community-based Arctic leadership on renewable energy microgrids”. I suppose those could be part of the process. Clearly there are a lot of interesting things going on.

NOAA’S latest – not so cheery

Against the background of NOAA’s latest revelations on global temperature development, though, they may have to speed up the pace. The combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for February 2016 was the highest for February in the 137-year period of record, NOAA reports, at 1.21°C (2.18°F) above the 20th century average of 12.1°C (53.9°F). This was not only the highest for February in the 1880–2016 record—surpassing the previous record set in 2015 by 0.33°C / 0.59°F—but it surpassed the all-time monthly record set just two months ago in December 2015 by 0.09°C (0.16°F).

Overall, the six highest monthly temperature departures in the record have all occurred in the past six months. February 2016 also marks the 10th consecutive month a monthly global temperature record has been broken. The average global temperature across land surfaces was 2.31°C (4.16°F) above the 20th century average of 3.2°C (37.8°F), the highest February temperature on record, surpassing the previous records set in 1998 and 2015 by 0.63°C (1.13°F) and surpassing the all-time single-month record set in March 2008 by 0.43°C (0.77°).

Here in Germany, the temperature was 3.0°C (5.4°F) above the 1961–1990 average for February. NOAA attributes it to a large extent to strong west and southwest winds. Now that is a big difference, and I can certainly see it in nature all around. But the difference was more than double that in Alaska. Alaska reported its warmest February in its 92-year period of record, at 6.9°C (12.4°F) higher than the 20th century average.

Why worry about wedges?

So, back to Fairbanks, or at least to the changing permafrost in this rapidly warming climate, which was on the agenda there at the Arctic Science Summit Week. (See webcast.)

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, conducted by an international team in cooperation with the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (no wonder we prefer to call them AWI), indicates that ice wedges in permafrost throughout the Arctic are thawing at a rapid pace. The first thought that springs to my mind is collapsing buildings, remembering seeing cooling systems in Greenland to keep the foundations of buildings in the permafrost frozen and so stable. Of course that only affects areas which are built upon (certainly bad enough). The new study looks at what the melting ice wedges will mean for the hydrology of the Arctic tundra. And that impact will be massive, the scientists say.

The ice wedges go down as far as 40 metres into the ground and have formed over hundreds or even thousands of years, through freezing and melting processes. Now the researchers have found that even very brief periods of above-average temperatures can cause rapid changes to ice wedges in the permafrost near the surface. In nine out of the ten areas studied, they found that ice wedges thawed near the surface, and that the ground subsided as a result. So, once more, humankind is changing what nature created over thousands of years in a very short space of time. I am reminded of a recent study indicating that our greenhouse gas emissions have even postponed the next ice age.

A dry future for the Arctic?

“The subsiding of the ground changes the ground’s water flow pattern and thus the entire water balance”, says Julia Boike from AWI, who was involved in the study. “In particular, runoff increases, which means that water from the snowmelt in the spring, for example, is not absorbed by small polygon ponds in the tundra but rather is rapidly flowing towards streams and larger rivers via the newly developing hydrological networks along thawing ice wedges”. The experts produced models which suggest the Arctic will lose many of its lakes and wetland areas if the permafrost retreats.

Co-author Guido Grosse, also from AWI, says the thaw is much more significant that it might first appear. The changes to the flow pattern also change the biochemical processes which depend on ground moisture saturation, he says.

The permafrost contains huge amounts of frozen carbon from dead plant matter. When the temperature rises and the permafrost thaws, microorganisms become active and break down the previously trapped carbon. This in turn produces the greenhouse gases methane and carbon dioxide. This is a topic already well researched, at least with regard to slow and steady temperature rises and thawing of near-surface permafrost, the authors say. But the thawing of these deep ice wedges will lead to massive local changes in patterns. “The future carbon balance in the permafrost regions depends on whether it will get wetter or dryer. While we are able to predict rainfall and temperature, the moisture state of the land surface and the way the microbes decompose the soil carbon also depends on how much water drains off”, says Julia Boike.

Now the results of the research have to be integrated into large-scale models.

The study of the impacts of thawing ice wedges seems to me like a good metaphor for the relation between Arctic climate change and what’s happening to the planet as a whole. Something changes in a localised area, which turns out to have far greater significance for a much wider area of the planet (or even the whole).

Arctic winter: warm, wet, weird

Here in Germany, the winter has seemed strange enough. We had flowers in bloom at Christmas, and people sneezing with pollen allergies. Overall it was extremely mild. Now we are just having the odd flurry of sleet, with the magnolias getting ready to bloom and much of nature said to be three weeks ahead of schedule. But that is nothing compared to what’s been going on in the Arctic.

“The Old Normal is Gone”, is the headline of a piece on Slate by Eric Holthaus, sub-headed “February Shatters Global Temperature Records”. He says the record warmth is so dramatic he is prepared to comment using unofficial data, before the official data comes out mid-March. February 2016, he says was probably somewhere between 1.15 and 1.4 degrees Celsius warmer than the long-term average, and about 0.2 degrees above last month, which was itself a record-breaker. This, Holthaus calculates, means while it took us from the start of industrialization until last October to reach the first 1 degree C. of warming, we have now gone up an extra 0.4 degrees in just five months. Paris target 1.5 degrees maximum – here we come!

In the Arctic, this is particularly dramatic. Parts of the Arctic were more than 16 degrees Celsius warmer than “normal” for the month of February, which, Holthaus says, is more like June temperatures, although it would normally be the coldest month.

Svalbard, one of my favourite icy places, has averaged 10 degrees Celsius above normal this winter, with temperatures rising above the freezing mark on nearly two dozen days since December first.

Correspondingly, the Arctic sea ice has reached a record low maximum. Lars Fischer, writing in the German publication Spektrum der Wissenschaft, notes that January already saw the smallest ice growth of the last ten years. In mid-February, he writes, satellite data showed the ice cover in some parts of the high north was almost a quarter of a million square kilometers less than ever before on this date. This lasted two weeks, than the ice grew a little last week, to draw equal with the previous all time low for a first of March. New ice will be much thinner than the old multi-year ice, a trend that has been increasing.

New satellite data

Researchers are using a new technique to gain data about the thinning ice pack in real time. An article in Nature, “Speedier Arctic data as warm winter shrinks sea ice”, describes a new tool to track changes as they happen and provide near real time estimates of ice thickness from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 satellite. Previously, there was a time lag of at least a month.

Satellite data is revolutionizing what we know about the Arctic ice. The news is not good. (Pic. I.Quaile, Tromso)

Natural fluctuation, el Nino or human-made climate change?

Of course there are those who say fluctuation is natural in the Arctic. But this year, this fluctuation is extreme. Some researchers say the melt season started a whole month too early. Certainly, at this time, the Arctic should be in the grip of winter.

Fischer titles his article “Absurd winter in the Arctic”. I’m not sure absurd is the best way of describing it. (It could actually seem quite logical if you look at the extent of extra warmth we have been creating with our greenhouse gas emissions). Looking at an article in the Independent by Geoffrey Lean, I see the term “absurdly warm”comes from the NSIDC, National Snow and Ice Data Centre in Boulder, Colorado. The “strangest ever” and “off the chart” are used by NSIDC director Mark Serreze and NOOA respectively. Those figure.

In December 2015, the high Arctic experienced a heatwave. We saw temperatures near the North Pole going above freezing point. January was the warmest month since the beginning of weather data. In February, parts of the Arctic were more than ten degrees warmer than the long-term average.

The Arctic Oscillation is partly to blame. It is currently such that warm air can make its way north. Strong Atlantic storms have been pressing the warm, moist air north into the High Arctic. But surely there can be no doubt that our human-made climate warming is playing a major role in all this?

It remains to be seen how the situation will develop as the spring sets in. Fisher notes that the last winter ice maximum extent was very low, but was not followed by a new record low in summer.

Eric Holthaus notes that although we are experiencing a record-setting El Nino, which “tends to boost global temperatures for as much as six or eight months beyond its wintertime peak”, this alone cannot be responsible for the temperature records.

He quotes scientific studies indicating that El Nino’s influence on global temperatures as a whole is likely small, and that its influence on the Arctic still isn’t well known.

“So what’s actually happening now is the liberation of nearly two decades’ worth of global warming energy that’s been stored in the oceans since the last major El Nino in 1998”, he writes.

“The old normal is gone”

Whatever the cause – this record warmth is a major event in our climate system. Holthaus quotes Peter Gleick, a climate scientist at the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California in his article title: “The old normal is gone”. “The old assumptions about what was normal are being tossed out the window”.

“We could now be right in the heart of a decade or more surge in global warming that could kick off a series of tipping points with far-reaching implications”, says Holthaus. Where have I heard this before?

Lean, in the independent, says two new studies by the Woods Hole Research Center in Massachusetts give new evidence of self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms. This is not new. How much more evidence do we need? Permafrost thaws, resulting in emissions of methane and CO2 from the soil. Melting ice means the reflective white surface is replaced by dark water, which absorbs heat.

So what are we doing about it? In interviews with experts from NGOs including Earthwatch and Germanwatch recently, various experts have been confirming my own feeling that the Paris Climate Agreement may have been a milestone, but not necessarily a turning point – unless climate action is taken very quickly.

I would like to be optimistic. But there is so much evidence suggesting that whatever we do, it is likely to come too late to save the Arctic as we know – knew – it for coming generations. Come on world, prove me wrong! Please!

Feedback