Search Results for Tag: UN talks

Arctic Council – 20 years in a warming world

When Norwegian polar explorer Helmer Hanssen travelled in the early 20th century, the Arctic was a very different place. Statue in Tromso, close by Arctic Council headquarters. (I.Quaile)

20 years does not really seem like a long time. But when it comes to climate change in the Arctic, the last 20 years have brought more change than centuries gone by.

After the warmest winter in the Arctic since records began, the sea ice has declined to its second-lowest level ever. And the “second-lowest” tends to divert attention from the fact that the sea ice cover has dwindled to nearly 2.56m sq km less than the 1979 to 2000 average. That’s the size of Alaska and Texas combined.

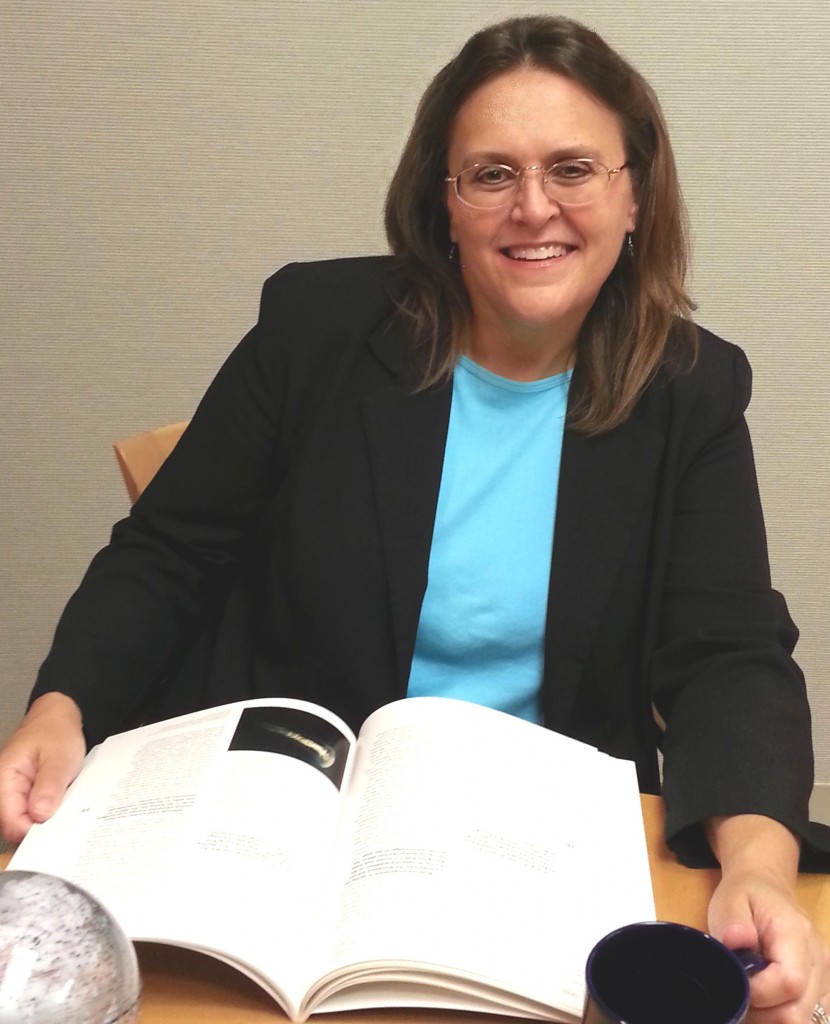

Julia Gourley, US Senior Arctic Official, has a background in environment policy. (Courtesy Arctic Council)

So the Arctic Council is celebrating its twentieth birthday at a time when concern over the impacts of planetary warming on the high north could hardly be greater.

I had the chance to interview Julia Gourley, the US Senior Arctic Official on the telephone ahead of the birthday. The US, of course, currently holds the two-year chairmanship of the body. I asked her how the Council had changed over the past 20 years.

“In the early days the Arctic state focused almost exclusively on environmental protection and science issues. But over the 20 years the countries have shifted the focus a bit. Certainly we still spend a lot of time trying to understand the environmental change that’s been going on. We spend much more time now on sustainable development issues, which in the Council generally refer to issues that affect the people of the Arctic, in particular the indigenous people. We’ve learned a lot in 20 years about the people who live there and the challenges they face.”

And those challenges are increasing all the time, especially because of the rapid pace of climate change.

Melting ice, easier access

The increase in human activity, as remote Arctic regions become more easily accessible has turned protecting the region into a whole new ball game. Gourley cites cruise ships, offshore oil and gas development , fishing and shipping as issues which have moved up the agenda.

Clearly, this means more work for the Arctic Council – and has also brought a lot more global interest in the region:

“We have 32 observer entities now, 12 of whom are countries. There are many more in the queue that are seeking observer status. What happens in the Arctic affects the entire planet, so countries all over the world are becoming interested in the region”.

With a big player like China taking a huge interest in the Arctic and looking to establish ports and secure its own access to the region, and political tensions between some of the Council members, such as Russia and the EU or the USA itself, the shadow of conflict always seem to be lurking in the background. Gourley is keen to play this aspect down. She stresses the key role of the Council in keeping the Arctic peaceful and encouraging cooperation. The USA, she says, welcomes the increasing interest by non-Arctic states – although, she adds, each of the Arctic states has their own views on that.

“We feel like we have a lot to learn as a group of Arctic states still about how the Arctic affects the rest of the world, and the more countries that are in the room listening to the discussion and learning from it and can contribute to it, the better. So we encourage non-Arctic countries that have particular expertise, to contribute to the work of the council – the scientific work, the technical work, economic work.”

Shared responsibilities

When it comes to regulating activities in the Arctic, the Council itself is not a regulatory body, but it contributes expertise to others.

“When it comes to shipping, the International Maritime Organisation is the regulatory authority all over the planet. But the Council has a strong interest in shipping in the Arctic, and so the Council has done some seminal work on the Arctic shipping situation, including a very important piece of work in 2009 called the Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment. That was the first time anyone in the world had looked deeply into the state of shipping in the Arctic in the face of climate change and reducing sea ice. That study is still cited today”.

When it comes to regulating offshore activities like mining and fishing, the Arctic states also have their own regulatory regimes, “ so it’s sort of a mix of regulatory activity by lots of different entities”, Gourley explains.

The US Arctic representative is bound, of course, to take up a diplomatic stance. But while she stresses the Council’s efforts to keep tensions low and foster cooperation rather than conflict, she does make one qualification:

“The tensions in other parts of the world haven’t affected the work of the Council. That said, of course we all have our own national views about a lot of the issues that face the Arctic. But as to working together as a group of eight countries, together with the observer states and NGOs, it really has worked quite well. We’ve managed to carve out a space that we can work in collaboratively. Now, that doesn’t mean that will always be the case. As things change in certain parts of the world it’s not easy to predict what could happen in the Arctic. But at least up to this point, we’ve been able to work together quite well.”

Balancing act

Presumably, with climate change having such a strong and rapid impact on the Arctic, there are bound to be increasing differences of opinion when it comes to striking a balance between preserving the Arctic as it is on the one hand, and on the other developing commercial and industrial activities. The US representative was quite realistic on this one:

“Yes, that’s a real tension. I think that chapter of the Arctic story is still being written. Each Arctic state comes at those questions in their own waters and their own exclusive economic zones differently, and each country’s regime is slightly different. So it’s hard to say there’s a single answer to how we resolve those questions. But it is something that is very real. It’s of concern in particular to a lot of Arctic indignous people, who want to live traditionally but also realize that modernity is moving into their world and in some cases economic development is very necessary to create good jobs and include living conditions. So it is a very real, very alive debate.”

Indeed. The Arctic conundrum in a nutshell.

Arctiv development means jobs for the next generation. But can the fragile environment cope? (I.Quaile)

Tackling black carbon

What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic – and pollution produced in the rest of the world doesn’t stay out of the Arctic.

While the UN has its own body tasked with combating climate change, there are other climate-forcing agents which affect the Arctic particularly strongly, such as black carbon or soot. The Arctic Council sees this as an area where it has a key role to play:

“Black carbon itself is not part of the UNFCCC, so it’s not part of any global regulatory regime. So we are working in the Council on ways to reduce black carbon emissions voluntarily. So I think that’s going to have some very positive results.”

At the end of our talk, I wanted to know whether optimism outweighed concern or vice versa when it comes to the future of the Arctic in our warming world. The answer didn’t surprise me. But the underlying sentiment that in spite of all the tension in the world and the feeling that climate change is gathering momentum and happening ever faster, we all have to pull together, is a message I can subscribe to:

“I think I feel optimistic in a way. Certainly, the melting that’s happening in the Arctic is potentially hugely problematic for the world. I think the science is pretty clear on that front. And it’s not going to change overnight. Even if the Paris Agreement is fully implemented right away, it’s a long time before the Arctic environment can stabilize. But when we have countries working together, if we can keep the conversation going, and we can encourage all of us in the Arctic and Arctic observer states, to work together to keep the conversation going, even if it’s slow, and to keep communication lines working, I think we do have room to be optimistic about that area of the world.”

The next 20 years are not likely to be less challenging than the last for the Arctic Council. On the contrary. You have your work cut out for you. Good luck – and happy birthday.

China, USA climate pledge – all talk, no action?

Arctic interest: China maintains a research station in Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen (Pic: I.Quaile)

In a blog post earlier this year, I mused on the danger of everybody sitting back saying, “Yes, we did”, while the planet continues to break all temperature records and fossil fuel emissions continue to rise, now that all the hype surrounding the Paris Climate Agreement in December has worn off. Back to business as usual?

It’s now September and China and the USA have made the headlines telling us they are ratifying the agreements. Of course nine months (since Paris) are tiny grains of sand in the giant egg-timer of planetary evolution. (Have those egg-timers themselves been consigned to the museum in our digital 21st century? Not important). But then again, we humans have “hotted up” the pace at which our climate, planet, atmosphere, ocean are changing dramatically.

Fireworks display or starting gun?

So how do I feel about the US-Chinese announcement? I wish I could say this makes me rejoice. Sure it’s a step in the right direction. And without action by these two top climate abusers, everybody else’s efforts would basically be worthless.

The agreement must be ratified by 55 parties representing 55 percent of total global emissions to enter into force. We are now at something like 25 parties and 40 percent of emissions, which gives ground for hope the agreement could enter into force by the end of the year.

But the proof, of the pudding lies, as always, in the eating.

The drivers of change

I have been convinced for some time that crippling air pollution will drive China to move away from fossil fuels.

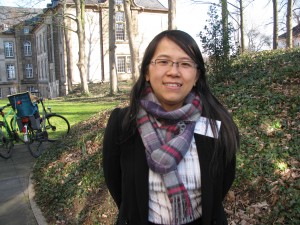

I think back on an interview I recorded with Chinese expert Lina Li from the Adelphi thinktank in Berlin, when she told me she thought China’s air pollution problem would speed up the country’s ratification and implementation of the Paris Agreement. You were right, Lina!

Lina Li from the Adelphi think-tank told me pollution concerns could speed up China’s climate action (Pic. I.Quaile)

As far as the USA is concerned, the outcome of the forthcoming election is clearly the key factor in determining how fast – or even whether – that country will move forward.

Doom and gloom?

Working on my Living Planet show for this week, I have been listening through reports on the Kuna people off the coast of Panama losing their island home to the waves, and how people in northwestern Kenya are starving because of changed rain patterns.

Forest fires, communities getting ready to “abandon home”, more extreme storms and flooding – these are all becoming so commonplace they are threatening to lose “news value”.

The CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is still climbing steadily. The global temperature is already one degree Celsius higher than it was at the onset of industrialization. That means very rapid action is needed to keep it to the agreed target of limiting warming to two degrees and preferably keeping it below 1.5 degrees.

A long, long way to go

Yes, the Paris Agreement was hailed widely as a breakthrough, with all parties finally accepting the need to combat climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. But so far, the emissions reductions pledged would still take the world closer to a three-degree rise in temperature.

Earlier this year, the International Energy Agency (IEA), issued a warning that governments can only reach their climate goals if they drastically accelerate climate action and make full use of existing technologies and policies. I wish I could say I could see this happening fast.

In my programme this week, I also have an interview my colleague Sonya Diehn conducted with Luke Sussams, from the UK-based think tank “Climate Tracker Initiative”. That is the group that came up with the term “stranded assets” which, in turn, inspired the Divestment movement.

He explains how it makes sound economic sense to shift investment out of coal and oil and into renewables. He thinks the clear advantages – less pollution, no greenhouse gas emissions, lower costs – are the best arguments to convince developing countries to “leapfrog” the fossil fuels stage and get into green energy – and into decentralized, off-grid solutions in a big way.

It’s the economy, stupid?

It seems those economic arguments are what we need. He cites the case of Rockefeller divesting from EXXON only after years of trying to convince them to change their policy on climate change. First, he argues, we should try to change things from within. If that fails, divestment may be the next option.

At the risk of seeming cynical, I have long believed that money is the key to saving the climate. The transition to a low-carbon economy is underway, but it will only succeed when governments and companies – and ultimately also consumers – realize it benefits their coffers and their pockets.

The technology is there. I am very doubtful about whether we will manage to get emissions to peak in time for us to keep to the 1.5 degree target which scientists have me convinced is what we need to do.

It seems we will need to move on to take some of the carbon out of the atmosphere using technologies now being tested – but no way ripe enough for mass implementation. I remember a Guardian interview with IPCC chief scientist Hoesung Lee a couple of months ago. He says we can still keep to the two-degree target, even if emissions do not peak by 2020, as ex- UN climate chief Christina Figueres maintained.

But he warned the costs could be “phenomenal”. He believes expensive and controversial geoengineering methods may be necessary to withdraw CO2 from the atmosphere and store it.

Meanwhile, that giant cruise-ship, the Crystal Serenity, is half-way through its controversial trip via the Northwest Passage. The operator says the trip is so successful and interest is so high they will do it again next year. They are unlikely to be foiled by a sudden onset of global cooling.

In scientific circles, the alarm bells are ringing over rising emissions from melting Arctic permafrost.

Did somebody say something about feedback loops and tipping points? Or do we just carry on regardless?

Hot, hot, hotter.. can UN talks in Bonn make a difference?

After all the hype surrounding the Paris Climate Agreement in December, there is a real danger of anti-climax, of feeling self-satisfied, of sitting back saying, “Yes, we did”, while the planet continues to break all temperature records and fossil fuel emissions continue to rise.

The first four months of this year were the hottest ever recorded. Even the “ice island” of Greenland has seen temperatures spiking in April, typically a cold month. NOAA says 2016 could be off to a similar start to 2012, when the surface of the ice sheet started melting early and then experienced the most extensive melting since the start of the satellite record in 1978. We have had several reports of islands being submerged by rising seas and devastating forest fires in Canada and now Russia, which experts say will be more common as the planet warms.

Close to my office here in Bonn, Germany’s UN city, the first official working meeting of all the parties to the Paris Agreement started on Monday, going on until next Friday. I have been there, on and off, talking to people, listening in, trying to get a sense of what is happening – or not, as the case may be.

But the atmosphere in Bonn’s new World Conference Centre is definitely low-key compared with the hype surrounding the Paris Climate Conference. Yet the world climate agreement will be worthless if the countries of the world do not succeed in transmitting it into actions in the very near future.

Time to deliver

The President of the Paris COP21, French Environmenent Minister Segolene Royal, and the incoming President of COP22, which will be held in Marrakech, Morocco’s Foreign Minister Salaheddine Mezouar, have made it clear that it is time to shift the focus from negotiation to implementation and rapid action.

The challenge ahead, they say, is to “operationalize the Paris Agreement: to turn intended nationally determined contributions into public policies and investment plans for mitigation and adaptation and to deliver on our promises.”

Indeed. There is no lack of evidence to support the urgent need for faster action on climate change. An increasing number of extreme weather events are being attributed to climate change. The CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is climbing steadily and is likely to cross the critical 400 ppm mark permanently in the not-too-distant future. The global temperature is already one degree Celsius higher than it was at the onset of industrialization. That means very rapid action is needed to keep it to the agreed target of limiting warming to two degrees and preferably keeping it below 1.5 degrees.

Three degrees and more?

The Paris Agreement was hailed widely as a breakthrough, with all parties finally accepting the need to combat climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. Countries have put pledges on the table, outlining their emissions reduction targets. But so far, the reductions pledged would still take the world closer to a three-degree rise in temperature.

At the Bonn meeting, the International Energy Agency (IEA), issued a warning that governments can only reach their climate goals if they drastically accelerate climate action and make full use of existing technologies and policies.

“The ambition to peak greenhouse gas emissions very soon is anchored in the Paris agreement, but we don’t see the actions right now to make this happen”, said Takashi Hattori, Head of the IEA’s Environment and Climate Change Unit. “At the same time, there are ‘GDP-neutral’ ways and means to get emissions to peak and then fall whilst maintaining economic growth, and that’s what we need to focus on.”

GDP-neutral means that a technology or policy does not negatively impact the economic growth of a country, and can actually contribute to the growth of that country.

In Bonn, Hattori presented what the IEA calls a “bridge scenario” involving the use of five technologies and policies which it says can bridge the gap between what has been pledged by governments so far and what is required to keep the global average temperature to as low as 1.5 degrees Celsius as part of what the agency terms a “well below 2 degrees world”

The five key measures which the IEA say could achieve a peak in emissions around 2020 are energy efficiency, reducing inefficient coal, renewables investment, methane reductions and fossil-fuel subsidy reform. That sounds to me like a very sensible – and practicable set of measures. But that doesn’t mean it will be easy.

Takashi Hattori stressed that “one size does not fit all” when it comes to climate and energy policies. Different measures will be required in different parts of the world. In the Middle East, for example, the greatest potential to reduce emissions is through reducing fossil fuel subsidies, he argued, while energy efficiency would have the greatest potential in Europe and China. He recommended the “massive deployment of renewables” in India and Latin America.

Other solutions outlined include smart grids, hydrogen as fuel that can be generated with renewable sources of energy, and “smart” agriculture.

The IEA says governments should make the energy transition not only because of rising temperatures, but because of other benefits, such as a reduction of air pollution. That makes sense. People in congested cities are more worried about pollution damaging their health than about climate change, the experts say.

I am reminded of an interview I conducted recently with Chinese expert Lina Li, when she told me she thought China’s air pollution problem would speed up the country’s ratification and implementation of the Paris Agreement.

Lina Li from the Adelphi think-tank told me pollution concerns could speed up China’s climate action (Pic. I.Quaile)

The cost argument

Although many scientists are alarmed at the slow pace of emissions reductions, IPCC chief scientist Hoesung Lee told the Guardian in an interview it was still possible to keep to the two-degree target. The current UN climate chief Christina Figueres, who will hand over to Mexican Patricia Espinosa later this year, has said emissions would have to peak by 2020 if that limit is to be kept to. But Lee is keen to keep the options open, saying it would still be possible to keep to the limits if emissions peaked later. But he warned the costs could be “phenomenal”. He believes expensive and controversial geoengineering methods may be necessary to withdraw CO2 from the atmosphere and store it.

A report published this week by UNEP says the cost for assisting developing countries to adapt to climate change could reach up to 500 billion dollars annually by 2050. This is five times higher than previous estimates, the report says.

UNEP urged countries to channel more funds towards adaptation, saying the costs would rise “sharply”, even if countries succeed in limiting global temperature increase to two degrees Celsius.

I asked Mattias Söderberg, Co-Chair of the Climate change advisory group with the climate justice ACT alliance, how he felt about the progress of climate action and the role of the current Bonn meeting. He said the UNEP report, along with the alarming news about islands disappearing under rising seas in the Pacific, highlighted the urgent need for action. “Climate change is not a matter of tomorrow, but a crisis we need to deal with today.”

Time to ratify!

So far, 177 parties have signed the Agreement. But only 16 parties have ratified the treaty. It must be ratified by 55 parties representing 55 percent of total global emissions to enter into force. Söderberg called on wealthy, industrialized countries to move ahead with ratification:

“I am happy to see many of the poor and vulnerable countries moving fast with their ratification, and I hope other countries will follow soon. I am worried about the EU, which seems to be delayed”. Söderberg says the EU, could find itself on the sidelines, overtaken by others.

But the increasing concern over refugees and migration here in Europe could make a lot of countries look more closely at climate change, which is likely to increase the number of people having to leave their homes and look for a better life elsewhere.

“Go, world, go!”

NGO representatives stress that the Bonn talks can only help kick off the series of measures necessary to halt global climate change. Greenpeace climate policy chief Martin Kaiser told me the main work had to be done in the countries themselves, which have to work out their timetables to reach the goals agreed in Paris. That means an early transition to a fossil-free future. Kaiser called on host country Germany in particular, often cited as a model for its shift to renewable energy, to come up with a binding exit strategy for coal by 2030.

“Without an exit from coal, Germany’s signature under the Paris Agreement is worthless”, he told me.

The world’s top emitters, the USA and China, will also have to take major steps to halt climate warming. The delegates meeting in Bonn until May 26 have their work cut out for them. I have always been skeptical about the mass jubilation over the Paris Agreement. Yes, we needed it. But the proof of every pudding is in the eating. All the indications are that 2016 will be the hottest year on record, and probably by the largest margin ever. If the Paris document is to be more than a lot of pieces of paper, we will have to see things happening very soon – and definitely not just in the conference rooms of Bonn and elsewhere.

Arctic sea ice, Greenland and Europe’s weird weather

As I write this, I am sitting in a short-sleeved shirt with the window open, enjoying an unusually warm start to the month of May. It’s around 27 degrees Celsius in this part of Germany, pleasant, but somewhat unusual at this time. The first four months of this year have been the hottest of any year on record, according to satellite data.

The Arctic is not the first place people tend to think of when it comes to explaining weather that is warmer – as opposed to colder – than usual in other parts of the globe. But several recent studies have increased the evidence that what is happening in the far North is playing a key role in creating unusual weather patterns further south – and that includes heat, at times.

Why sea ice matters

The Arctic has been known for a long time to be warming at least twice as fast as the earth as a whole. As discussed here on the Ice Blog, the past winter was a record one for the Arctic, including its sea ice. The winter sea ice cover reached a record low. Some scientists say the prerequisites are in place for 2016 to see the lowest sea ice extent ever.

Several recent studies have increased the evidence that these variations in the Arctic sea ice cover are strongly linked to the accelerating loss of Greenland’s land ice, and to extreme weather in North America an Europe.

“Has Arctic Sea Ice Loss Contributed to Increased Surface Melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet”, by Liu, Francis et.al, published in the journal of the American Meteorological Society, comes to the conclusion: “Reduced summer sea ice favors stronger and more frequent occurrences of blocking-high pressure events over Greenland.” The thesis is that the lack of summer sea ice (and resulting warming of the ocean, as the white cover which insulates it and reflects heat back into space disappears and is replaced by a darker surface that absorbs more heat) increases occurrences of high pressure systems which get “ stuck and act like a brick wall, “blocking” the weather from changing”, as Joe Romm puts it in an article on “Climate Progress”.

Everything is connected

The study abstract says the researchers found “a positive feedback between the variability in the extent of summer Arctic sea ice and melt area of the summer Greenland ice sheet, which affects the Greenland ice sheet mass balance”. As Romm sums it up:“that’s why we have been seeing both more blocking events over Greenland and faster ice melt.”

He quotes co-author Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University, New Jersey, explaining how these “blocks” can lead to additional surface melt on the Greenland ice sheet, as well as “persistent weather patterns both upstream (North America) and downstream (Europe) of the block.

“Persistent weather can result in extreme events, such as prolonged heat waves, flooding, and droughts, all of which have repeatedly reared their heads more frequently in recent years”, Romm concludes.

“Greenland melt linked to weird weather in Europe and USA” is the headline of an article by Catherine Jex in Science Nordic. People are usually interested in changes in the Greenland ice sheet because of its importance for global sea level, which could rise by around seven metres if it were to melt completely. But Jex also draws attention to the significance of changes to the Greenland ice for the Earth’s climate system as a whole.

The jet stream

“Some scientists think that we are already witnessing the effects of a warmer Arctic by way of changes to the polar jet stream. While an ice-free Arctic Ocean could have big impacts to weather throughout the US and Europe by the end of this century”.

She also notes some scientists warning of “superstorms”, if melt water from Greenland were eventually to shut down ocean circulation in the North Atlantic.

The site contains an interactive map to indicate how changes in Greenland and the Arctic could be driving changes in global climate and environment.

The jet streams drive weather systems in a west-east direction in the northern hemisphere. They are influenced by the difference in temperature between cold Arctic air and warmer mid-latitudes. With the Arctic warming faster than the rest of the planet, this temperature contrast is shrinking, and scientists say the jet streams are weakening.

Jex quotes meteorologist Michael Tjernström, from Stockholm University, Sweden: “Climatology of the last five years shows that the jet has weakened,” says. Its effect on weather around the world is a hot topic.

“We’ve had strange weather for a couple of years. But it’s difficult to say exactly why.”

One explanation, Jex writes, is that a weak jet stream meanders in great loops, which can bring extremes in either cold dry polar air or warmer wetter air from the south, depending on which side of the loop you find yourself. If the jet stream gets “stuck” in this kind of configuration, these extreme conditions can persist for days or even weeks.

Experts have attributed extreme events like the record cold on the east coast of the USA in early 2015, a record warm winter later the same year, and the summer heat waves and mild wet winters with exceptional flooding in the UK to these kind of “kinks” in the jet stream.

Greenland and the ocean

The changes to Greenland’s vast land ice sheet also have consequences for ocean circulation, because they mean an influx of the cold fresh water flowing into the salty sea. And the sea off the east coast of Greenland plays a key role in the movement of water, transporting heat to different parts of the world’s oceans and influencing atmospheric circulation and weather systems.

There have often been “catastrophe scenarios” suggesting the Gulf Steam, which brings warm water and weather from the tropics to the USA and Europe could ultimately be halted, leading to a new ice age. (Remember the “Day after Tomorrow?)

Although this extreme scenario is currently considered unlikely, research does suggest that the major influx of fresh water from melting ice in Greenland and other parts of the Arctic could slow the circulation and result in cooler temperatures in north western Europe.

Jex goes into the theory of a “cold blob” of ocean just south of Greenland, where melt water from the ice sheet accumulates. Some scientists say this indicates that ocean circulation is already slowing down. The “blob” appeared in global temperature maps in 2014. While the rest of the world saw record breaking warm temperatures, this patch of ocean remained unusually cold.

According to a recent study led by James Hansen, from Columbia University, USA, the ‘cold blob’ could become a permanent feature of the North Atlantic by the middle of this century. Hansen and his colleagues claim that a persistent ‘cold blob’ and a full shut down of North Atlantic Ocean circulation could lead to so-called ‘superstorms’ throughout the Atlantic. And there is geological evidence that this has happened before, they say. But the paper was controversial and many climate scientists questioned the strength of the evidence.

However, some scientists already attribute western Europe’s warm and wet winter of 2015 to the “cold blob”, Jex notes, which may have altered the strength and direction of storms via the jet stream.

The good old British weather

The UK’s Independent goes into a new study by researchers at Sheffield University, which indicates soaring temperatures in Greenland are causing storms and floods in Britain. The Independent’s author Ian Johnston says the study “provides further evidence climate change is already happening”.

It never ceases to amaze me that evidence is still being sought for that, but, clearly, there are still those who are yet to be convinced our human behavior is changing the world’s climate. So every bit of scientific evidence helps – especially if it relates to that all-time favourite topic of the weather.

The study also looks at the static areas of high pressure blocking the jet stream. With amazing temperature rises of up to ten degrees Celsius during winter on the west coast of Greenland in just two decades, it is not hard to imagine how this can effect the jet stream, and so our weather in the northern hemisphere.” If forced to go south, the jet stream picks up warm and wet air – and Britain can expect heavy rain and flooding. If forced north, the UK is likely to be hit by cold air from the Arctic”, Johnston writes.

The article quotes Professor Edward Hanna from the University of Sheffield, lead author of a paper about the research published in the International Journal of Climatology, and says seven of the strongest 11 blocking effects in the last 165 years had taken place since 2007, resulting in unusually wet weather in the UK in the summers of 2007 and 2012.

Hanna told the Independent computer models used 10 to 15 years ago to predict the extent of sea ice in the Arctic had significantly underestimated how quickly the region would warm.

“It’s very interesting to look at the observed changes in the Arctic … the actual observations are showing far more dramatic changes than the computer models,” Professor Hanna said.

“You do get sudden starts and jumps. It’s the sudden changes that can take us by surprise and there certainly does seem to have been an increase in extreme weather in certain places.”

Drawing conclusions (or not?)

In the Washington Post, (reprinted on Alaska Dispatch News) Chelsea Harvey sums up the conclusions of the latest research in an article entitled “Dominoes fall: Vanishing Arctic ice shifts jet stream, which melts Greenland glaciers”:

“There are a more complex set of variables affecting the ice sheet than experts had imagined. A recent set of scientific papers have proposed a critical connection between sharp declines in Arctic sea ice and changes in the atmosphere, which they say are not only affecting ice melt in Greenland, but also weather patterns all over the North Atlantic”.

So what do we learn from all of this? Sometimes I ask myself how many times we have to hear a message before we really take it in and decide to do something about it.

Here in Bonn, not far from the office where I am sitting now, the first round of UN climate talks since the Paris Agreement at the end of last year will be kicking off this coming weekend. The aim is to stop the rise in global temperature from going about two, preferably 1.5 degrees C. We have already passed the one degree mark. In an interview with the Guardian this week, the head of the IPCC Hoesung Lee says it is still possible to keep below two degrees, although the costs could be “phenomenal”. But many scientists and other experts are increasingly dubious about whether emissions can really peak in time to achieve the goal. Current commitments by countries to emissions reductions still leave us on the track for three degrees at least.

The concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is, as the Guardian puts it, “teetering on the brink of no return”, which the landmark 400 ppm measured for the first time at the Australian station at Cape Grim and unlikely to go below the mark again at the Mauna Loa station in Hawaii.

On my desk, I have a book entitled “Arctic Tipping Points”, by Carlos M. Duarte and Paul Wassmann. It was published in 2011. Before that, Professor Duarte had explained the global significance of what is happening in the Arctic to me

at an Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromso, Norway. How much more evidence do we need? Science takes a long time to research, evaluate and publish solid evidence of change and its consequences, with complex review processes. If politicians delay much longer, the pace of climate change will be so fast that action to avert the worst cannot keep up. Meanwhile, that Arctic ice keeps dwindling – and I sense another major storm on the approach.

Earth Day, Climate pact signing – and the Arctic?

How are you feeling this Earth Day? In some ways it could mark a turning point for the planet, with some 165 countries signing the Paris climate treaty at UN headquarters in New York. But, as, always, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. And so far, I’m not sure it is quite tasty enough.

The trouble is, signing agreements alone is not enough. They have to be turned into action. The world is heating up way too fast, and the transition to an emissions-free world is far too slow. Yes, we can do it, I am convinced. But as well as the political will to sign an agreement, we need the political will to implement measures which will be unpopular with businesses and consumers because they mean major changes to how we work, trade and live.

In the meantime, the Arctic is facing a decline in sea ice that could equal or even beat the negative record of 2012.

Sea ice physicists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), have evaluated current satellite data on the thickness of the ice cover. The data show that the Arctic sea ice was already extraordinarily thin in the summer of 2015 and comparably little new ice formed during the past winter. Speaking at the annual General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna, AWI sea ice physicist Marcel Nicolaus said data collected by the CryoSat-2 satellite revealed large amounts of thin ice that are unlikely to survive the summer.

Hard to forecast

Predicting the summer extent of the Arctic sea ice several months in advance still poses a major challenge to scientists and meteorologists. Between now and the end of the melting season, the fate of the ice will ultimately be determined by the wind conditions and air and water temperatures during the summer months. However, conditions during the preceding winter lay the foundations.The AWI scientists say this spring, conditions are as “disheartening as they were in 2012”, when the sea ice surface of the Arctic went on to reach a record low of 3.4 million square kilometres.

At the end of March, the Arctic sea ice was at a record low winter maximum extent for the second straight year, according to scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and NASA. Air temperatures over the Arctic Ocean for the months of December, January and February were 2 to 6 degrees Celsius (4 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit) above average in nearly every region.

This year’s maximum winter extent was 1.12 million square kilometers (431,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average of 15.64 million square kilometers (6.04 million square miles) and 13,000 square kilometers (5,000 square miles) below the previous lowest maximum that occurred last year.

The September Arctic minimum began drawing attention in 2005 when it first shrank to a record low extent over the period of satellite observations. It broke the record again in 2007, and then again in 2012. The March Arctic maximum tended to attract less attention until last year, when it was the lowest ever recorded by satellite.

Ice conditions “catastrophic”

Recently, here on the Ice Blog, I published an account by Larissa Beumer, one of a team of Arctic experts on board the Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise, which has been checking the ice conditions the Arctic archipelago of Spitsbergen. From the ship, she told me the ice conditions were “catastrophic and way outside of normal variations”. She reported transport problems, with many of the usual routes inaccessible by dog sled or snow mobile. She talked of a lack of ice in places where navigation is usually impossibly up to June or July.

Ice and open water, photographed by Nick Cobbing for Greenpeace, from the Arctic Sunrise, off Spitsbergen.

On thin ice

AWI scientist Marcel Nicolaus says new ice only formed very slowly in many regions of the Arctic, on account of the particularly warm winter.

“If we compare the ice thickness map of the previous winter with that of 2012, we can see that the current ice conditions are similar to those of the spring of 2012 – in some places, the ice is even thinner,” he told journalists at the Vienna Geosciences meeting.

Nicolaus and his colleague Stefan Hendricks evaluated the sea ice thickness measurements taken over the past five winters by the CryoSat-2 satellite for their sea ice projection. They also used data from seven autonomous snow buoys, which they placed on ice floes last autumn. These measure the thickness of the snow cover on top of the sea ice, the air temperature and air pressure. A comparison of their temperature data with AWI long-term measurements taken on Spitsbergen has shown that the temperature in the central Arctic in February 2016 exceeded average temperatures by up to 8 °Celsius.

Breaking ice record

In previously ice-rich areas like the Beaufort Gyre off the Alaskan coast or the region south of Spitsbergen, the sea ice is considerably thinner now than it normally is during the spring. “While the landfast ice north of Alaska usually has a thickness of 1.5 metres, our US colleagues are currently reporting measurements of less than one metre. Such thin ice will not survive the summer sun for long,” Stefan Hendricks said.

The scientists say all the available evidence suggests that the overall volume of the Arctic sea ice will be decreasing considerably over the course of the coming summer. They suspect the extent of the ice loss could be great enough to undo all growth recorded over the relatively cold winters of 2013 and 2014. “If the weather conditions turn out to be unfavourable, we might even be facing a new record low,” Stefan Hendricks said.

So the AWI researchers fear we are going to see a continuation of the dramatic decline of the Arctic sea ice throughout 2016. From that point of view, the signing of Paris climate pact comes way too late. UN Secretary-General Ban ki-Moon is stressing that this can only be the beginning, and that the mammoth task of decarbonising the economy still lies ahead. Here’s hoping the Paris Agreement will not just be a piece of paper which governments use to salve their consciences. Here in Germany, people are concerned that the government will not reach its ambitious climate targets at the present pace. Given that this country has already made remarkable progress in the transition to renewable energy for its electricity production, that is a worrying trend. And other major emitters still have even more to do if that two degree, let alone the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit to global warming is to be more than a very hot piece of pie in the steadily warming sky.

Feedback