New Zealand glaciers on the retreat

During my first trip to Australia around 25 years ago, I was standing outside a phone box (there are still such things even in this smartphone age) one evening, in a chilly wind.

“That wind’s coming straight up off the pole”, a local told me. Up off the pole? That was a weird image for a visitor from the northern hemisphere. It figures, the wind blows up rather than down from the pole when you’re at the other end of the world.

A few years later, during a visit to New Zealand, I was tickled to find there were “alps” to visit, with glaciers, reminiscent of some of my favourite hiking territory in Switzerland. I haven’t heard much about them since.

There hasn’t been much about New Zealand in the media here in Europe, except when earthquakes strike, or – the latest popular summertime story – the decision to exterminate all “alien” predators like mice, rats and possums.

But this week I came across a story by the New Zealand Herald on Twitter, entitled “warning sounds for vanishing glaciers”. Needless to say this set the alarm bells ringing with the Iceblogger.

It seems these beautiful icy regions have also been affected considerably by climate warming.

Rapid retreat

The South Island of New Zealand is home to snowy mountains and picturesque glaciers. The article by Jamie Morton describes how the glaciers have been retreating massively since 2011. The pictures, taken by Brian Anderson of Victoria University’s Antarctic Research Centre, show a dramatic change. The latest measurements for Fox Glacier and Franz Josef Glacier, the ones I visited, show they have “shrunk to record levels”, the article quotes Dr. Anderson.

I must delve into my photo archive at home for pics taken when I was there in 2000 and compare them with the latest. I have the feeling the comparison would be a sobering one.

Twice a year, scientists conduct surveys of the snowlines and glacier retreats in New Zealand’s Southern Alps. The measurements take place at the end of winter, and again at the end of summer.

The scientist says the snow accumulation on the glaciers was average in winter 2015, but high by the end of the very warm summer in 2016.

In the last five years, it seems the Fox Glacier has retreated 750 meters, the Franz Josef as much as 1.5 kilometres.

The ice volume in the Southern Alps has decreased from 170 cu km in the 1890s to a current 36.1, and is predicted to go down to between 7 and 12 cu km, by 2100. Yikes.

The last dramatic loss of ice was during the summer of 2010/2011, under the influence of a strong La Nina climate system – one of the strongest ever recorded, according to Jamie Morton. The latest ice loss appears to be similar in amount.

“Based on regional warming projections of 1.5C to 2.5 C, it has been projected by glaciologists Valentina Radic and Regine Hock that just 7 to 12 cu km of ice would remain on the alps by the end of this century, Morton writes.

The snowline has also moved up to “exceptionally high levels”, Morton quotes Dr. Andrew Lorry from the National Institute of Water and Atmosphere (NIWA).

Warming water, melting ice

The article says before last summer, the experts expected the El Nino to have a major impact. But instead, it was unseasonably warm sea surface temperatures in the Tasman Sea, bringing warmer air over land, that caused the damage.

With temperatures higher than average so far this season, it seems likely more ice and snow will be melting.

Are we surprised by all this? Perhaps not. Concerned? Saddened? Definitely. Clearly the cold wind blowing up off the south pole, like the one blowing down from the north, is no longer enough to secure those icy areas of New Zealand.

Of course emissions reductions have to take place across the board. Local melting is not only caused by local actions. Still, countries who profit from their ice and snow, like New Zealand, where the alps are an important tourist attraction, can be expected to set a good example in implementing measures to halt the warming. The “Climate action tracker”, an independent science-based assessment of country’s emissions targets and actual action, rates New Zealand’s INDC 2030 target as “inadequate”. That means its commitment is not in line with a “fair” approach to reach a 2° C maximum temperature rise pathway.

“If most other countries followed the New Zealand approach, global warming would exceed 3–4°C”, the website says.

Maybe I better not wait too long for another visit to those New Zealand glaciers. At this rate, I will hardly even need my snow boots.

Redundant? (Pic: I.Quaile)

Why Brexit bodes ill for the Arctic

EU headquarters in Brussels. The Arctic is high on the European Union’s foreign policy agenda. The EU Council just published new Conclusions on the Arctic (Pic: I.Quaile)

Today’s Ice Blog post was going to be about permafrost, with the the International Conference on Permafrost drawing to a close after a week in Potsdam outside Berlin today. But the Brexit decision is casting a shadow over a lot of things today – and that includes the international spirit of cooperation that is the key to successfully tackling the all-embracing challenge of climate change and its destructive impacts on Arctic ice and permafrost. And while the permafrost is melting, the political atmosphere and social climate here in Europe are definitely becoming much colder.

British breakaway bad news for science

Not that the decision in itself will necessarily have a direct, immediate impact. Scientific research will go on in Britain and other parts of the world regardless of whether or not the country is a member of the European Union. The UK has a long tradition of polar exploration and research. But research relies on international cooperation – and the EU has become one of the key funders of Arctic research in recent decades.

British Arctic marine biologist collaborating with Dutch colleagues. (Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen, Pic: I.Quaile)

Leading scientists including Stephen Hawking have said a Brexit would be a disaster for UK science in general.

A group of 13 Nobel prize-winning scientists have also warned that leaving the EU would pose a “key risk” to British science. The group, which includes Peter Higgs, who predicted the existence of the Higgs boson particle, say losing EU funding would put UK research “in jeopardy”.

“Inside the EU, Britain helps steer the biggest scientific powerhouse in the world”, the group claim in a letter to the British Daily Telegraph.

While the other side insisted leaving the EU would not be damaging, the majority of scientists appear to be in favour of Britain remaining in the EU. 83% of scientists polled opposed Brexit.

International “give-and-take”

It is not just a matter of EU funding for British science. The scientist group stressed that British scientists should also be involved in the EU as a hub of innovation and research. They say more than one in five of the world’s researchers move freely within the EU boundaries.

Restricting this free movement is one of the key aims of the Brexit campaign. As a British journalist working in Germany, I have experienced the benefits of being able to travel, study and work in other European countries for many years.

Future generations bear the brunt

The majority of young people who voted apparently voted to stay in the EU. This is the generation that stands to gain or lose by the Brexit decision. If I think of all the dedicated young scientists from Britain and other countries I have interviewed over the years, working across borders on issues that are certainly not limited to one local area, it makes me sad and even angry that they stand to lose out because of a campaign that was based on negative sentiments like the desire to keep foreign workers and refugees out of Britain, or vague and unfounded claims that everything that does not work in Britain is the fault of the EU. No, it’s not perfect, but I doubt that many of the arrangements that protect nature in the UK and other European countries would be in place without the involvement of Brussels. And how is a body like the EU going to change and reform if not through pressure from within?

Anyone who cares about the environment knows that without international cooperation, it is not possible to protect our air, land, water and atmosphere against abuse and pollution.

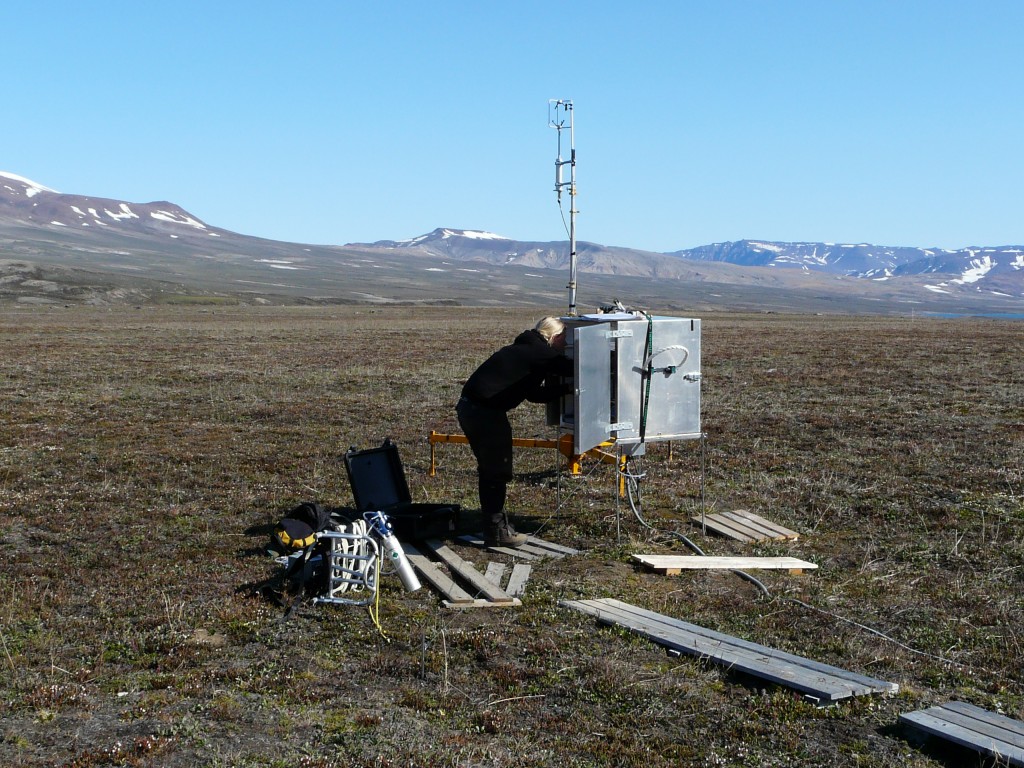

Measuring CO2 emissions from summer permafrost at Zackenberg, Greenland. GLobal emissions warm the Arctic, melting permafrost reinforces the global warming effect. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Not just about money

In an article for the MIT Technology Review, Debora MacKenzie says the EU budgeted 74.8 billion euros for research from 2014 to 2020. Brexiters, she writes, say British taxpayers should simply keep their contribution and spend it at home:

“They’d take a serious loss if they did. Britain punches above its weight in research, generating 16 percent of top-impact papers worldwide, so its grant applications are well received in Brussels. Between 2007 and 2013, it paid 5.4 billion euros into the EU research budget but got 8.8 billion euros back in grants. British labs depend on that for a quarter of public research funds, a share that has increased in recent years. A cut in that funding after Brexit could drag down every field in which British research is prominent—which is most of them.”

MacKenzie also quotes Mike Galsworthy, a health-care researcher at University College London who launched the social-media campaign Scientists for EU:

“It’s not just funding, EU support catalyzes international collaboration.” Galsworthy puts his finger on a key issue here:

“The EU funds research partly to boost European integration: for most programs you need collaborators in other EU countries to get a grant. This isn’t a bad thing, as collaborative work tends to mean more and higher-impact publications.”

Indeed.

International team measure ocean acidification off Spitsbergen, as part of EU EPOCA programme. (Pic.: I.Quaile)

One shared world

The spirit behind the vote to leave the EU is to a large extent based on nationalism and xenophobia. If it were to prevail, it would lead us backwards and result in fragmentation. That has to be bad news for those of us who believe in working together across borders for the greater good of the planet as a whole. Climate warming is a global phenomenon. We need to work together to tackle it. The icy regions of the northern hemisphere may belong geographically to individual countries like the USA, Canada, Russia or Norway. But in today’s industrialized, globalised world, no single player alone can stop the ice from melting. Or regulate the increased fishing, shipping or exploitation of natural resources in once pristine areas now becoming rapidly accessible.

Arctic sea ice, Greenland and Europe’s weird weather

As I write this, I am sitting in a short-sleeved shirt with the window open, enjoying an unusually warm start to the month of May. It’s around 27 degrees Celsius in this part of Germany, pleasant, but somewhat unusual at this time. The first four months of this year have been the hottest of any year on record, according to satellite data.

The Arctic is not the first place people tend to think of when it comes to explaining weather that is warmer – as opposed to colder – than usual in other parts of the globe. But several recent studies have increased the evidence that what is happening in the far North is playing a key role in creating unusual weather patterns further south – and that includes heat, at times.

Why sea ice matters

The Arctic has been known for a long time to be warming at least twice as fast as the earth as a whole. As discussed here on the Ice Blog, the past winter was a record one for the Arctic, including its sea ice. The winter sea ice cover reached a record low. Some scientists say the prerequisites are in place for 2016 to see the lowest sea ice extent ever.

Several recent studies have increased the evidence that these variations in the Arctic sea ice cover are strongly linked to the accelerating loss of Greenland’s land ice, and to extreme weather in North America an Europe.

“Has Arctic Sea Ice Loss Contributed to Increased Surface Melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet”, by Liu, Francis et.al, published in the journal of the American Meteorological Society, comes to the conclusion: “Reduced summer sea ice favors stronger and more frequent occurrences of blocking-high pressure events over Greenland.” The thesis is that the lack of summer sea ice (and resulting warming of the ocean, as the white cover which insulates it and reflects heat back into space disappears and is replaced by a darker surface that absorbs more heat) increases occurrences of high pressure systems which get “ stuck and act like a brick wall, “blocking” the weather from changing”, as Joe Romm puts it in an article on “Climate Progress”.

Everything is connected

The study abstract says the researchers found “a positive feedback between the variability in the extent of summer Arctic sea ice and melt area of the summer Greenland ice sheet, which affects the Greenland ice sheet mass balance”. As Romm sums it up:“that’s why we have been seeing both more blocking events over Greenland and faster ice melt.”

He quotes co-author Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University, New Jersey, explaining how these “blocks” can lead to additional surface melt on the Greenland ice sheet, as well as “persistent weather patterns both upstream (North America) and downstream (Europe) of the block.

“Persistent weather can result in extreme events, such as prolonged heat waves, flooding, and droughts, all of which have repeatedly reared their heads more frequently in recent years”, Romm concludes.

“Greenland melt linked to weird weather in Europe and USA” is the headline of an article by Catherine Jex in Science Nordic. People are usually interested in changes in the Greenland ice sheet because of its importance for global sea level, which could rise by around seven metres if it were to melt completely. But Jex also draws attention to the significance of changes to the Greenland ice for the Earth’s climate system as a whole.

The jet stream

“Some scientists think that we are already witnessing the effects of a warmer Arctic by way of changes to the polar jet stream. While an ice-free Arctic Ocean could have big impacts to weather throughout the US and Europe by the end of this century”.

She also notes some scientists warning of “superstorms”, if melt water from Greenland were eventually to shut down ocean circulation in the North Atlantic.

The site contains an interactive map to indicate how changes in Greenland and the Arctic could be driving changes in global climate and environment.

The jet streams drive weather systems in a west-east direction in the northern hemisphere. They are influenced by the difference in temperature between cold Arctic air and warmer mid-latitudes. With the Arctic warming faster than the rest of the planet, this temperature contrast is shrinking, and scientists say the jet streams are weakening.

Jex quotes meteorologist Michael Tjernström, from Stockholm University, Sweden: “Climatology of the last five years shows that the jet has weakened,” says. Its effect on weather around the world is a hot topic.

“We’ve had strange weather for a couple of years. But it’s difficult to say exactly why.”

One explanation, Jex writes, is that a weak jet stream meanders in great loops, which can bring extremes in either cold dry polar air or warmer wetter air from the south, depending on which side of the loop you find yourself. If the jet stream gets “stuck” in this kind of configuration, these extreme conditions can persist for days or even weeks.

Experts have attributed extreme events like the record cold on the east coast of the USA in early 2015, a record warm winter later the same year, and the summer heat waves and mild wet winters with exceptional flooding in the UK to these kind of “kinks” in the jet stream.

Greenland and the ocean

The changes to Greenland’s vast land ice sheet also have consequences for ocean circulation, because they mean an influx of the cold fresh water flowing into the salty sea. And the sea off the east coast of Greenland plays a key role in the movement of water, transporting heat to different parts of the world’s oceans and influencing atmospheric circulation and weather systems.

There have often been “catastrophe scenarios” suggesting the Gulf Steam, which brings warm water and weather from the tropics to the USA and Europe could ultimately be halted, leading to a new ice age. (Remember the “Day after Tomorrow?)

Although this extreme scenario is currently considered unlikely, research does suggest that the major influx of fresh water from melting ice in Greenland and other parts of the Arctic could slow the circulation and result in cooler temperatures in north western Europe.

Jex goes into the theory of a “cold blob” of ocean just south of Greenland, where melt water from the ice sheet accumulates. Some scientists say this indicates that ocean circulation is already slowing down. The “blob” appeared in global temperature maps in 2014. While the rest of the world saw record breaking warm temperatures, this patch of ocean remained unusually cold.

According to a recent study led by James Hansen, from Columbia University, USA, the ‘cold blob’ could become a permanent feature of the North Atlantic by the middle of this century. Hansen and his colleagues claim that a persistent ‘cold blob’ and a full shut down of North Atlantic Ocean circulation could lead to so-called ‘superstorms’ throughout the Atlantic. And there is geological evidence that this has happened before, they say. But the paper was controversial and many climate scientists questioned the strength of the evidence.

However, some scientists already attribute western Europe’s warm and wet winter of 2015 to the “cold blob”, Jex notes, which may have altered the strength and direction of storms via the jet stream.

The good old British weather

The UK’s Independent goes into a new study by researchers at Sheffield University, which indicates soaring temperatures in Greenland are causing storms and floods in Britain. The Independent’s author Ian Johnston says the study “provides further evidence climate change is already happening”.

It never ceases to amaze me that evidence is still being sought for that, but, clearly, there are still those who are yet to be convinced our human behavior is changing the world’s climate. So every bit of scientific evidence helps – especially if it relates to that all-time favourite topic of the weather.

The study also looks at the static areas of high pressure blocking the jet stream. With amazing temperature rises of up to ten degrees Celsius during winter on the west coast of Greenland in just two decades, it is not hard to imagine how this can effect the jet stream, and so our weather in the northern hemisphere.” If forced to go south, the jet stream picks up warm and wet air – and Britain can expect heavy rain and flooding. If forced north, the UK is likely to be hit by cold air from the Arctic”, Johnston writes.

The article quotes Professor Edward Hanna from the University of Sheffield, lead author of a paper about the research published in the International Journal of Climatology, and says seven of the strongest 11 blocking effects in the last 165 years had taken place since 2007, resulting in unusually wet weather in the UK in the summers of 2007 and 2012.

Hanna told the Independent computer models used 10 to 15 years ago to predict the extent of sea ice in the Arctic had significantly underestimated how quickly the region would warm.

“It’s very interesting to look at the observed changes in the Arctic … the actual observations are showing far more dramatic changes than the computer models,” Professor Hanna said.

“You do get sudden starts and jumps. It’s the sudden changes that can take us by surprise and there certainly does seem to have been an increase in extreme weather in certain places.”

Drawing conclusions (or not?)

In the Washington Post, (reprinted on Alaska Dispatch News) Chelsea Harvey sums up the conclusions of the latest research in an article entitled “Dominoes fall: Vanishing Arctic ice shifts jet stream, which melts Greenland glaciers”:

“There are a more complex set of variables affecting the ice sheet than experts had imagined. A recent set of scientific papers have proposed a critical connection between sharp declines in Arctic sea ice and changes in the atmosphere, which they say are not only affecting ice melt in Greenland, but also weather patterns all over the North Atlantic”.

So what do we learn from all of this? Sometimes I ask myself how many times we have to hear a message before we really take it in and decide to do something about it.

Here in Bonn, not far from the office where I am sitting now, the first round of UN climate talks since the Paris Agreement at the end of last year will be kicking off this coming weekend. The aim is to stop the rise in global temperature from going about two, preferably 1.5 degrees C. We have already passed the one degree mark. In an interview with the Guardian this week, the head of the IPCC Hoesung Lee says it is still possible to keep below two degrees, although the costs could be “phenomenal”. But many scientists and other experts are increasingly dubious about whether emissions can really peak in time to achieve the goal. Current commitments by countries to emissions reductions still leave us on the track for three degrees at least.

The concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is, as the Guardian puts it, “teetering on the brink of no return”, which the landmark 400 ppm measured for the first time at the Australian station at Cape Grim and unlikely to go below the mark again at the Mauna Loa station in Hawaii.

On my desk, I have a book entitled “Arctic Tipping Points”, by Carlos M. Duarte and Paul Wassmann. It was published in 2011. Before that, Professor Duarte had explained the global significance of what is happening in the Arctic to me

at an Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromso, Norway. How much more evidence do we need? Science takes a long time to research, evaluate and publish solid evidence of change and its consequences, with complex review processes. If politicians delay much longer, the pace of climate change will be so fast that action to avert the worst cannot keep up. Meanwhile, that Arctic ice keeps dwindling – and I sense another major storm on the approach.

Earth Day, Climate pact signing – and the Arctic?

How are you feeling this Earth Day? In some ways it could mark a turning point for the planet, with some 165 countries signing the Paris climate treaty at UN headquarters in New York. But, as, always, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. And so far, I’m not sure it is quite tasty enough.

The trouble is, signing agreements alone is not enough. They have to be turned into action. The world is heating up way too fast, and the transition to an emissions-free world is far too slow. Yes, we can do it, I am convinced. But as well as the political will to sign an agreement, we need the political will to implement measures which will be unpopular with businesses and consumers because they mean major changes to how we work, trade and live.

In the meantime, the Arctic is facing a decline in sea ice that could equal or even beat the negative record of 2012.

Sea ice physicists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), have evaluated current satellite data on the thickness of the ice cover. The data show that the Arctic sea ice was already extraordinarily thin in the summer of 2015 and comparably little new ice formed during the past winter. Speaking at the annual General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna, AWI sea ice physicist Marcel Nicolaus said data collected by the CryoSat-2 satellite revealed large amounts of thin ice that are unlikely to survive the summer.

Hard to forecast

Predicting the summer extent of the Arctic sea ice several months in advance still poses a major challenge to scientists and meteorologists. Between now and the end of the melting season, the fate of the ice will ultimately be determined by the wind conditions and air and water temperatures during the summer months. However, conditions during the preceding winter lay the foundations.The AWI scientists say this spring, conditions are as “disheartening as they were in 2012”, when the sea ice surface of the Arctic went on to reach a record low of 3.4 million square kilometres.

At the end of March, the Arctic sea ice was at a record low winter maximum extent for the second straight year, according to scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and NASA. Air temperatures over the Arctic Ocean for the months of December, January and February were 2 to 6 degrees Celsius (4 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit) above average in nearly every region.

This year’s maximum winter extent was 1.12 million square kilometers (431,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average of 15.64 million square kilometers (6.04 million square miles) and 13,000 square kilometers (5,000 square miles) below the previous lowest maximum that occurred last year.

The September Arctic minimum began drawing attention in 2005 when it first shrank to a record low extent over the period of satellite observations. It broke the record again in 2007, and then again in 2012. The March Arctic maximum tended to attract less attention until last year, when it was the lowest ever recorded by satellite.

Ice conditions “catastrophic”

Recently, here on the Ice Blog, I published an account by Larissa Beumer, one of a team of Arctic experts on board the Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise, which has been checking the ice conditions the Arctic archipelago of Spitsbergen. From the ship, she told me the ice conditions were “catastrophic and way outside of normal variations”. She reported transport problems, with many of the usual routes inaccessible by dog sled or snow mobile. She talked of a lack of ice in places where navigation is usually impossibly up to June or July.

Ice and open water, photographed by Nick Cobbing for Greenpeace, from the Arctic Sunrise, off Spitsbergen.

On thin ice

AWI scientist Marcel Nicolaus says new ice only formed very slowly in many regions of the Arctic, on account of the particularly warm winter.

“If we compare the ice thickness map of the previous winter with that of 2012, we can see that the current ice conditions are similar to those of the spring of 2012 – in some places, the ice is even thinner,” he told journalists at the Vienna Geosciences meeting.

Nicolaus and his colleague Stefan Hendricks evaluated the sea ice thickness measurements taken over the past five winters by the CryoSat-2 satellite for their sea ice projection. They also used data from seven autonomous snow buoys, which they placed on ice floes last autumn. These measure the thickness of the snow cover on top of the sea ice, the air temperature and air pressure. A comparison of their temperature data with AWI long-term measurements taken on Spitsbergen has shown that the temperature in the central Arctic in February 2016 exceeded average temperatures by up to 8 °Celsius.

Breaking ice record

In previously ice-rich areas like the Beaufort Gyre off the Alaskan coast or the region south of Spitsbergen, the sea ice is considerably thinner now than it normally is during the spring. “While the landfast ice north of Alaska usually has a thickness of 1.5 metres, our US colleagues are currently reporting measurements of less than one metre. Such thin ice will not survive the summer sun for long,” Stefan Hendricks said.

The scientists say all the available evidence suggests that the overall volume of the Arctic sea ice will be decreasing considerably over the course of the coming summer. They suspect the extent of the ice loss could be great enough to undo all growth recorded over the relatively cold winters of 2013 and 2014. “If the weather conditions turn out to be unfavourable, we might even be facing a new record low,” Stefan Hendricks said.

So the AWI researchers fear we are going to see a continuation of the dramatic decline of the Arctic sea ice throughout 2016. From that point of view, the signing of Paris climate pact comes way too late. UN Secretary-General Ban ki-Moon is stressing that this can only be the beginning, and that the mammoth task of decarbonising the economy still lies ahead. Here’s hoping the Paris Agreement will not just be a piece of paper which governments use to salve their consciences. Here in Germany, people are concerned that the government will not reach its ambitious climate targets at the present pace. Given that this country has already made remarkable progress in the transition to renewable energy for its electricity production, that is a worrying trend. And other major emitters still have even more to do if that two degree, let alone the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit to global warming is to be more than a very hot piece of pie in the steadily warming sky.

Rising seas culprit: ice or heat?

My attention was caught this week by a study that ascertained that thermal expansion accounts for a much greater share of sea level rise than previously thought. In fact, quite a few journalists got the message wrong. They thought the researchers had found that climate change was causing sea level rise twice as high as previously thought, which would have been quite a sensation. In fact, what the scientists actually found was that the amount of sea level rise that comes from the oceans warming and expanding has been underestimated and is probably about twice as much as previously calculated. There is a clear difference, which does not make the research – using the latest available satellite data – any less interesting.

Since two of the authors of the study are based here in Bonn, I was able to drop in on them and get them to explain their findings and the implications for our Living Planet programme. That will be broadcast in the near future. I also talked to Professor Anders Levermann from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research on the phone, to get the research findings into context.

While physicists understand the workings of thermal expansion in the oceans in general, Levermann told me there is still a lot to learn about how the heat from excess warming is transported in the ocean, which is of key importance to understanding sea level rise, amongst other things. He says the new research will help make models of future sea level rise more accurate.

The Bonn researchers explained to me how satellite technology has made huge improvements in the collection of data, especially relating to the very deep areas of the ocean, which are very difficult to reach with conventional measuring gauges. Professor Kusche told me he would like to see the results of the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, being used by governments and coastal planners, as sea level rise will affect a large number of people living in coastal areas in the not-too-distant future. Warming seas are also linked to the occurence of storms, making the findings doubly relevant to those involved in protecting coastal areas.

From an Iceblogger point of view, I was keen to know whether the knowledge about the amount of sea level rise ascribed to thermal expansion had any implications for the role played by melting ice in raising sea level. If thermal expansion is accounting for a higher share of the sea level rise, is melting ice from Greenland and Antarctica accounting for less? I put that question first to Professor Kusche.

“We think that less of the sea level rise is coming from melting ice and glaciers, that’s actually true,” he answered. He said he and his colleagues had done a very thorough re-analysis of all the measurements available over the last 12 or 13 years, “and we are pretty sure that our numbers are correct”.

Rietbroek came in that that point: “Less, but not that much less. If you look at pubished literature and estimates of glacier melting, and try to add those up, you won’t be that far away from what we get. So the melting of glaciers is not that different from what’s been found previously”, he added.

I put the same question to Professor Levermann from PIK, who runs an ice sheet model for the Antarctic and was lead author of the IPCC chapter on sea level change. He explained to me that the various contributions to sea level rise are measured and modelled separately by different teams of experts in particular fields. The models all have a wide range of possible variation. He told me there is still some uncertainty in the distribution of the “sea level rise budget” between thermal expansion, ice sheet melt, mountain glacier melt and groundwater mining. While the latest findings on thermal expansion could potentially shift the relative contributions and are important for improving models to project future sea level rise more accurately, they do not change the validity of predictions relating to the amount of ice going into the ocean.

Ultimately, Levermann says, one of the IPCC statements with the highest certainty is that sea level will continue to rise for centuries to come. He was one of the authors of yet another study published in Nature Climate Change this past week, led by Peter Clark from the Oregon State University. It affirms that our greenhouse gas emissions today produce climate change commitments for many centuries to millenia. Unless the Paris climate agreement is put into practice asap and we reach zero or negative emissions, up to 20 percent of the world’s population will find itself living in areas that may have to be abandoned.

We are, indeed, living in the Anthropocene. Recently, I interviewed a scientist who found that we have already postponed the next ice age by 50,000 years through our fossil fuel emissions. The latest sea level study indicates that the next few decades offer a brief window of opportunity to avoid increased ice loss from Antarctica and “large-scale and potentially catastrophic climate change that will extend longer than the entire history of human civilization thus far”.

Feedback